Archaeology of the Night

LIFE AFTER DARK IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

EDITED BY

Nancy Gonlin & April Nowell

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO

Boulder

2018 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 978-1-60732-677-9 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-678-6 (ebook)

DOI: 10.5876/9781607326786

If the tables in this publication are not displaying properly in your ereader, please contact the publisher to request PDFs of the tables.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gonlin, Nancy, editor. | Nowell, April, 1969 editor.

Title: Archaeology of the night : life after dark in ancient world / edited by Nancy Gonlin and April Nowell.

Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017018223| ISBN 9781607326779 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607326786 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: NightSocial aspects. | NightReligious aspects. | Antiquities, Prehistoric.

Classification: LCC GT3408 .A74 2017 | DDC 304.2/37dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018223

The University Press of Colorado gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the University of Victoria toward the publication of this book.

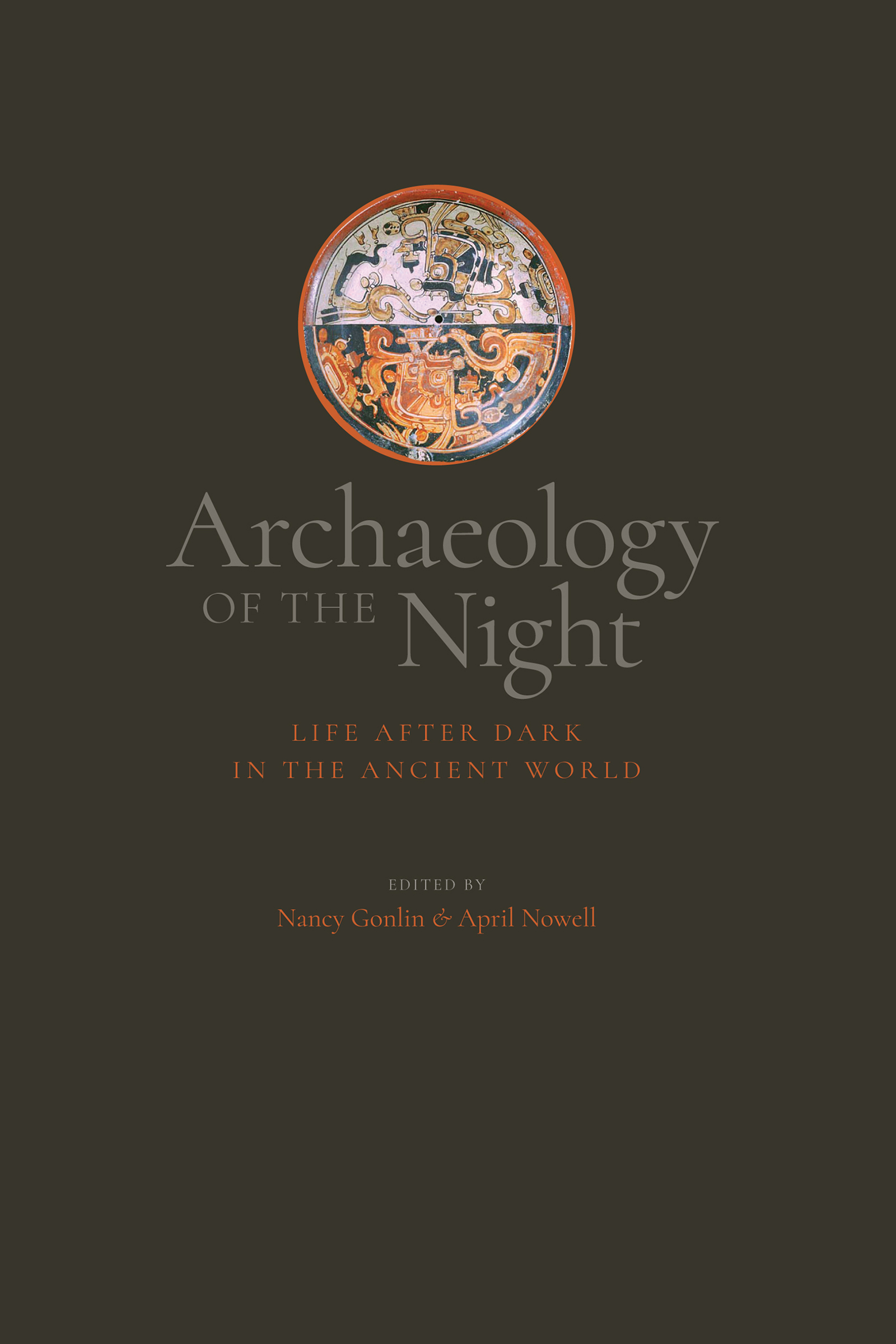

Cover photograph Justin Kerr file no. 5877

Nan : For my incredible siblingsAlice, James, Jeffrey, Robert, Thomas, Richard, and Pattiwith heartfelt appreciation and love for sharing fun-filled childhood nights, complete with monsters and moonlight

