About the Author

Brian Fagan, one of the worlds leading writers about archaeology, is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His many books include Cro-Magnon and Beyond the Blue Horizon, and he has written or edited for Thames & Hudson such volumes as The First North Americans, Discovery!, The Complete Ice Age and The Seventy Great Mysteries of the Ancient World.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Great Explorers

The Scientists

The Man Who Deciphered Linear B:

The Story of Michael Ventris

Breaking the Maya Code

Cracking the Egyptian Code

Cities That Shaped the Ancient World

Figuring It Out:

What Are We? Where Do We Come From?

The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

The city was desolate. No remnant of this race hangs around the ruins, with traditions handed down from father to son and from generation to generation. It lay before us like a shattered bark in the midst of the ocean, her masts gone, her name effaced, her crew perished, and none to tell whence she came, to whom she belonged.

John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Chiapas and Yucatn, 1839

Archaeology, the study of the human past through material remains, has grown over two centuries and more from a pursuit conducted by amateurs and wealthy dilettantes based almost entirely in Europe, to a global science carried out by highly trained scholars working across many subdisciplines. At the same time our knowledge has exploded of what our distant ancestors achieved and the civilizations and diverse cultures they created. We now know that humanity made the first tools not a few thousand years ago in Europe, as was once thought, but more than 2.5 million years ago in Africa. We now know that civilization was not invented in Egypt and the Near East, spreading from there to the rest of the globe, but emerged independently in six or seven locations in different parts of the world. We now know that the Maya of Mexico, the Chimu of Peru and the Khmer of Cambodia built cities and created art styles of a grandeur and sophistication unimagined by Eurocentric scholars in the 18th and early 19th centuries. How did these transformations come about? Who were the men and women who made the spectacular discoveries and unearthed the amazing treasures that adorn our museums today?

General view of Uxmal, taken from the Archway of Las Monjas by Frederick Catherwood, 1844. He and his fellow explorer John Lloyd Stephens rediscovered great Maya cities lost for a millennium. Newberry Library/SuperStock.

Louis and Mary Leakey, with their son and two dogs, inspect the campsite of an early hominin at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, in the early 1960s. Robert Sisson/National Geographic Creative.

The Great Archaeologists focuses on the lives and achievements of 70 figures in this story, who between them have recreated those lost civilizations and distant cultures. Men such as John Lloyd Stephens, the rediscoverer in the 1840s of Maya cities lost to the jungle for a millennium, whose hunch that their undeciphered hieroglyphic script found on stone stelae would reveal dynastic histories had to wait until the 1970s and 1980s to be vindicated. He wrote lyrically of the city of Copn, silent under the rainforest, the only noise being monkeys trooping overhead. Today, this great Maya city is a major tourist destination, the forest long cleared from its spectacular temples and plazas. Then there were women such as Mary Leakey who, with her husband Louis Leakey, began working in Olduvai Gorge, in what is now Tanzania, in the 1920s, convinced that here they would find fossils of the earliest human ancestors, but who had to wait until 1959 before making the first crucial discovery of just such a fossil and who went on after her husbands death to unearth at Laetoli, also in Tanzania, the very footprints of an early ancestor, 3.6 million years old, preserved in the ash from a volcanic eruption. The dedication, determination and sheer derring-do of such figures comes across vividly in the pages that follow.

