Credits and permissions can be found on page 291, which constitutes a continuation of this copyright page.

First published 2001 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2001 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

A CIP catalog record is available from the Library of Congress

Designed by Jeffrey P. Williams

Set in 11.5-point Perpetua by Perseus Publishing Services

ISBN 1 3: 978-0-8133-4-113-2 (pbk)

If man has indeed made himself, he has only been able to do so by means of his economies.

Grahame Clark, Economic Prehistory

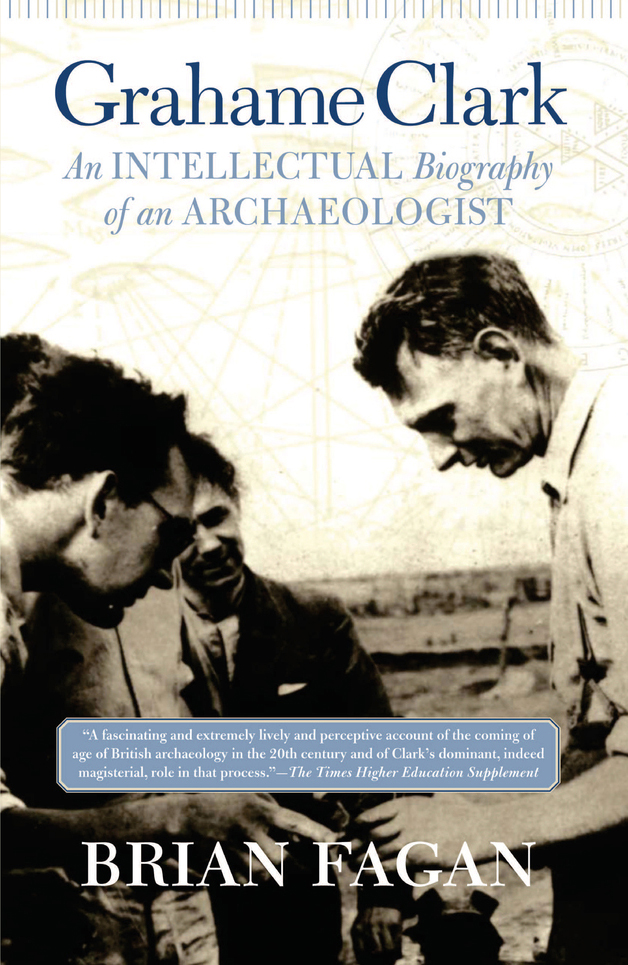

If, forty years ago, someone had predicted that I would write a biography of Grahame Clark, I would have laughed at such a ludicrous thought. Although I studied under him as an undergraduate and he supervised my graduate research, we never enjoyed much sustained conversation. In fact, I was terrified of him, confusing shyness for austerity. It was only when I started fieldwork on Iron Age villages in what was then Northern Rhodesia in 1960 that I realized the enormous influence he had exercised on my thinking. This intellectual mentorship continued during my doctoral research, much of it conducted far from Cambridge, and some of his ideas became part of my own thinking about the prehistoric past.

Many years have passed since I submitted the final draft of my dissertation into Grahames formidable hands, and he was friendliness itself on the rare occasions that we met in later years. He had mellowed, and so had I, and it was deeply satisfying to encounter him in Cambridge when I delivered the first Geoffrey Bushnell Memorial Lecture in 1992 and had a chance to tell him in his old age just how much I had learned from him. Even then, the thought of my writing his biography would have strained the bounds of credibility.

Time and chance brought me to the role of biographer, the passage of time honing my writing skills and chance taking me to the Grahame Clark Memorial Conference at the British Academy in London in November 1997. At the end of the meeting, I was cornered by Professor John Coles, one of Clarks literary executors, who invited me to become his biographer. After considerable soul searching, I accepted. This book, written at the formal invitation of Lady Clark and the literary executors, is the result.

I undertook the task with considerable trepidation but soon found myself engrossed in a complex, multifaceted life and in a journey that took me back to the nearly forgotten bucolic world of prehistoric archaeology in the 1930s, then to the Cambridge of the 1940s and 1950s and of my own undergraduate days. To chronicle Grahame Clarks intellectual life is to participate in the history of a discipline that he transformed, at first almost single-handedly, from something that was little more than artifact classification into a sophisticated study of the human past based on collaboration with scientists from many disciplines.

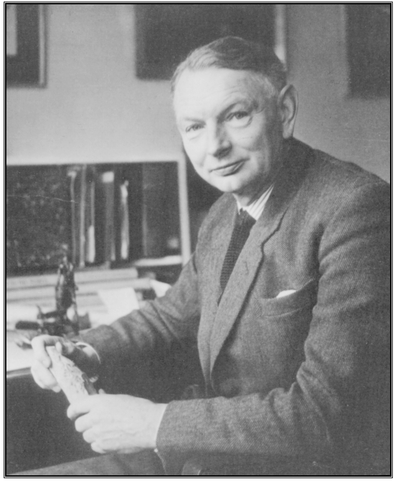

Grahame Clark was a very private man, with an austere, sometimes forbidding exterior. The public Grahame was a very different person from the private one. His archaeological friendships were relatively few, his acquaintances legion. He hid his emotions and preferred to talk about archaeology rather than exchange small talk. Stories of his awkwardness with students and others abound, but they are irrelevant to the biographer of a man whose intellectual influence on archaeology was enormous. Grahame Clark is one of the few archaeologists about whom the comment that Sir Christopher Wrens son made on his monument in Saint Pauls Cathedral is apposite: Si monumentum requiris, circumspice (If you seek his monument, look around you). His books and papers on archaeology, as well as the students he trained, many of them now gray-haired, surround one on every side. Clarks legacy to prehistory will endure for generations.

The history of archaeology has become a vigorous specialty within the discipline in recent years at three levels. The first is at a general level, that of anecdotal histories. Then there are intellectual assessments, such as the Canadian archaeologist Bruce Triggers History of Archaeological Thought , which is on the reading list of every serious student.especially for a researcher with many commitments, limited field time, and a base over 5,000 miles from the archives. In the case of Grahame Clark, I sensed that there was little to be gained from such research, for the main outlines, and indeed details, of his intellectual life are available in the public eye, and also in his own prolific writings. My concern with this book is to provide an assessment of his lifes work for working scholars with a general interest in the development of archaeology, not for historians of archaeology. I think more detailed historiography, if appropriate, is best left for a future generation.

Quite apart from the issue of historiography, the writing of this biography presented unusual challenges. Clarks executors gave me unlimited access to his archives, which are deposited in the Cambridge University Library, including the manuscript of his last, incomplete book, A Path to Prehistory , which he ultimately intended to call Man the Spiritual Primate .In the event, the archives contained almost nothing of historical value, for Clark tended to destroy correspondence after dealing with it. The few letters that survive are not particularly illuminating. Much of his archive consists of notes on long outdated academic papers and research materials for his many books and papers, all of which are on public record. Fortunately for a biographer, Clark was a compulsive writer who published not only every piece of fieldwork and analysis he completed (which makes him almost unique among archaeologists) but also several almost hidden autobiographical sketches, the most important of which appears in his Archaeology at Cambridge and Beyond (1989). His ideas and syntheses are fully published too, facilitating the task of an intellectual biographer. Accordingly, this biography is written in large part off Clarks own publications, a task that has involved reading virtually everything that he ever wrote, from his days as a Marlborough College schoolboy to his old ageI must be the only scholar ever to do so!