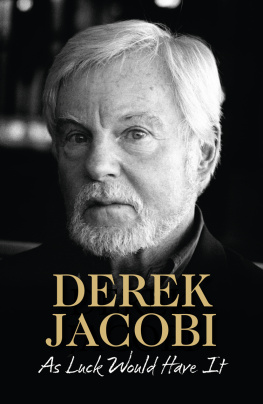

It shimmers and enchants; it belongs to a secret, magical, forbidden world, and I have always wanted it.

She keeps her glorious white silk wedding veil part of her wedding trousseau in her wardrobe, and I sometimes sneak into my parents bedroom and gaze at it. And then one day in 1945, when I am six years old and they are both out at work, I creep into their room, open the wardrobe and carefully lift out the veil. I drape the gorgeous white material round my shoulders and over my head, and, swishing it around and puffing myself up like mad, I go out of the house and parade up and down Essex Road.

We East London kids like to play out in the Essex Road and the adjoining streets, and do so in complete safety. The streets of England are our playground. We make dens in the front gardens, and dream and imagine we are other people and characters. From as early as I can remember I have been excited by the idea of dressing up, and this is my first recollection of being in costume.

Perhaps it is to impress Ivy Mills that I have worn Mums wedding veil, though my first girlfriend is Winnie Spurgeon. We play hopscotch, and doctors and nurses, with two other girls in the street and we chalk our initials on the pavement. Yet it is Ivy, the prettiest of the three, who has now become my favourite. The boys in my class start to chalk on the pavement, DJ LOVES IM, and I will do anything to please her.

But on this day I know Im not just pleasing Ivy. I know in some instinctive way that I am performing, perhaps for the first time in my life, and suddenly all the world or at least Essex Road is my stage. And in transforming myself, and entertaining Ivy, I have a sudden insight a sense of who I am, and who I could be, when Im not just being myself.

I can become other people in my imagination but cant we all? I can be a hero or villain, strong, weak, timid, arrogant, crafty, trusting, passionate, destructive, nurturing ... I can be anything I want to be. After all, Im a human being, full of everything you can possibly imagine.

Of course Ivy, Winnie and my friends laugh at me and are most impressed. I play up to it for all its worth strutting, waltzing, skipping, galloping around the pavement until my veil is finally shredded to bits on the front garden privets.

Mum was back home when I returned. She was waiting.

Well, this is it, I thought. Shes going to go completely bananas at me when she finds her precious wedding veil torn into tatters!

I was starting to cry as I stood there ready for her to tear me to shreds just as I had torn her wedding veil.

But her reaction wasnt anger: she hardly told me off at all.

From that moment I continued to fancy myself in the veil. The idea of the veil stuck in my mind as a garment that, whoever wore it, both concealed and revealed the person. Yet the actor in me, the dressing-up part of me, was a mystery which I never could understand, right from the beginning and that still remains the case today. I can only describe it as a magical process.

Later I would say that the actor must somehow have got in there right from the start, at the moment of conception, but God knows where he came from. Was I simply born an actor, as grandly titled by Edmund Kean A prince and an actor a part which I was to play later in Jean-Paul Sartres play? Even then, in that earlier time as a child, the first part I ever acted was a prince, and this prince was by no means to be the last.

We take it for granted that actors can act; the skill or craft or the trick is to make people believe they are seeing somebody real on stage, not an actor acting. Ideally they should leave the theatre talking about the person theyve seen and the emotions theyve felt, not saying, Gosh, isnt he a good actor? That suggests that it has been merely a spectator sport, and the actor has been showing off. Audiences or viewers want to believe they have been in the presence of a real person.

But theatre, film and television are trickery; a bit of a performance works, and I glow to myself. I know Ive managed to carry it off, and it is a moment of pure, private pleasure. As every actor does, I have felt the power and the glory of trickery and mystification.

Yet who would ever have suspected that that little boy who was so excited at putting on his mums wedding veil would in time come to play real and fictional people Hamlet, Lear, Hitler or Alan Turing, and a great host of others? Who could ever have known that he would come to live in the palaces or grand locations of his games and imagination, or re-inhabit in stories the real places, such as Bletchley, or the suburbia-like lower-middle-class Leytonstone, which had an importance in his early life?

It was the fate and destiny established way back in my past, in my childhood or before, that there would be many, many parts, well over the 200 mark through my seven ages, behind which I would hide my true self, conceal myself as behind a veil, yet at the same time be able to reveal some of who and what I was.

I dedicate this book to Mum and Dad,

and to my teacher, Bobby Brown.

All the worlds a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurses arms.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannons mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipperd pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Shakespeare, As You Like It, II, vii.

CONTENTS

It was all a ghastly mistake. The state of the world at that time was such that no one thought of having a family. Hitler was already advancing fast and the world was on the brink of war when I was born in East London on 22 October 1938.

This was in our front room in Leytonstone. My mum Daisy struggled in labour for forty long hours to give birth. Forty hours! Has anyone ever taken so long to be born? It must be a record. Mum was completely worn out, and when at last Id been delivered she sank back and groaned, Never again!

Is this what its all been about? said our doctor, as he held me up with just his right hand to show Mum and Dad. Mum and I were then placed in an improvised oxygen tent to recover. She had no more children.

The labour may have been endlessly protracted and I was probably the most appallingly mewling, puking infant, but from that moment on I was the sole object of my parents love and attention. They lived for me, exclusively and without reservation. Each Christmas Day, for instance, I would wake, rub my eyes and gaze in utter wonder at my presents at the end of the bed: not one but two pillowcases stuffed full of presents of every kind games, toy trains, Meccano, jigsaws all just for me!