Bobbie Rosenfeld

The Olympian Who Could Do Everything

Bobbie Rosenfeld

The Olympian Who Could Do Everything

ANNE DUBLIN

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Dublin, Anne

Bobbie Rosenfeld : the Olympian who could do everything / Anne Dublin.

ISBN 1-896764-82-7

1. Rosenfeld, Bobbie, 1904-1969-Juvenile literature. 2. Athletes-Canada-Biography-Juvenile literature. 3. Sportswriters-Canada-Biography-Juvenile literature. I. Title.

GV697.R68D92 2004 j796'.092 C2004-900833-1

Copyright 2004 by Anne Dublin

Second printing 2004

Edited by Sarah Silberstein Swartz

Photo edit by Laura McCurdy

Index by Janice Weaver

Designed by Counterpunch/Peter Ross

Printed and bound in Canada

Second Story Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative.

Published by

Second Story Press

20 Maud Street, Suite 401

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5V 2M5

www.secondstorypress.on.ca

For my parents, Gail and

Morris Dublin, who have

always been my heroes.

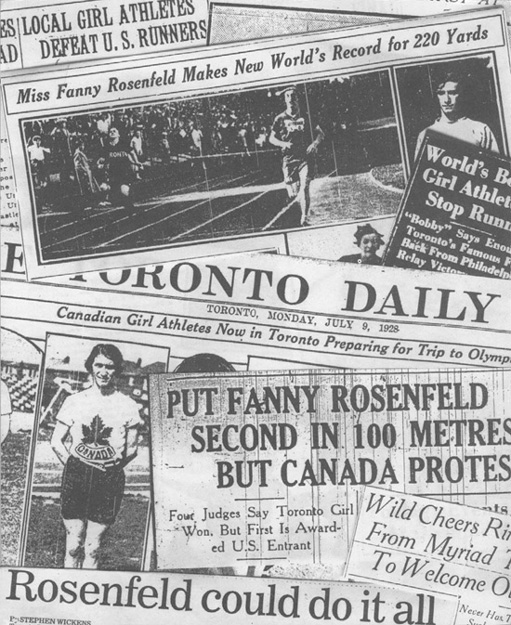

Sports history is replete with the names of forgotten competitors who established outstanding records in their day.

Bobbie Rosenfeld

Table of Contents

Introduction

Sports are an important part of life for todays young women and men. Girls and boys play hockey, softball, basketball, soccer, track and field, and many other sports. Young people enjoy athletics for fun, for recreation, for the love of the game. If someone is really good at a sport, he or she might even train with a coach. For those who are exceptional, the aim could be to compete in the Olympic Games, held every two years around the world. Whether its for fun or more serious goals, playing sports is good, healthy exercise for everyone. It teaches you to put your best effort into whatever you do.

But there was a time when opportunities for young people to become athletes were harder to find. Girls, in particular, were discouraged from playing games that were competitive and rough. Well into the 1950s, there was gender discrimination in sports. Girls were considered too fragile and sensitive to play hard and to play well. Doctors warned that competitive sport was bad for womens health. For years, even women sports educators agreed that girls should not strain themselves. Up until about fifty years ago, many girls had to disobey their parents in order to play the sports they loved. These girls were often labeled tomboys or roughnecks.

There were many theories behind this stereotype. Some people believed that competition might be too hard on their feelings and that girls would cry if they lost a race. Others believed it was indecent for girls to wear comfortable sports clothes that might show too much skin, like an ankle or an elbow. One medical theory was that if girls strained themselves by doing sports, they might be unable to have babies. The final argument was that young women who competed in unladylike sports would be less attractive to men and might end up without a husband!

Because of this gender discrimination, girls who wanted to play sports in a serious way experienced many problems. They often received inadequate financial support, inferior equipment and facilities, less convenient practice times, and inexperienced, if any, coaches and teachers. It was hard for young women to compete seriously in any sports event, even on an amateur level. As for professional sports, there was little place for women.

From our perspective in the twenty-first century, we might think these were foolish ideas. But many people up to the 1950s were convinced they were right. How have our attitudes changed?

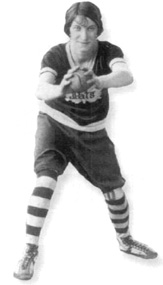

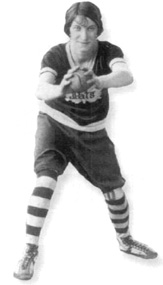

About one hundred years ago in a small town in Russia, a baby girl was born who would eventually make a difference in how people viewed women in sports. Despite all the obstacles she faced as a woman, she became one of the finest athletes Canada has ever produced. She excelled in many sports: track and field, ice hockey, basketball, softball, and tennis. When she was sent to the Summer Olympics of 1928 as part of the Canadian team, she won two medals. When she could no longer play sports, she coached. When she could no longer coach, she wrote a sports column for an important Canadian newspaper. And always, she was her own person.

