This book has been written in response to the urgings and with encouragement from friends and others who have at some time heard me speak of the strange and unexpected experience that befell me in 1942. It was never intended that this should be another war book, but rather an account of an unusual event resulting from the war.

Together with forty-six officers and men, among which were the Rear Admiral Malaya, Rear Admiral E. J. Spooner, and the Air Officer Commanding Far East, Air Vice Marshal L. E. Pulford, I found myself marooned on a small tropical island midway between Singapore and Java. At first sight the island appeared to be a paradise, with its lagoons, palm-fringed beaches and luxuriant vegetation covering its rocky promontories almost to the point where they entered the sea. The reality was very different as we experienced its virulent swarms of mosquitoes and sandflies.

These were as nothing compared to the blanket of deep depression that settled with devastating effects on us all. It was something quite beyond our experience and expectation. It almost immediately led to a terrible debilitating lassitude as the hopelessness of our situation became apparent. One by one many simply lost the will to survive. Those of us who managed to hold out ultimately became Prisoners of War of the Japanese.

I have been advised by those versed in authorship of this kind that people who may read this account like to know what sort of a person you are and something of the events surrounding such an experience. This has led inevitably to a brief description of my early life and motivation; it thus includes some details of my wartime experiences.

It is an eye witness account of events and impressions by a junior officer at the time. The major incidents are indelibly printed on my mind and backed up by brief notes throughout the period covered by the book. On each occasion of loss, I rewrote them at the first opportunity. The last editions were secreted in the false bottom of my old Army pack when a Prisoner of War. Earlier notes up till the outbreak of war were taken from my journal kept officially by all midshipmen in the Navy.

I should like especially to thank my wife and family for their encouragement over the many years that I struggled with the manuscript. To Dr Sydney Hamilton for his many helpful suggestions and comments. Also to Jean Hunt and Pat Lawrence for deciphering my handwriting and typing the resultant manuscript. Lastly and perhaps most importantly to Marion Crinoch for her determination that the story should not be allowed to grow cobwebs any longer.

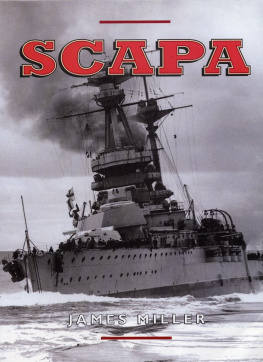

As far back as I can remember I was fascinated by water and anything that floated on it; first I made boats for myself, then model yachts, gradually moving up the scale to sailing and racing dinghies. I read everything I could find about real seagoing ships, especially warships.

My home at Felixstowe faced the sea, with the estuaries of the Rivers Orwell and Deben to the west and east, each with their typical Suffolk foreshores of marsh, dykes and oyster beds, so I had plenty of scope to practise and fulfil my interest. I found history an absorbing subject and was easily able to equate the two interests. Thus it seemed natural that I decided to enter the Navy. I had always been encouraged in this aim by my father, a general practitioner who had served as a Naval Surgeon during the First World War.

At thirteen and a half years of age, after a successful interview, I sat the written entry examination for Dartmouth. It was February, 1933, the recession was at its height, the competition was great, and I was not successful. This was a disappointing setback but my resolve remained as strong as ever and so it was decided that I should try to enter via the Nautical College, Pangbourne. This time I succeeded and entered Pangbourne in the autumn of the same year.

Life at Pangbourne was a continuous rush, or so it seemed. We ran, or in naval parlance doubled, everywhere, we were always changing from uniform to P.T. rig or games clothes of one kind or another. I was completely unused to the stiff collars of my uniform shirts and, by the time I had forced the stud through the stud hole and tied my tie, my collar was dirty and distorted.

I was terribly homesick and, although I never disliked Pangbourne, I longed for the holidays. When we did have any spare time, I often spent long periods just sitting on the hillside, the College being situated three hundred feet up on the Berkshire Downs, just gazing over the receding folds of the countryside to the east, imagining that beyond the most distant fold lay the marshes and estuaries of Suffolk.

The long summer holidays, when at last they came, were a constant delight, sailing and exploring the still unspoilt estuaries, guarded by their sand and shingle banks which were a challenging entry to the sea beyond, about which I spent so much time dreaming. The romance that I found in such books as Erskine Childers classic of pre-World War One, The Riddle of the Sands, became almost real as I gazed out into the North Sea mists. The vision of those childhood summers with their memories of hot sun, of the distant boom of the Lightship, of the Belle steamers arriving at the long pier, paddle wheels thrashing, of sailing and swimming, of trailing my dinghy over the Suffolk heathlands to crowded regatta days at Waldringfield and Aldeburgh these were all to stand me in good stead in the years to come, providing me with a will to see them all again.

These breaks apart, I lived the normal life of a boy of my age. I loved games and usually managed to struggle into the lower realms of most teams at the College. I was not academic and found studies hard, except for history and geography, which came easily.

One highlight of my time at Pangbourne came in July, 1935, when the whole College went down to Portsmouth and spent a day at sea in the Reserve Fleet ships to witness the Review of the Fleet by King George V on his Jubilee. My party was accommodated in what was then the Reserve Fleet Flagship, the cruiser Effingham. It was a perfect day and we were, as Cadets, enthralled by the spectacle of the assembled ships from the various Fleets then maintained by Britain at home and overseas. Each ship was dressed overall, with the many-coloured signal flags whipping and cracking in the stiff Spithead breeze and sunshine. It was a romantic view of the Navy but it strengthened my determination to succeed in my ambition.

At last, after three and a half years, in the summer of 1937 I once again sat an Admiralty Interview and written examination. Several weeks later, while I was on holiday, an OHMS envelope arrived to say that I had been successful. This was followed soon after by my first appointment By Command of the Commissioners for Executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom to Mr R. A. W. Pool Cadet R.N. directing me to repair on board His Majestys Ship