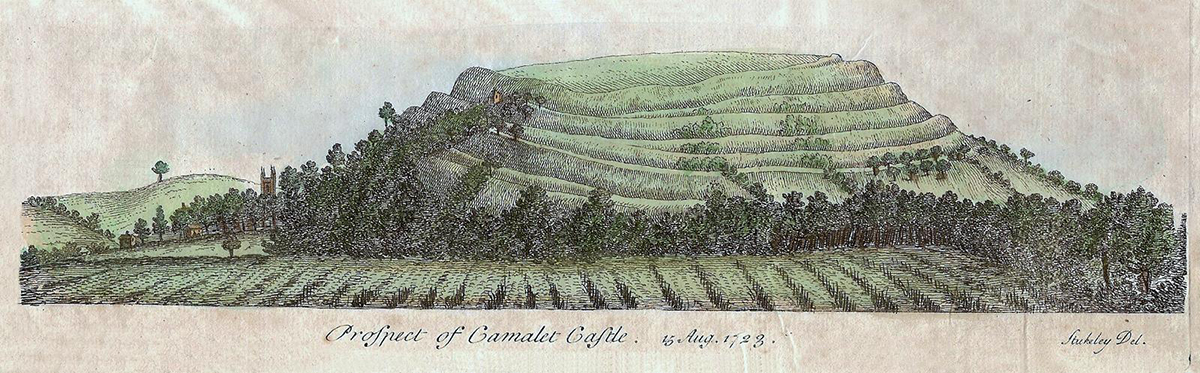

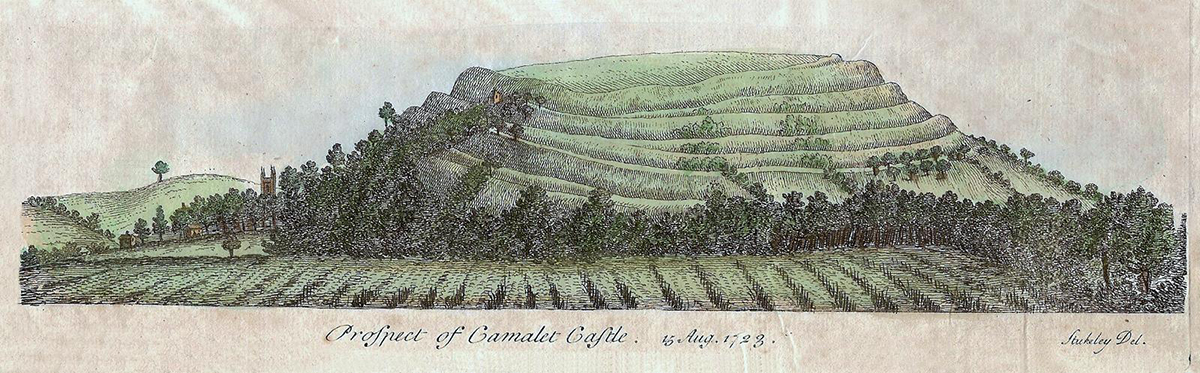

William Stukeleys Prospect of Camalet Castle, 15 August 1723 (Cadbury Castle, Dorset). Stukeley was an excellent draughtsman, and his drawings and plans capture many of Englands ancient monuments as they appeared in the 18th century. From William Stukeley, Itinerarium Curiosum, 1776.

We have chosen to focus on deceased archaeologists partly for reasons of space, partly because their achievements can be brought into sharper focus with the benefit of the passage of time, and partly so that their careers over a full lifetime can be assessed.

Six broad themes can be said to characterize the history of archaeological discovery, and they form the basis upon which The Great Archaeologists is organized. The first breakthrough came with the revelation in the 19th century of the high antiquity of humankind. Explorers and archaeologists in that century and the early part of the 20th century then transformed our knowledge by discovering the great ancient civilizations, the subject of our second section. To achieve those discoveries archaeologists began to develop much more scientific methods of excavation, which we examine in the third section. Crucial to an understanding of the peoples who created the early civilizations was the decipherment of previously unreadable scripts, from Egyptian and Maya hieroglyphs to cuneiform and Linear B, whose decipherers are celebrated in the fourth section. In the succeeding section we look at how intrepid archaeologists in far-flung parts of the world began to reveal a truly global prehistory, from Africa, Australia and the Pacific to China and Peru. Finally, we turn to how archaeologists have thought about the past how they have tried to interpret and explain how cultures evolved.

Next page