William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

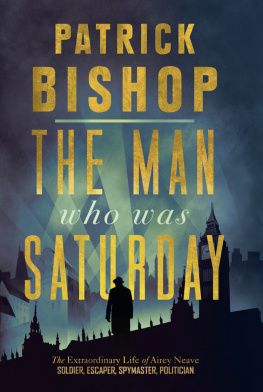

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright Patrick Bishop 2019

Cover design and illustration by Leo Nicholls

Maps by Martin Brown

The publishers have made every effort to credit the copyright holders of the material used in this book. If we have incorrectly credited your copyright material please contact us for correction in future editions.

Patrick Bishop asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008309046

Ebook Edition March 2019 ISBN: 9780008309060

Version: 2019-02-15

TO MARY JO, THOMAS AND MARTHA ROSE

Contents

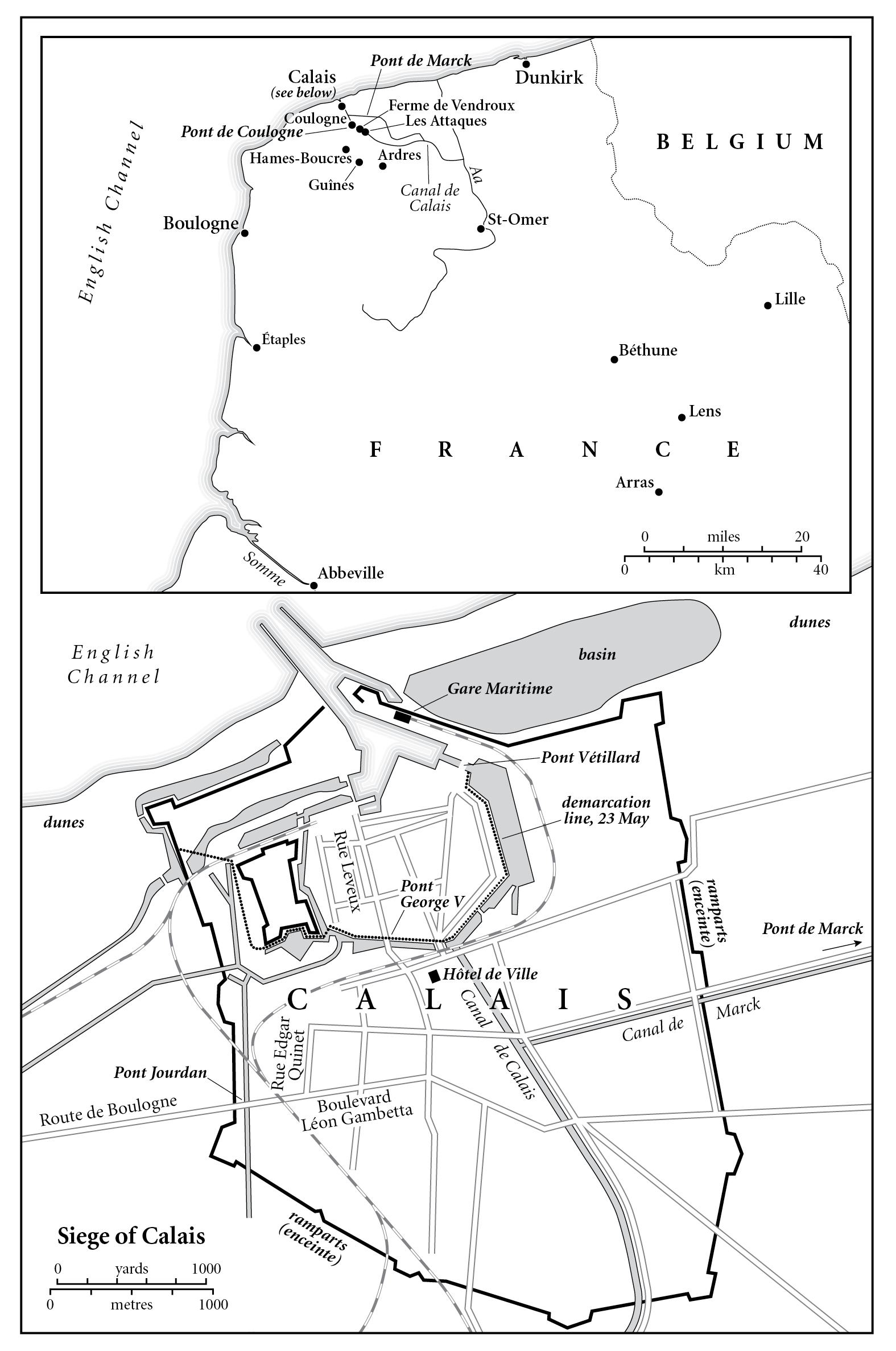

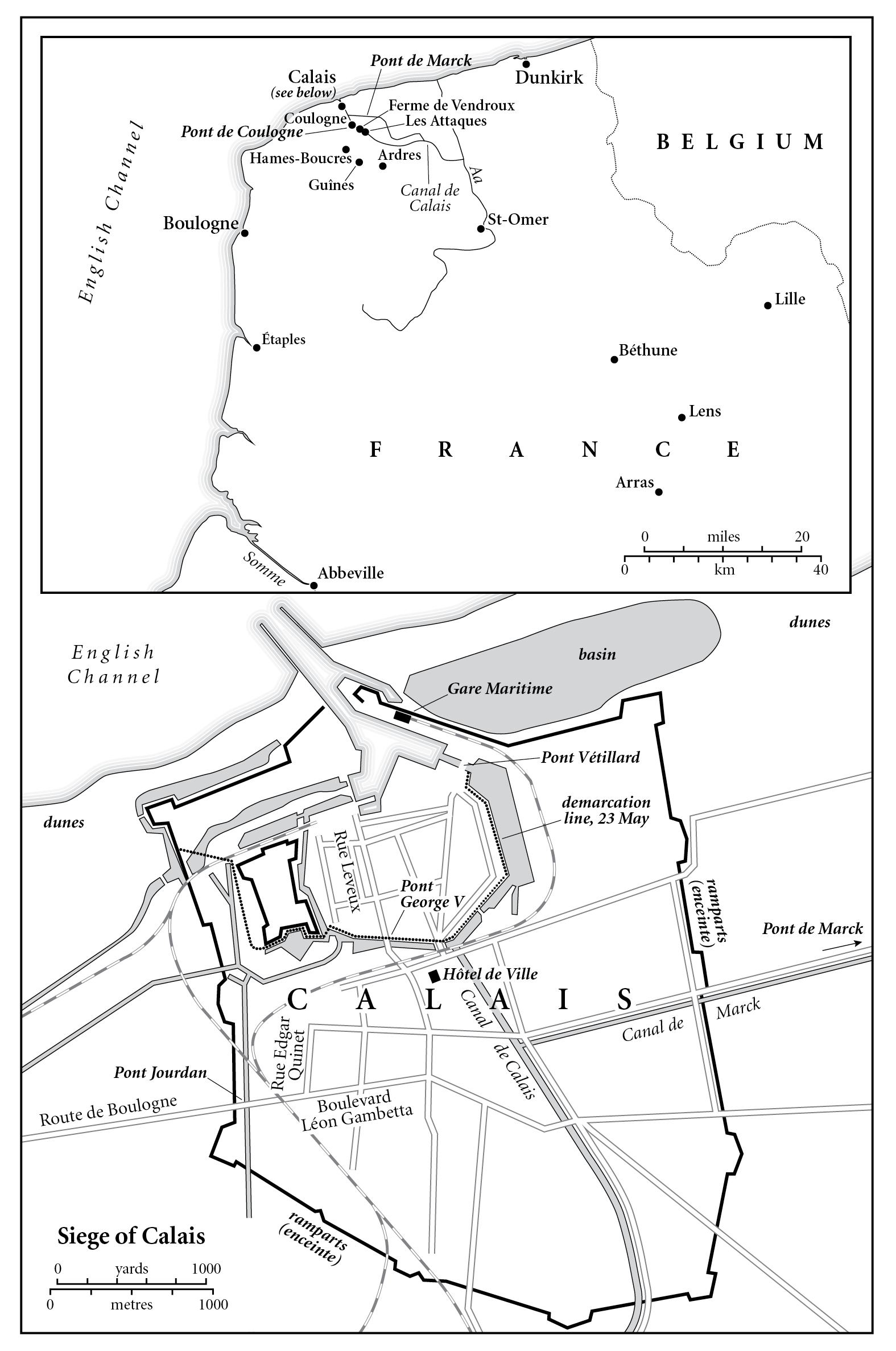

The siege of Calais

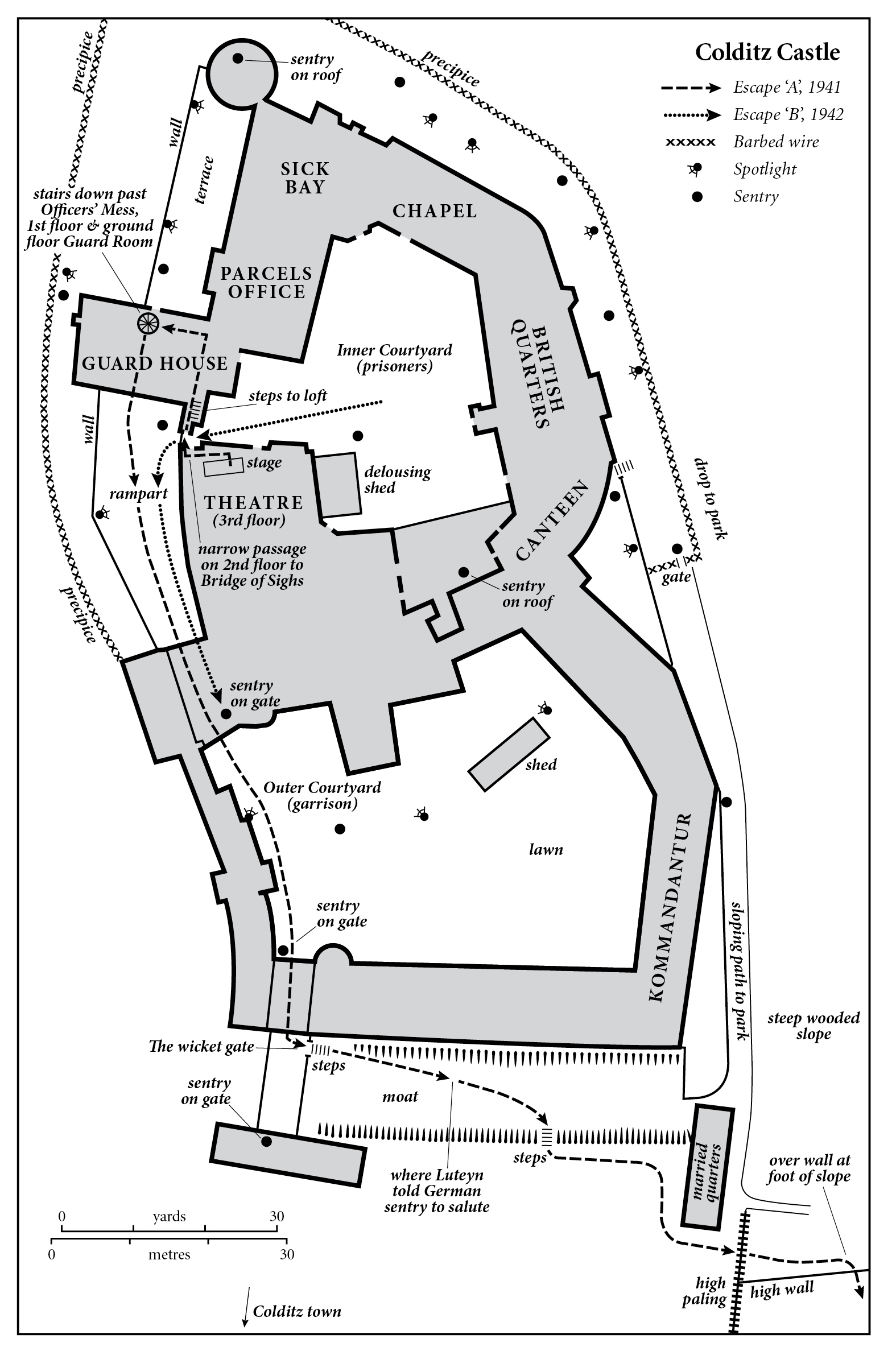

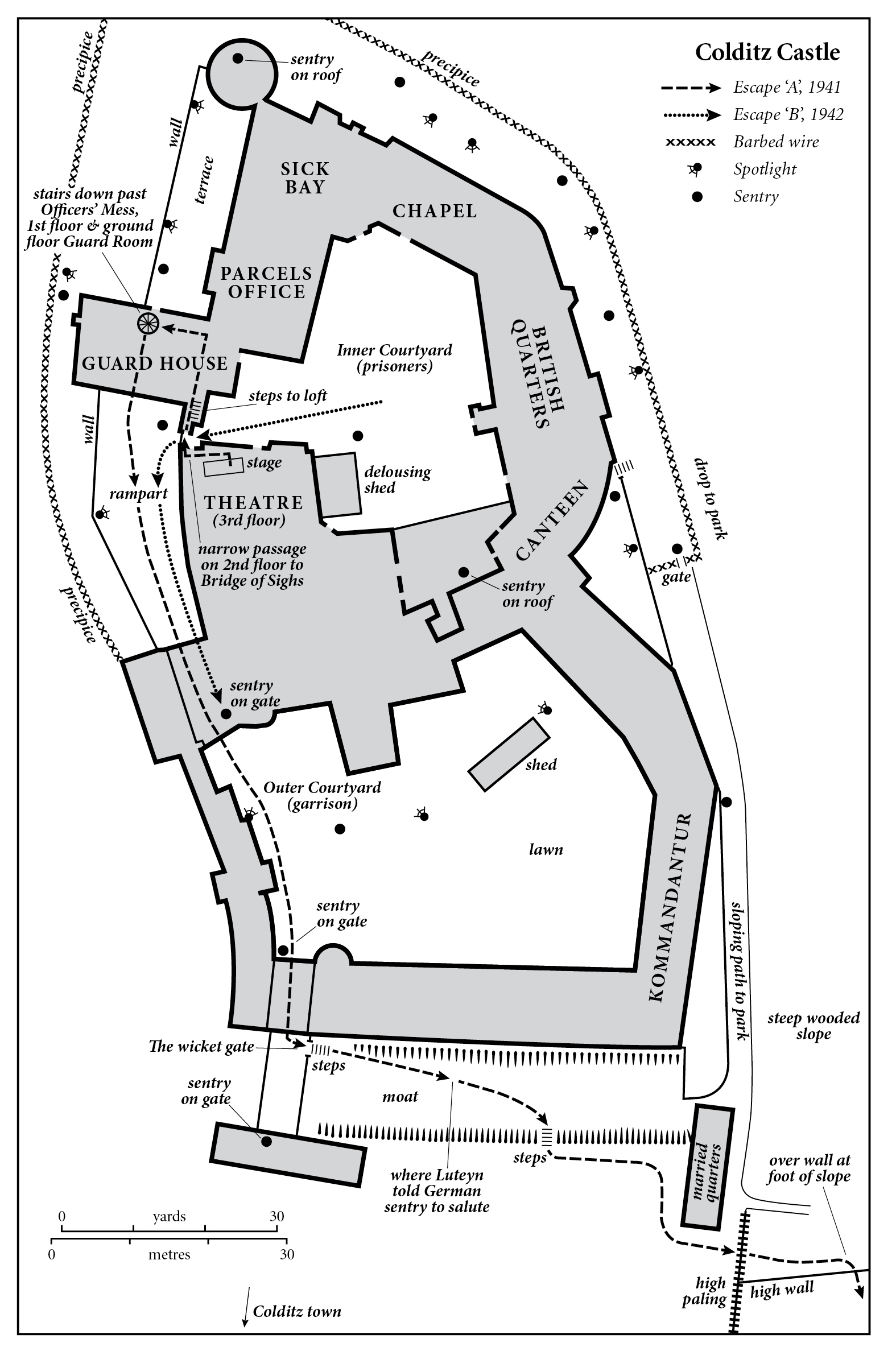

