To my sister and number-one fan, Chlo

Contents

Thank you

To Kate Bradbury for helping me shape the idea for this book and Tom Cox for showing me the Otterton beavers. To all who inspired me at the Grant Arms Hotel in March 2018, especially Mark Cocker for his wisdom and guidance, and Louise Gray for a magical morning run with the red squirrels.

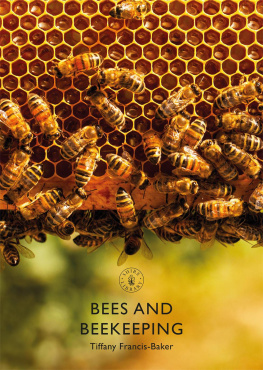

To the wonderful team at Bloomsbury who have made becoming an author so utterly enjoyable. To Jim Martin for giving me a chance, to Julie Bailey for believing in me ever since, and to Charlotte Atyeo, Hannah Paget, Hetty Touquet and the rest of the gang for all their hard work.

To all my creative, passionate friends who continue to inspire and educate me, especially Imogen Wood, Victoria Melluish, Hannah Khan, Amber Banaityte, Mark Ranger, Matt Williams, Megan Shersby, Freya Haak, Katy Livesey, Charli Sams, Emily Jochim, Hannah Rudd, and Catherine and Lizzy Ward Thomas.

To my mum and dad, Ian, Nana, Grandad, Jim and the rest of my lovely family. To Chlo, Hollie and Christie, the ultimate sisters. To my niece Meredith, brother-in-law Simon, and everyone at Butser Ancient Farm, my favourite place in the world. To Chris, Tony, Andy, Jenny, Paul, Eva, Tinks and Sparkle for welcoming me wholeheartedly into the Baker tribe. To our Spanish rescue dog Pablo for making the world even brighter.

And to Dave, my best friend.

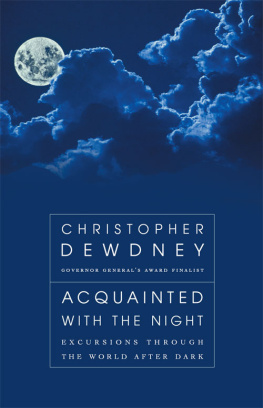

The stars are forth, the moon above the tops

Of the snow-shining mountains. Beautiful!

I linger yet with Nature, for the night

Hath been to me a more familiar face

Than that of man; and in her starry shade

Of dim and solitary loveliness,

I learnd the language of another world.

Manfred , George Gordon Lord Byron

One night in late September I happened to be on the north Norfolk coast, cocooned in duvets in the back of my car, like a lost human burrito. Id driven to Snettisham, an RSPB reserve formed of lagoons and mudflats that sprawl out to the Wash estuary and into the black North Sea. Here the stars were reflected in the water like pearlescent shoals, and the next morning I would watch waders sweep across the lagoons in the sunlight, my stomach full of blackberries foraged from the reserve paths. But tonight there was only a curlew bubbling, the sour scent of kelp and mud drifting in through the open window, and somewhere an oystercatcher peep-peeping ; with those long, orange beaks they look like Pingu mid- noot .

Two days ago my relationship had ended. After all the tea was poured, and the conversation came to its natural end, I packed a bag and drove to East Anglia. The next morning my boyfriend and his brother would be going to France on the trip we had organised together, and the thought of lingering on in Hampshire was enough to send me instead to Norfolk, a temporary distraction from the loneliness that had started to creep into my body. I kept driving until I reached the sea, found some company in a swarm of wading birds, and spent the evening watching shelducks sift for invertebrates on a shingle beach.

By midnight a waning moon hung in the sky, and I lay awake listening to waves crash down onto silted sands. Outside the birds slept and the earth continued to revolve, so indifferent to the individual creatures in its web: the ocean was alive, the stars exploding, the soil murmuring with blood flow. The earth doesnt care for relationships and heartache, only the rotation of sun and moon, the eternal movement of life and living things. Everything we do depends on the sun rising every day, but half of our lives are spent in darkness. How much energy continues to burst from the landscape after the sun goes down? And by giving in to sleep when the world grows dark, how much of life are we missing out on?

Im someone who crawls into bed each night and falls asleep within seconds. No restless hours of tedium turning over the days thoughts like a tumble dryer; I surrender wholly to sleep, and my mind falls into that euphoric chasm of the unconscious.

Or so I thought.

Like many children, my parents divorced when I was in primary school, and I gained a new stepsister, Christie, who I now love like a blood sister. We helped each other through those limbo years between infancy and adolescence when youre unsure if you want to climb trees or message boys online. The best part of gaining a new sister was sharing a room at weekends, and it was at this point in my life, having never shared a bedroom before, that I discovered I am a somniloquist: I talk in my sleep.

It was and still is, hilarious. Conversations ranged far and wide; sometimes I would shake Christie awake to tell her zombies were coming, and more than once I talked about cake. I would laugh and shout and jump up in the middle of the night, convinced that spiders were crawling around my bed. It hasnt gone away with age. New sleep mates are forewarned. At university, I once crept over to my money box on the shelf, took it down and placed it on the floor. On returning to the bed and my boyfriends puzzled expression, I replied: Burglars.

I rarely remembered anything I had said or done in the night, unless it was so dramatic that I woke myself up in the middle of it, like the time I pulled the duvet off the bed and ran into the bathroom, only to wake up where I stood, bleary-eyed and confused. When I was first told what I had been doing, it came as a genuine surprise. But it also explained one or two mysterious occurrences I remembered from my childhood, like times I had woken up in the morning at the opposite end of the bed, or when the giant teddy that lived in my toy box had inexplicably ended up squashed against my head in bed. I cant explain the feeling of shifting from the unconscious mind to the conscious one, but its incredibly disorientating and unpleasant, followed by an awkward conversation with your sleep mate who has been rudely awoken by a madwoman raving about spiders or loading the dishwasher.

After years of this behaviour I decided to see if the doctor could shed any light on my condition, and in 2015 I was referred to Papworth Respiratory Support and Sleep Centre in Cambridge, where I stayed the night under close observation. The other patients suffered from insomnia and narcolepsy, sharing weary tales of a life spent in drowsy fatigue. At night we were plugged into a machine and recorded on camera while we slept, and the next day I was eating toast and jam when my doctor arrived to ask if I thought Id been active in the night. I replied, over-confidently, that I had not, and he showed me a movement chart that looked like Jackson Pollocks latest masterpiece. I left the centre that afternoon with the advice to get more sleep and decided to accept my flaws.

What hath night to do with sleep? asked John Milton in his poem Comus , named after the Greek god of nocturnal frivolity. Since the earliest days of human civilisation, we have evolved to live our lives in daylight and hide away at night, and there are logical reasons for this: our ancestors were preoccupied with survival hunting and being hunted, gathering plants, building, socialising, farming and sleeping, all of which were entwined with the rhythms of day and night. But is it realistic to assume that of all the animals, we alone chose to sleep from dusk to dawn in undisturbed blocks? To suggest that older societies slept away the darkness and never enjoyed the midnight hour?