April : For Jon, Ruka, and James; and for Mom and Stephen with much love

Contents

Jerry D. Moore

Nancy Gonlin

Nancy Gonlin and April Nowell

April Nowell

Nancy Gonlin and Christine C. Dixon

Kathryn Kamp and John C. Whittaker

Minette C. Church

Alexei Vranich and Scott C. Smith

Anthony F. Aveni

Cynthia L. Van Gilder

Tom D. Dillehay

Jeremy D. Coltman

Susan M. Alt

Meghan E. Strong

Erin Halstad McGuire

Rita P. Wright and Zenobie S. Garrett

Glenn Reed Storey

Smiti Nathan

Shadreck Chirikure and Abigail Joy Moffett

Jane Eva Baxter

Margaret Conkey

Foreword

Jerry D. Moore

... and the darkness He called Night.

Genesis 1:5

The most astonishing fact about a volume on the Archaeology of the Night is that it does not already exist. Perhaps we should not be surprised. As the eighteenth-century scientist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg observed, our entire history is only the history of waking men (quoted in referred to as The Night Country. It is not a singular destination, nor are the following explorations reducible to a simple, unifying theme. Rather, the reader will discover a range of distinct inquiries, intersecting and complementary probings into what an archaeology of the night might entail.

In this foreword, I want to highlight some common themes found throughout this volume. These reflect diverse and engaging intellectual forays, ranging from the technologies of illumination, the significance of lunar and stellar observations in creating cultural landscapes, the existence of complex nocturnal ontologies, to the specific valences, transgressions, and meanings associated with darkness. Before discussing the themes explored in this volume, I want to convey to the reader what an archaeology of the night could involve by summarizing a pair of previous studies of nocturnal culture among two very different societies, the Ju/hoansi of the Kalahari (). These case studies embody many of the specific themes explored by the contributors to this volume, themes that I discuss subsequently.

Polly , 14029). On two occasions, daytime complaints escalated to threats of death with poisoned arrows, although the protagonists were restrained.

Night talk was different in tone and topic: over 80% of Ju/hoansi conversations were devoted to stories. After dinner and dark, Wiessner observes, the harsher mood of the day mellowed, and people who were in the mood gathered around single fires to talk, make music, or dance... The focus of conversation changed radically as economic matters and social gripes were put aside (, 14029).

In an equally fascinating essay regarding a very different cultural setting, Mary , 180) writes, who, by definition, renounced the superficial things of the secular world of the day, the spiritual side of night held a particular attraction. Night provided deep silence and quietude when ones thoughts could be more readily drawn to supernatural mysteries. Darkness cloaked the shared communion of prayers, including the nightly liturgical prayers, or nocturns. For example, Benedictine monks slept fully dressed in a common room lit by a single candle, rising to sing psalms within throughout the night in a darkened church (183).

The significance of the nocturns is indicated by the number of psalms sung during each nights ceremony. Documents describing monastic offices in the fifth-century report that nocturns required as many as 18 psalms to be sung on a winter night; by the sixth century this had grown to a staggering 99 psalms on Saturday and Sunday night vigils during the winter, an exhausting program in which monks slept only 57 hours (depending on the seasonal length of night) before rising around 2 a.m. to sing through the night as they spiritually prepared for the dawn. Helms observes that the office of nocturns (sometimes called vigils), [were] by far the longest and most important of the daily liturgical services, 177178). This complex nocturnal ritual involved the rejection of sin, the search for Adamic innocence, and the defeat of death. These intertwined monastic goals present early medieval monks both as creatures of the night who ritually explored the extraordinary supernatural realm manifested by darkness and as watchers for the coming day for whom the dark was the setting, the backdrop, for liturgy that anticipated its annihilation and conquest by the light (187).

I have summarized these two very different cases to give the reader some sense of the complex range of behaviors that an archaeology of night might encounter. On one hand, these two examples of nocturnal behaviors are separated by time, place, cultural traditions, and ontology, and yet there are fascinating intersections between them: the special behaviors associated with nightly practices, the change between day and night in the sounds and subjects of human voices, and the rich cultural associations with darkness and night. These two cases suggest what an archaeology of the night could illuminate, foreshadowing exciting lines of inquiry developed by the contributors to this volume.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.