Epilogue

What has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

John Dryden

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Lifes but a walking shadow; a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more:

It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Macbeth

All is flux, nothing stands still.

The way up is the way down.

Heracleitus

CHAPTER ONE

In Search of Wings

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward Ive climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hovring there

Ive chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

Ive topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace,

Where never lark, nor even eagle flew

And, while with silent lifting mind Ive trod

The high, untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

High Flight John Gillespie Magee (1922 41)

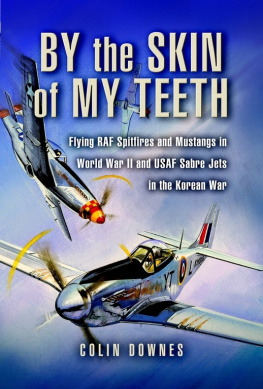

LAUGHTER-SILVERED WINGS AND CLOVEN TONGUES

The two world wars produced poetry of high quality and two poets in particular stand out in my memory. In the First World War a Canadian medical officer, John McCrae, wrote In Flanders Fields while serving at a dressing-station during the second Ypres Offensive in 1915. This poem became the most famous of the war and I always associate it with my father, who also fought during the second Ypres battle and was a survivor of the slaughter at the Battle of Loos. Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, RAMC, died on active service in 1918. In the Second World War an American pilot, John Magee, wrote High Flight, a poem that encapsulates all the sensations and joys of flying a high performance aircraft. Born in Shanghai of an American missionary father and an English mother and educated in England, John Magee volunteered from the United States for pilot training with the RCAF in 1940. The following year Flying Officer John Magee, RCAF, joined an RAF Spitfire squadron in England and died in a flying accident. The poem High Flight was among his effects.

From an early age my imagination and day-dreams drifted with airy navies battling in the central blue where real aces such as the Red Baron duelled with fictitious ones like Biggles. Both fighter pilots, and the Frog model airplane powered by elastic that I would launch on interception flights against kites flying over Parliament Hill Fields on Hampstead Heath, played a significant part in my aspirations to join the list of Aces. Against my vaulting ambition I had a foe named folly. Wellington said of Waterloo it was a close run thing; so it was for me to slip the surly bonds of earth and fly where never lark, nor even eagle flew.

To begin at the beginning: airplanes were always somewhere in my life and my first flight occurred in the late 1920s when at the tender age of six I travelled with my parents to the Belgian seaside resort of Blankenberg. We flew in the open four-seat cockpit of a French single-engine biplane flying-boat, taking off at Harwich on the Suffolk coast and landing at Ostend. I do not remember the reason for the trip or my inclusion. Perhaps it was after my nanny had left our household, which was why the weekend jaunt was a near disaster for my mother. My father was busy elsewhere and while walking along the crowded esplanade with my mother I managed to lose her. Luckily I was bilingual so, after the initial flood of fear and panic, I found a sympathetic policeman and a friendly police station from which a near demented mother retrieved me some hours later.

The pilot of the flying boat was a comrade at arms whom my father had met during the First World War while flying with the RAF in France. My father was in his first year of medicine at Edinburgh University when he volunteered for Kitcheners New Volunteer Army in 1914, enlisting in the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). After participating in the Battle of Loos in 1915, he suffered a severe wound in the chest during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. On recovering from his wound, he decided that living conditions in a tank were preferable to those in the trenches and transferred to the Royal Tank Corps. He fought as a tank commander in the third Ypres battle and in the tank battle of Cambrai in 1917, where he was wounded for a second time. In the preparation for the Battle of Amiens in August 1918, he volunteered for reconnaissance duty with the RAF to coordinate the operations of the tanks of 1st Tank Brigade with the artillery, the RAF and the Canadian Corps. He joined No. 52 Squadron flying RE-8s and it was here that he met the pilot who would be the main influence in developing my interest in aviation. After demobilization in 1919 this avuncular friend of my father continued flying and joined a major petroleum company and flew the companys DH Hornet Moth around the country to air displays and racing car meetings. He owned a diminutive, single seat Comper Swift, powered by a 70 hp Pobjoy engine. He knew Comper while in the RFC during the First World War, and he flew the Swift in air races. I thought this little monoplane the most beautiful of all aircraft and I would day-dream of the day when I might be able to fly one like it. Thanks to this generous benefactor my father and I flew to many air shows and air races around the country, and to the motor races at Brooklands and Donnington.

The war clouds were gathering over Europe in the late 1930s and having been brought up on a diet of First World War reminiscences together with a fund of battle tales, I knew it was only a question of time before I should have to respond to a call to arms. My parents had their own different reasons for deciding I should not go into the Army. My mother being French had spent the First World War in Bordeaux and had relatives in the French Army who had fought in the Franco Prussian War of 1870 71 and the Great War of 1914 18, and she had no wish to see her son fight in that sort of war. I remember with affection my mothers favourite uncle who saw action during the First World War, and in Indochina and North Africa. Graduating from the Ecole Militaire and the cavalry school at Saumur, he was the epitome of a French cavalry officer from a past generation. He wore a neatly trimmed moustache and dressed immaculately in the Edwardian style, and always with a boutonniere to match the red rosette of the Legion dHonneur on his lapel. His one regret was never to have led a cavalry charge in any of his wars. He died suddenly in Paris in 1977, the oldest living general in the French army. His ancestor was Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, the architect of the Gothic revival in France and noted for the restoration of medieval buildings and a dictionary of French architecture. On his one hundredth birthday the French Army gave him a birthday party, and with his erect, trim figure and full head of silver hair he looked twenty years younger than his age. His eventual departure at the age of 103 was both unexpected and a little bizarre; and no doubt to his regret. He was too old to die gloriously in battle pour La Patrie as he would have wished, but he could at least hope for a warriors end. However it was not to be; he died while entertaining a lady friend to luncheon at Maxims. In the enjoyment of the occasion; or in the excitement of the moment; or in anticipation of the afternoon to follow; he choked on a fish bone that even a 37 Chassagne-Montrachet failed to dislodge. His exit had a certain Gascon panache about it; although he came from the adjoining province of the Auverne. Because I lived in England I did not see this urbane and genial relative often but he left an indelible and illustrative mark in my memory of mores and of living in France during La Belle poque.