When Fanny (Bobbie) was a teenager, many girls and women cut their hair in a new short style called a bob. Fanny cut her hair, too. From then on, everyone called her Bobbie.

She was a woman known for her strength and fair play on the sports field, for her wit and honesty off the field. She was one of the first athletes to be honored by Canadas Sports Hall of Fame. As the year 1950 came to a close, the most important sports writers in Canada voted her Canadas Female Athlete of the Half-Century A park was named after her, and a historic site devoted to her. Many years after her death, she is still remembered for her great athletic gifts. A fine athlete and advocate for amateur and womens sports, she remains a role model for young women athletes today.

Her parents named her Fanny, but the world came to know her as Bobbie Rosenfeld. This is her story.

1

Beginnings

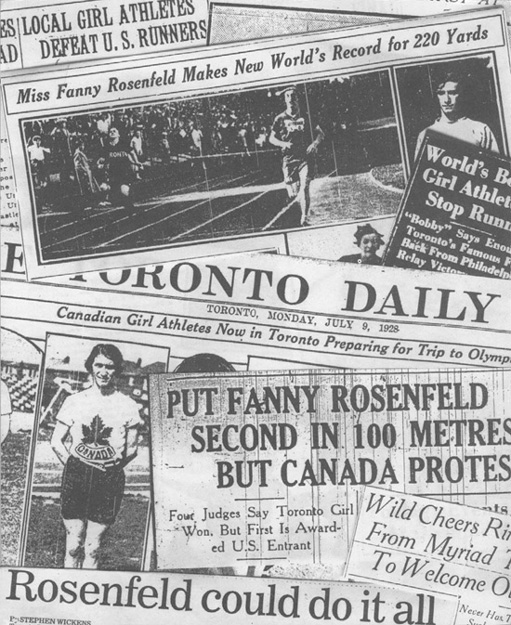

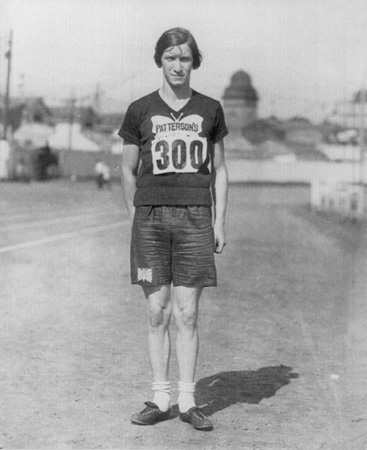

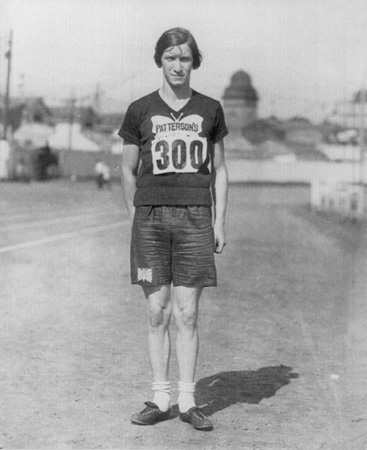

Above:Immigrants arriving at Union Station in Toronto, 1910. Facing page: Bobbie, ready for a race

Fanny Bobbie Rosenfeld was born on December 28, 1904, in the town of Katrinaslov, in the Ukraine, then part of Russia. She was the first daughter of Max and Sarah Rosenfeld, a Jewish couple who would take their two children, Bobbie and Maurice, to a new world in Canada.

The exact year when Bobbie Rosenfeld was born is unclear. Some sources say 1903 or 1904. Others suggest 1905. In those days, people did not always keep accurate track of birth dates.

In those days, Russia still had a czar, a powerful ruler born into that position, much like a king. But the workers and peasants were gearing up for a major uprising against him and his government. These people wanted a revolution. They were fed up with poverty and hunger, and the huge differences between the lives of the rich and the poor. They reasoned that if revolution had created freedom and liberty for the people in France and in North America, it could also work in Russia.

Many workers and peasants marched and demonstrated against the czars government. On January 22, 1905 - the day people would later call Bloody Sunday - Russian troops at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg killed more than one hundred peaceful marchers. It was only a taste of the upheaval and violence that was to come twelve years later.

Next page