Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

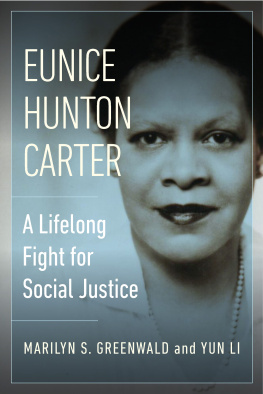

To Leah Cristina Aird Carter,

without whose dedication, imagination,

research, travel, interviews, love for the subject,

and keen editorial advice the project would have been impossible.

This book is hers as well as mine.

They wove a spell and took possession of one, yet all the while one was conscious of a certain familiarity.

E UNICE R OBERTA H UNTON , Replica (1924)

The raids were set for nine p.m.

So secret were the targets that the one hundred sixty New York City police officers involved were not allowed to see their orders until five minutes before the hour. They were told to wait on specified street corners for final instructions. Corruption in the city was that bad. If the cops had known in advance where they were going, the suspects would have been gone long before the raids started. So they waited, stamping their feet against the winter chill. In the frigid night air, their breath formed a faint curling mist. It was February 1, 1936, an icy cold night to be chasing some colored woman lawyers crazy theory.

At eight fifty-five, the orders were opened. The targets were brothels, eighty in all, some of them fancy townhouses, others no more than tiny back rooms. All were believed to pay tribute to the Mob leaders who ran crime in the city.

The police went in as scheduled. At most addresses they knocked and were admitted. At some they broke down the doors. They found women and men alike in various stages of undress. One woman fled partly unclad down a fire escape. Some of the customers climbed out windows. Others slipped past the cops and into the street. This was not difficult, because few of the raids comprised more than two or three officers. But most of the men were detained. Many were prominent city professionals: lawyers, bankers, civil servants. The orders were to question the men long enough to get evidence that prostitution was taking place, then let them go. The women were handcuffed, taken to the station houses for booking, then transported in taxicabs and whatever else was available to the Woolworth Building, on lower Broadway, at this time still one of the three tallest in the world. They rode the freight elevator to the thirteenth floor. The thirteenth floor was usually unoccupied but tonight was buzzing with activity, for it had been taken over for the next few days by the team of lawyers assembled to work with Thomas Dewey, the special prosecutor for organized crime. One of the lawyers logged and tagged the women as they arrived. Her name was Eunice Carter, and she was both the only woman and the only Negro on the team.

Months earlier she had come up with the theory that the Combination, which controlled prostitution in the city, was run by Lucky Luciano, the most powerful Mafia leader in the country. Dewey had been skeptical but had finally agreed to let her look into it. Eunice had drafted another lawyer to help. Together they had assembled the evidence and badgered Dewey until he yielded. The team had convicted some minor organized crime figures, but Luciano had proved untouchable. There was no way to connect him with the multifarious businesses, legal and illegal, from which he took a cut. Everyone was scared of him. He had risen to the top by ruthlessly eliminating those above him and those who were his equals, including some who had helped him in his climb. No one would testify against him. So Dewey had agreed to try Eunices idea.

The February raid produced a wealth of witnesses and leads, and as evidence against Luciano mounted, he slipped out of the city. He turned up in Hot Springs, Arkansas, famous at the time both as a place to gamble and as a place for fugitives to hide out. Local authorities kept finding reasons to keep him there rather than let him be extradited. Finally the state attorney general intervened. The mobster offered him a $50,000 bribe. To no avail. The judge told Lucianos lawyers he had no choice but to send him to New York. Three city detectives accompanied him on the train ride northward.

Lucky Lucianoknown to his intimates as Charley Luckywas more than another powerful gangster. He had, in a sense, invented the modern Mafia, arranging for power to be shared among several families rather than vested in the traditional capo di tutti capi . He had devised the system under which the heads of the families would meet regularly to set policy and settle disputes. And he had, until recently, successfully kept his name out of the headlines. But here he was, under arrest, hauled into court like any other mobster.

Lucianos trial on prostitution charges was held not in the New York criminal court building but in the civil courthouse on Foley Square, on the ironic ground that it was easier to fortify against a possible Mafia assault. There were guards everywhere. Not since the Civil War, the papers clamored, had New York City seen such armament. Forty patrolmen on foot and six on horseback kept back the surging crowds outside the courthouse. Two dozen detectives were posted in the courtroom or just outside. These were in addition to court officers and sheriffs deputies without number. Newsmen and photographers thronged the hallways.

In June, to widespread astonishment, the jury convicted Luciano of compulsory prostitution. Eunice, listening to the verdict in the courtroom, probably kept her usual poker face. But she must have felt a certain satisfaction. She was black and a woman and a lawyer, a graduate of Smith and the granddaughter of three slaves and one free woman of color, as dazzlingly unlikely a combination as one could imagine in New York of the 1930s, and without her work the Mafia boss would never have been convicted. She was an ambitious woman and had plans. She was just shy of her thirty-seventh birthday, and had come a long way from her segregated Atlanta childhood. Hers was the idea that had put away the countrys biggest gangster. In the process she had become one of the best-known Negro women in America. She would receive honorary degrees, be featured in Life magazine, lecture around the world, be handed medals and plaques from civic organizations everywhere. She would become a prominent and influential figure in the Republican Party. Her professional future seemed to pulse with bright and endless possibility. As she sat there on that fine June afternoon, she must have believed that she had only to reach out her hand and choose a direction.

Eunice Carter was my grandmother. This book is her story.

* * *

Eunice died when I was in high school, and I remember her mainly as a stern and intimidating woman of advanced years. She had a younger brother, Alphaeus, who would have been my great-uncle, though I have no memory of having met him. But, as I have learned while at work on this project, he figured prominently in her life. I have never known my forebears as well as I should have. My parents, like so many others in the darker nation, shared the family stories of achievement but omitted the details of racial slights and discrimination, as if the telling were subject to what the historian Jonathan Holloway describes as a psychologically enduring editors pencil. So for me, writing this book has been a journey of discovery, both about my own family and about the history of the community that Eunice and Alphaeus, in very different ways, tried to serve. In the process, I have gained a richer understanding of the world that formed my grandmother, and perhaps, as well, a greater sympathy for her habit of holding her grandchildren at a stern distance.