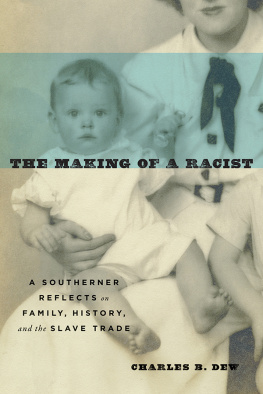

THE

MAKING

OF A

RACIST

A SOUTHERNER

REFLECTS on

FAMILY, HISTORY,

and the SLAVE TRADE

CHARLES B. DEW

University of Virginia Press

2016 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2016

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dew, Charles B.

Title: The making of a racist : a southerner reflects on family, history, and the slave trade / Charles B. Dew.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015043815 | ISBN 9780813938875 (cloth : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780813938882 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Dew, Charles B. | Dew, Charles B.Family. | HistoriansSouthern StatesBiography. | Southern StatesBiography. | Southern StatesHistoriography. | SlaverySouthern StatesHistory. | Slave tradeSouthern StatesHistory. | RacismSouthern StatesHistory. | Southern StatesRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC E175.5.D49 A3 2016 | DDC 306.3 /620975dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043815

In memory of

Illinois Browning Culver

PREFACE

I have been doing my best to make sense of southern history for as long as I can remember. Trying to understand my native region has been the central preoccupation of my intellectual life almost since I learned to read, and, even before that, the South and race were presented to me in the stories my mother read to me, as I describe at the beginning of chapter 2.

I have been teaching southern history now for more than fifty years, and in my classes I have found myself returning over and over again to stories from my childhood and early adulthood as I try to describe to my students how I was raised and how the process of my upbringing imparted the views and beliefs that constitute the core of the first two chapters of this book: my Confederate youth, and the emerging attitudes and beliefs that made methere is no other way to say thisa racist, an accidental racist perhaps, as my friend the novelist Anne Tyler might put it, but a racist nonetheless.

My students remember these stories. Because they are personal and because they are hearing them from someone who lived it, these scenes from my youth seem to resonate with them; they invariably ask probing questions in class and often stop by my office to continue our discussions. So I decided to write it down. It was not easy. But I found that once I got started, the material began to flow, my memory kicked into gear, and I would often be at my desk for hours on end. I remembered things and events and scenes and conversations I had not thought about for many years. It was almost as if I needed to get this story out.

The result is a strange combination of autobiography and historythe story of my growing up on the white side of the color line in the Jim Crow South, my engagement as an adult with southern history, and the power of the past, and on occasion a single piece of documentary evidence, to rock us back on our heels and send us off in a quest for understanding. In my case, as I describe in chapter 4, one document, a printed broadside generated by the Richmond, Virginia, slave trade, was just such a piece of historical evidence. It sent me to the archives on a dismal journey: to read as many of the surviving letters of Richmonds slave traders, their agents, and their customers as I could get my hands on.

While I was engaged in researching and writing this book, a scholarly outpouring of remarkable depth and breadth focusing on the domestic slave trade in the United States occurred. This began with Maurie D. McInniss brilliant Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade, which appeared in 2011. Her book was followed in rapid succession by four equally impressive studies: Walter Johnsons River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom, published in 2013; Sven Beckerts Empire of Cotton: A Global History and Edward E. Baptists The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, both published in 2014; and Calvin Schermerhorns The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 18151860, which appeared in 2015.

Maurie McInnis proved herself as adept at slave history as she was at art history, and the result was the most accurate and detailed portrait we have ever had of the Richmond slave-trading community, its personnel, its physical setting, and the art that came into being as observers turned their attention to the scenes that unfolded in slave traders auction rooms. The Johnson, Beckert, Baptist, and Schermerhorn studies all drive home a point of transcendent importance: this traffic was absolutely vital for the antebellum rise of the Cotton Kingdom in the Deep South, and in the course of filling the Lower Souths voracious demand for labor, the basic contours of American capitalism took shape in the nineteenth century.

All five of these studies deserve the widest possible readership; anyone who does this will be stunned by the extraordinary research, the deft writing, and the impressive interpretative analysis that went into each of these volumes. I learned an enormous amount from them. But, in the end, I decided not to add a discussion of this scholarship to this undertaking. Certainly the material I present in the second half of this bookthe letters of the Richmond slave tradeconfirms the thrust of this new scholarship, but I read these letters with a different purpose in mind: I was trying to get inside the minds of the white participants in the citys human trafficking to see if I could come to grips with how my peoplesouthernerscould engage in this abhorrent business and not see the evil inherent in what they were doing. But the documentary evidence I have presented about the Richmond slave trade certainly complements this new scholarship, giving, I hope, added depth to the story told in these five extremely impressive volumes.

So, to repeat, I have written a strange hybrid, a combination of autobiography and history that does not fit neatly into any category of writing with which I am familiar, something my father would have called a different breed of cat. But I hope what I have written down here will resonate with at least some readers in ways that parallel the reaction of many of my students over the years: something remembered that helps them understand how the South of our day came into being, something that helps explain the racism that for far too long has poisoned the atmosphere of the place where I was born and raised. If I manage to bring some readers along with me on this journey, I will have accomplished what I set out to do.

CHARLES B. DEW

WILLIAMSTOWN, MASS.

Introduction

THE STUFF OF HISTORY

I love to teach from original documents, and my favorites tend to be those I turned up myself during archival searches. There is something special about the contact we make with the past by touching the stuff of historythe letters, the diaries, the record books, the broadsides, and other original materials that pass through our hands as we sit in those quiet and frequently beautiful manuscript reading rooms. We open a folder or a bound manuscript volume or pick up a printed broadside, and we suddenly discover something that changes how we view the history of a subject we are trying to unravel. On rare occasions, we find a document that alters how we feel about ourselves and what we are doing with our lives.

This is a book inspired by just such documents, and one document in particular. It has its origin in items I have found over the years that forced me to stop dead in my tracks and lay my pencil down on the table in front of me as I tried to come to grips with what I had just read.

Next page