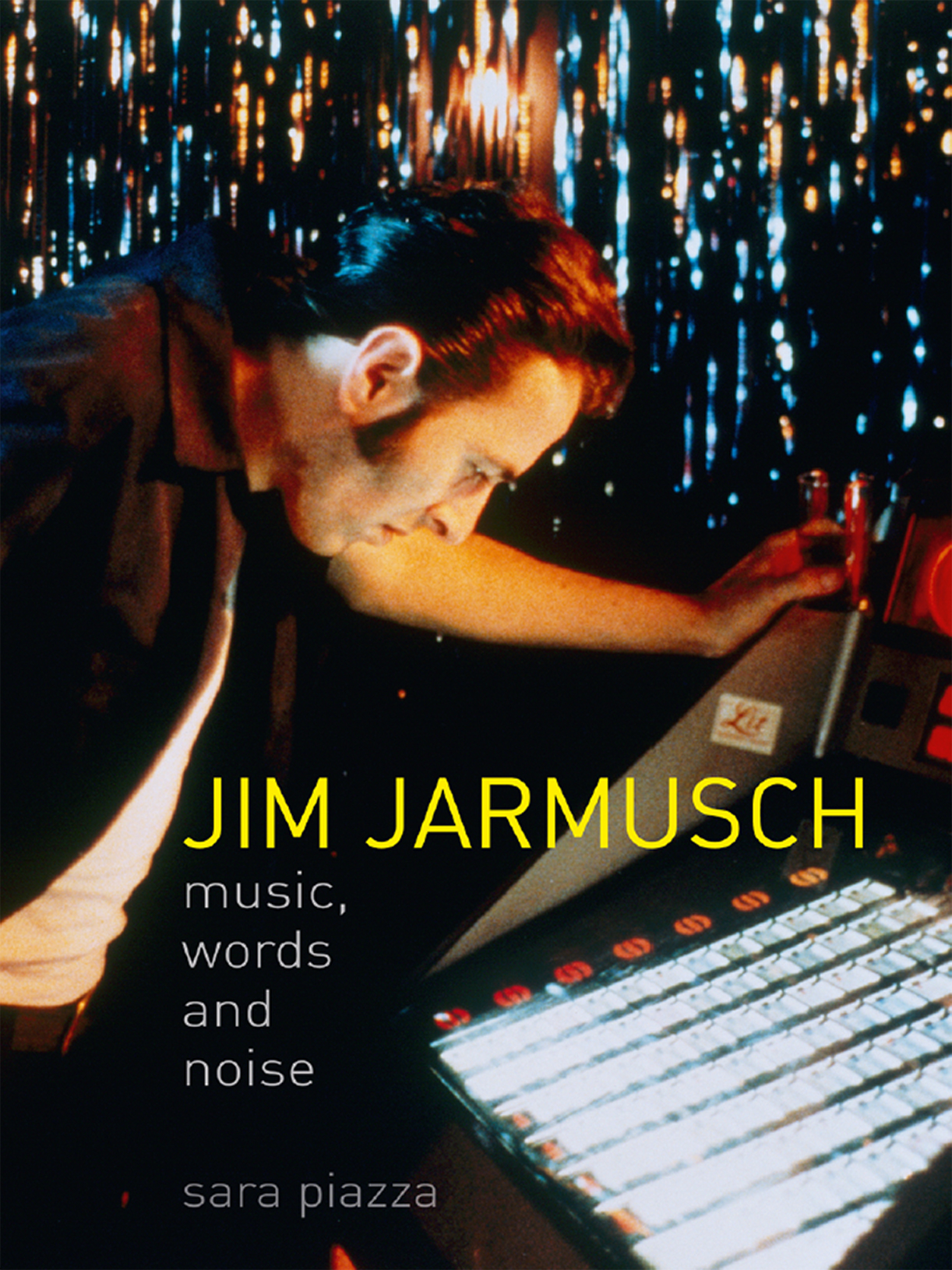

JIM JARMUSCH

Jim Jarmusch

music,

words

and

noise

sara piazza

REAKTION BOOKS

To BAMALU, for having been there all the time

In loving memory of my Maria

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Sara Piazza 2015

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234694

Contents

The blind vendor, M, dir. Fritz Lang (1931).

Introduction

In the spring of 1931 just four years after the official advent of the Talkies a German film made history by, among other things, showing in an undisputable manner the expressive and narrative power of the invisible on the screen: Fritz Langs M. Apart from the bulging eyes of Peter Lorre in the role of child killer Hans Beckert, what also strikes the memory of those who have seen the film is without a doubt the melody that Beckert whistles to his little victims before abducting and killing them. In the Hall of the Mountain King was composed by Edvard Grieg for Henrik Ibsens Peer Gynt and today its popularity has transcended the theatre by entering into everyday life partly, it must be said, thanks to the telephone companies around the world often using it as a standard ringing tone. In M it is this melody that betrays Beckert, and it is a detail of no small consequence that the one to discover and report the killer is an elderly, itinerant vendor who has lost his sight. A small but eloquent sign hanging from the old mans neck declares him to be Blind, an adjective that works in both German and English and alluding perhaps to the use of the written word so typical to the title cards of silent cinema clears up any misunderstanding: it is hearing, far more than sight, that demonstrates itself to be the decisive sense in the disturbing story told by Lang in his first sound film, the key to which is a simple whistle.