Plan of Colditz Castle

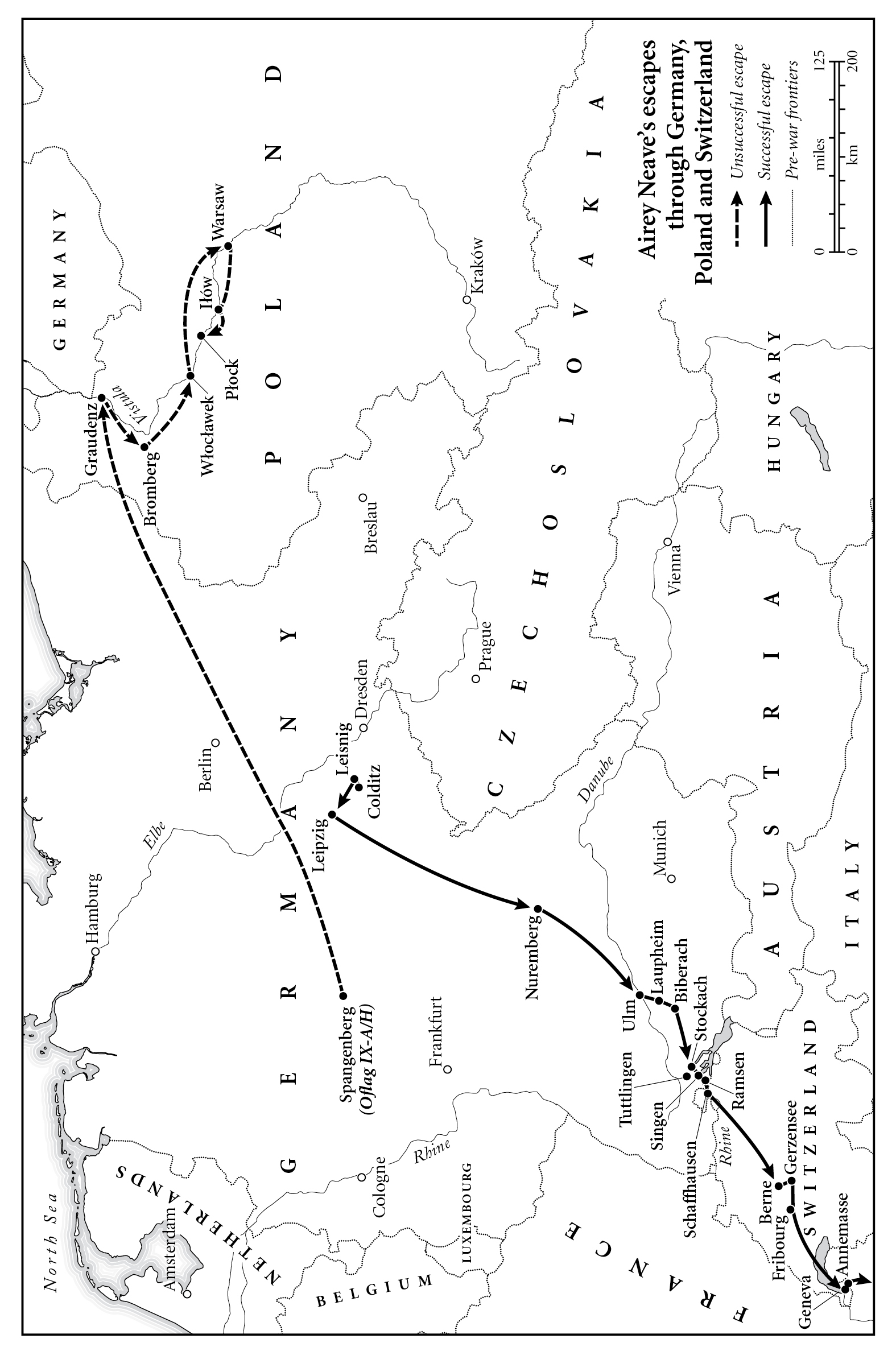

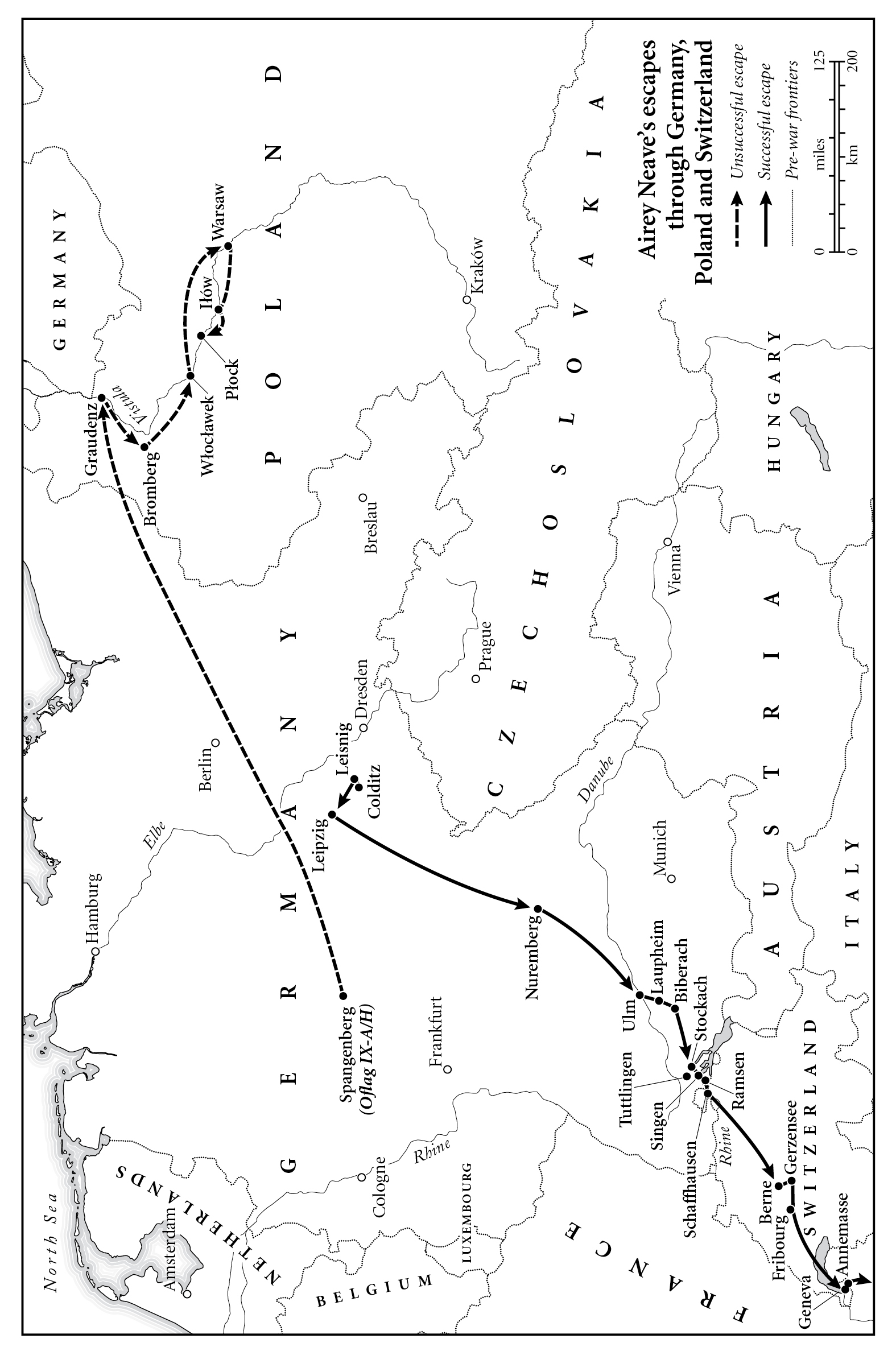

ANs unsuccessful and successful escapes through Germany, Poland and Switzerland

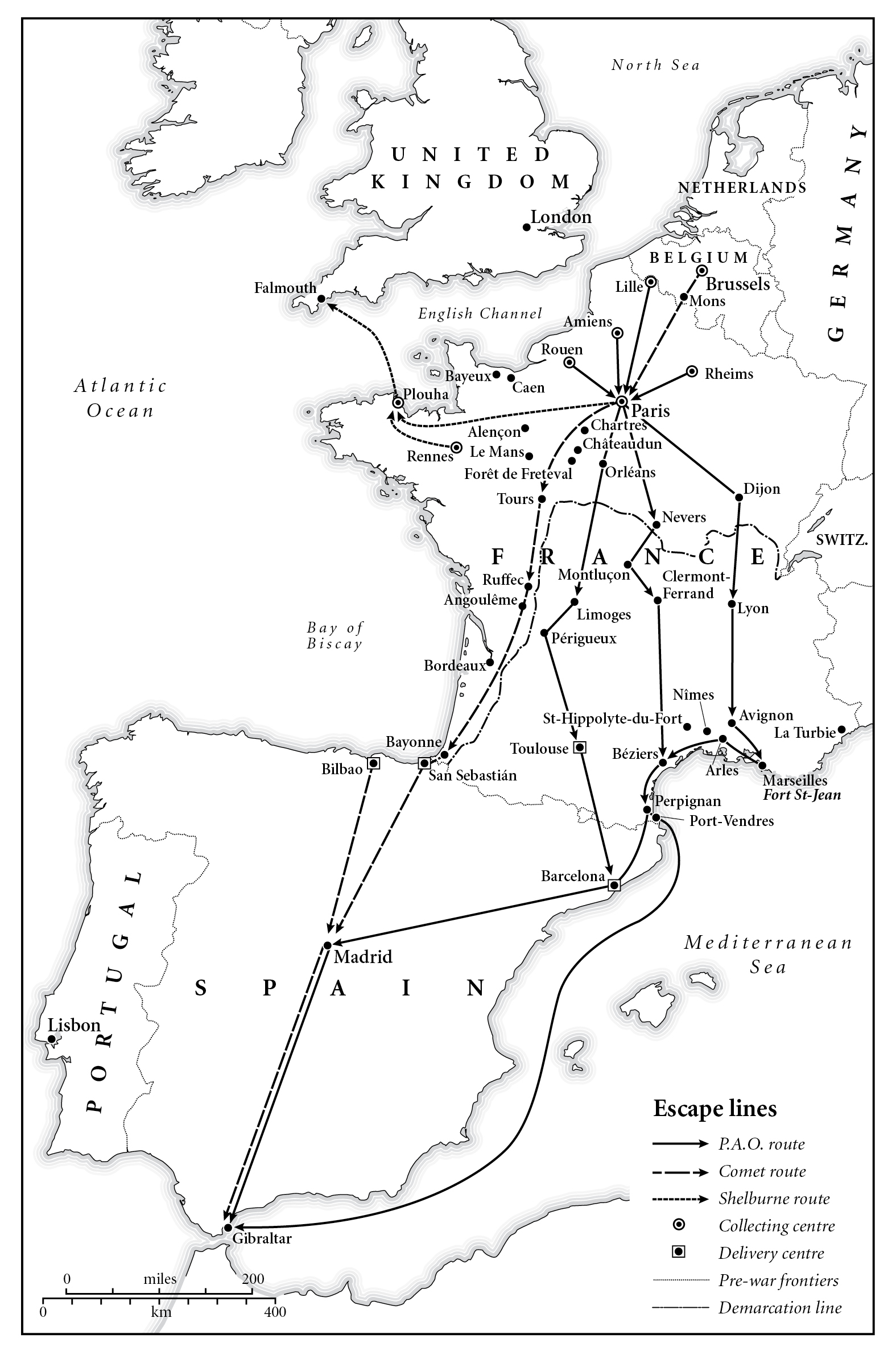

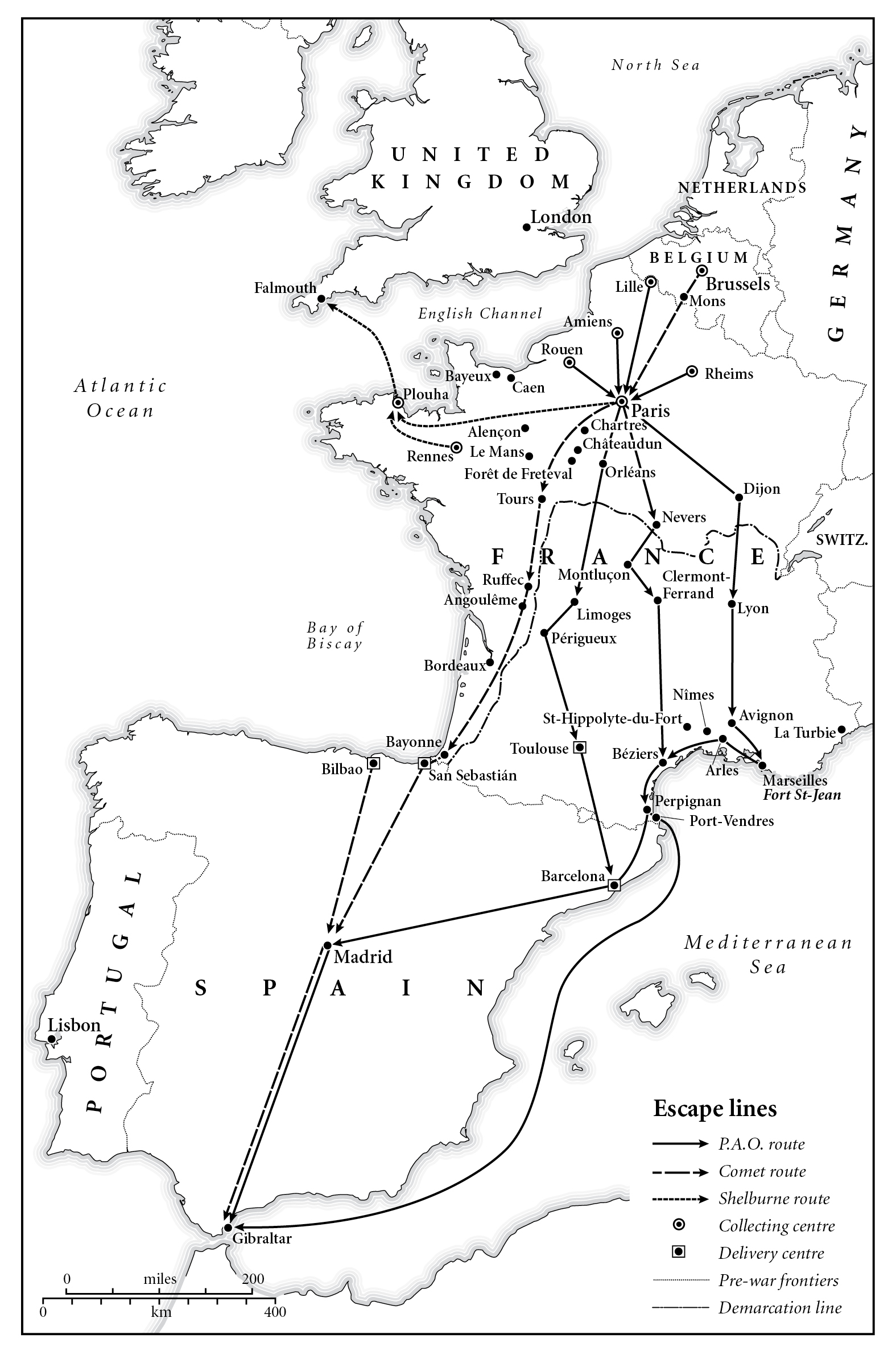

Escape lines operated by Pat OLeary and Comet in France and the Low Countries

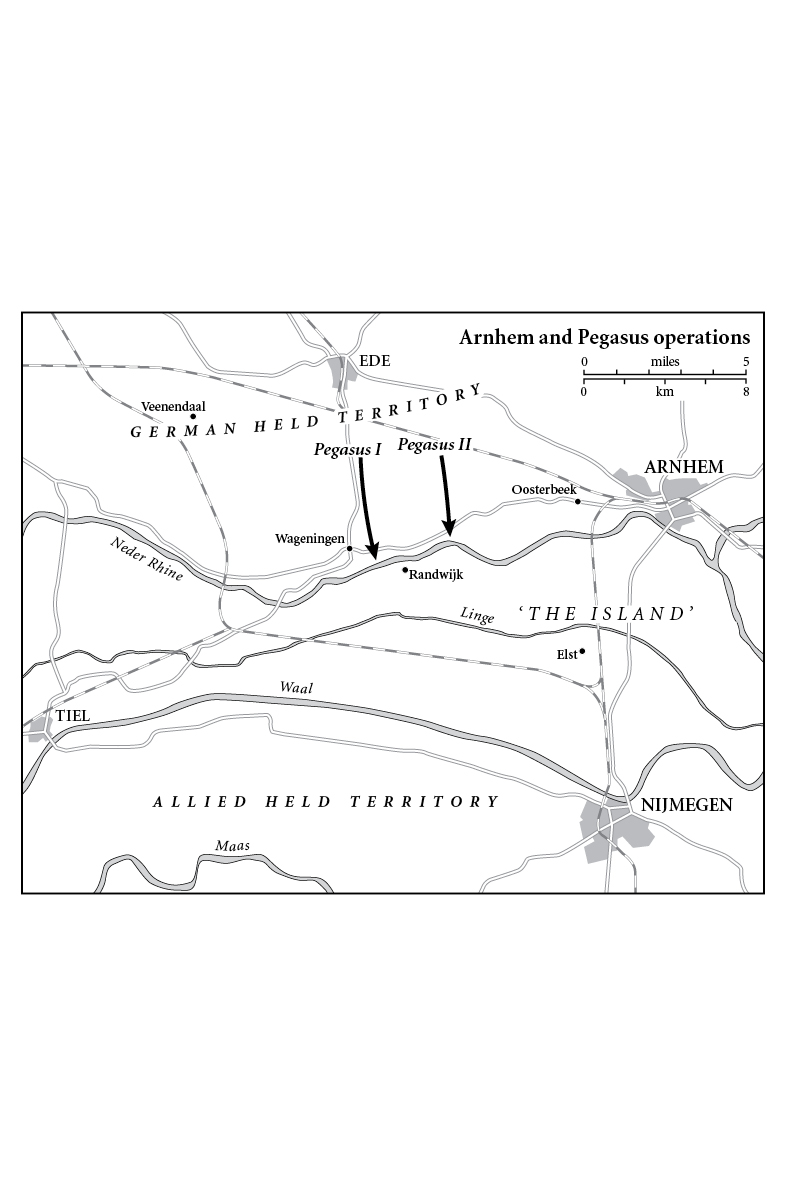

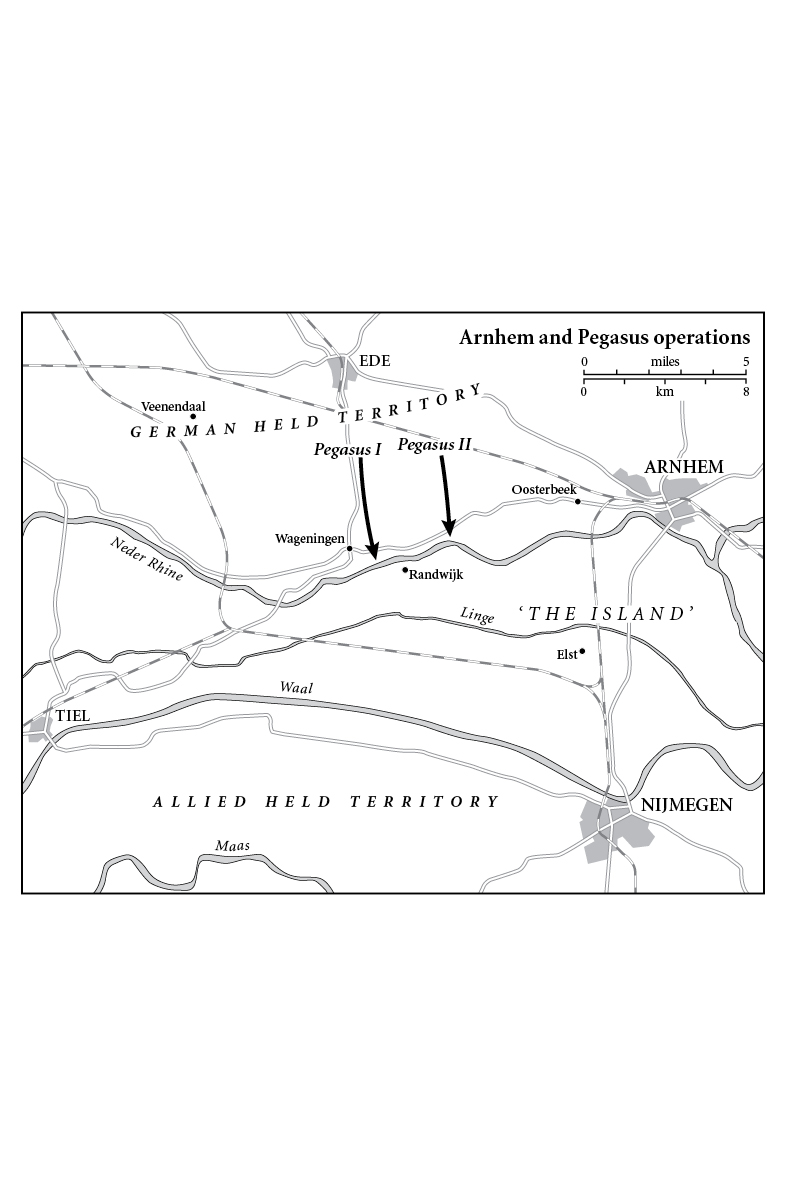

Arnhem showing Pegasus operations

Biography masquerades as history but is often a species of fiction. That is not necessarily the fault of the biographer. Establishing the external facts of a public life in modern, well-documented times is fairly straightforward. It is charting the inner landscape that is the problem. How can we know what someone really thought, what drove him or her to do this or that? Letters and diaries open a window on these processes, of course, but can we be sure the motives and feelings they reveal are genuine, and not retouched with an eye to the good opinion of posterity?

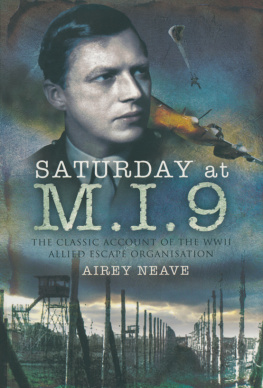

In tackling the life of Airey Neave I have leaned on two versions of who he was. The public one is laid out in the several memoirs he published based on his service in the Second World War. The other is contained in the voluminous diaries he kept covering crucial years in the last period of his political career. The frequent introspective and unsparing passages make it hard to believe they were written for anyone but himself. Thus I felt I had the basis for something like a reasonably authentic portrait: Neave as he would like to be seen and Neave as he saw himself.

There is another very important viewpoint Neave as he appeared to everyone else. Neave struck many of his contemporaries as inscrutable. The face he presented to the world was conventional and confident. This was to some extent an act. Behind the bland mask lay a very different personality: racked by insecurities, plagued by doubts and depressions and haunted by a sense of failure and underachievement. Studying his life confirmed for me the truth of the words of the country priest whom Andr Malraux met when serving with the Maquis in the mountains of south-eastern France. Asked what he had learned about humanity from the many confessions he had heard over the years, he gave the answer The fundamental fact is that there is no such thing as a grown-up person.

I find that answer moving and heartening. It is said to be a hazard of writing biography that familiarity breeds contempt and in the course of the research the author comes to loathe the relative stranger they blithely shacked up with at the start of the project. I am happy to say that for me the experience had the opposite effect. I came to like Neave a lot. He had his faults: vanity, touchiness, a dissatisfied nature. But they are greatly outweighed by his virtues: physical bravery not in short supply among his generation but also moral courage, quiet patriotism and a basic decency.

All came to an end in a shocking death at the hands of the forces he had been opposing in one way or another all his life. He led an interesting one, and his story has a satisfying curve. The adventures and achievements of his early career seemed to promise a glowing future. Instead, there followed years of frustration that sometimes brought him close to despair. Then, unexpectedly, the stars aligned to deliver a success that was all the more satisfying for its late arrival. He lived through a period of history which, though fairly recent, now feels curiously remote. What follows is an attempt to reanimate both him and his time.

Prologue

On Friday, 30 March 1979, change was in the air. For much of the month the weather had been cold and wet, but lately it had warmed up and in London the trees were in bud. The change of season matched a great political climacteric. Two days before, the Labour administration of James Callaghan had finally stumbled to an end after months of public-service strikes, already notorious as the Winter of Discontent. In five weeks, a general election would in all probability elect a Conservative government with, for the first time in British history, a woman at its head.

When Airey Neave woke up that morning he had every reason to savour the atmosphere of promise and renewal. As the man who had engineered Margaret Thatchers accession to the Conservative leadership, he had played a crucial part in great events. At the age of sixty-three, after a long wait and many disappointments, he was about to taste real power.

As a reward for his services, Mrs Thatcher had offered him any shadow portfolio he wanted. To the bafflement of many, he picked Northern Ireland. Political progress in Ulster was at a standstill and political violence a fact of everyday life. It seemed a masochistic choice. Neave saw it as a challenge a last chance to bring off an achievement that would leave his mark in history. Since adolescence he had been opposing those he saw as the enemies of democracy as a soldier, a prisoner of war, a Colditz escapee and an intelligence officer. The position of Secretary of State for Northern Ireland would put him in command of the latest phase of the struggle Britains war against Irish terrorism. The thought gave him great satisfaction.

A pleasant weekend lay ahead. He would be spending it in his Abingdon constituency with his wife Diana in the Oxfordshire village of Hinton Waldrist, where they rented a wing of the Old Rectory. Before leaving, he had some business to attend to at his office in the House of Commons. At 9.30 a.m., he left the family flat at 32 Westminster Gardens, in Marsham Street SW1, telling Diana he would be back to collect her at 3.30 p.m. The big nine-storey block was built in the 1930s and the apartments were spacious and comfortable, an ideal London base for politicians and senior civil servants.