The apparently banal act of whistling is in reality far more complex than it might seem due to containing melody, voice a vehicle for word and finally an acoustic signal, and so synthesizing in a single sound material all three fundamental acoustic layers that make up the non-visible sphere on film: MUSIC, WORDS and NOISE.

It is these three invisible mainstays that will bolster my journey into the cinema of Jim Jarmusch, whose career kicked off roughly 50 years after the release of Langs film and in New York, at that time an island-city very similar to West Berlin. According to Jarmusch:

Berlin is an incredible city. It seems to be very similar to New York in terms of tension and atmosphere, but for very different reasons. Like being a walled-in island, torn in half, with the constant military presence.

In 1987 he lived in Berlin for almost a year and his reference to the military presence naturally alludes to the atmosphere of a city that at the time was still cut in two by 43 km of brick and barbed wire. And as my acoustic journey through Jarmuschs cinema does not adhere to a chronological order, but instead explores the three sound mainstays of audio-vision Music, Words and Noise this is the right place for a brief panorama on certain moments of that 30-year career before I move on to illustrate the structure of the book.

Allie in the Lower East Side, Permanent Vacation. |

|

Following its initial film-school mishaps, Permanent Vacation attracted the attention of the critics: it was awarded the Josef von Sternberg Award at the 1980 Mannheim Film Week in Germany, and in February 1981 it was shown at the young cinema Forum section of the Berlinale. Despite these early successes, the film was not released commercially. The year 1982 saw the start of the long production journey of Stranger Than Paradise, the film that consolidated Jarmuschs place as an independent filmmaker on the international scene. Released in its definitive three-episode version only in 1984, it was initially conceived as a 30-minute short entitled The New World, about a Hungarian teenager who comes to New York from Budapest. In the feature-length version, the journey continues to Cleveland and then Florida. An outsiders perspective on America, on its cultural melting pot and its interior and exterior landscapes, is a theme that Jarmusch would continue to develop over the course of the years. The European success of Stranger Than Paradise, winner of the prestigious Camra dOr for the best debut film at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, certainly made it a lot easier and faster to produce the next picture, Down By Law (1986), in which, other than John Lurie, who had already starred in Stranger Than Paradise with Eszter Balint and Richard Edson, two of Jarmuschs close friends and collaborators Roberto Benigni and Tom Waits played leading roles. Down By Law also sanctioned the start of a long partnership with the Dutch director of photography (and Wim Wenderss regular associate) Robby Mller, confirming another fundamental characteristic of Jarmuschs modus operandi: surround yourself with familiar faces, especially with regard to the crew. Mller is a good example, as are editor Jay Rabinowitz and soundman Drew Kunin, both Jarmuschs frequent collaborators.

In Down By Law, the adventures of the three friends/enemies Jack, Zack and Bob, accidental cellmates and equally accidental fellow escapees through the swamps of Louisianas bayous, gave Jarmusch the opportunity to continue not only exploring the image of America, its literary and musical culture, but also its film genres: the prison or escape movie, gangster movie, road movie, western, samurai, noir, romantic comedy, episodic film, vampire story all labels that, possibly also combining more than one, may be affixed to Jarmuschs films. And yet I believe this labelling would be a mistake or at least an excessive simplification. Genre in Jarmuschs cinema is a pretext, scaffolding that does not necessarily conceal a structure as one might expect. The ingredients are there, but the recipe has a different, unexpected flavour. Jarmusch explained in his own words just how much genres are a fluid and personal concept for him, as is evident in Mystery Train (1989), his film tribute to Memphis and its musical traditions. In the liner notes for Mystery Trains soundtrack CD Jarmusch defined the film as a triptych including three separate but connecting stories, like those Japanese films made up of several ghost stories, or the Italian ones consisting of romantic comedies. What cannot be argued, however, is that Jarmusch wrote his next screenplay very quickly, and alone: Night On Earth (1991) was to be filmed in five different cities, its cast made up mostly of Jarmuschs actor-friends. The moment of suspension of a taxi ride is the narrative nucleus of a film that, at least on paper, must have appeared to Jarmusch like a walk in the park when compared to the tortuous western project he had just shelved. In reality, it was not exactly like that. As remembered by a very diplomatic Frederick Elmes, the films director of photography: