Also by Ha Jin

Between Silences

Facing Shadows

Ocean of Words

Under the Red Flag

In the Pond

Waiting

The Bridegroom

Wreckage

The Crazed

War Trash

A Free Life

The Writer as Migrant

A Good Fall

Nanjing Requiem

A Map of Betrayal

The Boat Rocker

A Distant Center

COPYRIGHT 2019 BY HA JIN

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Permissions Company, Inc. on behalf of Copper Canyon Press for permission to reprint an excerpt of Tu Fu to Li Po from Cool, Calm and Collected: Poems 19602000 by Carolyn Kizer. Copyright Carolyn Kizer. Reprinted permission of The Permissions Company, Inc. on behalf of Copper Canyon Press (www.coppercanyonpress.org).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Jin, Ha, [date] author.

Title: The banished immortal : a life of Li Bai (Li Po) / Ha Jin.

Other titles: Life of Li Bai (Li Po)

Description: New York : Pantheon, 2019. Chinese versions of his poetry will be included. Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024328. ISBN 9781524747411 (hardback). ISBN 9781524747428 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : Li Bai, 701762. Poets, ChineseBiography. Li Bai, 701762Criticism and interpretation. BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY/Literary. LITERARY CRITICISM/Poetry. HISTORY/Asia/China.

Classification: LCC PL 2671 . J 554 2019 | DDC 895.11/3 [B] dc23 | LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2018024328

Ebook ISBN9781524747428

www.pantheonbooks.com

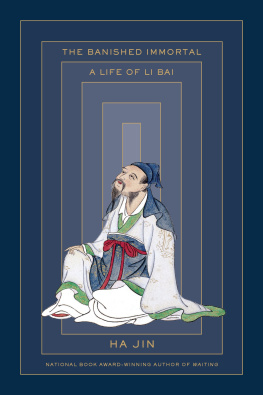

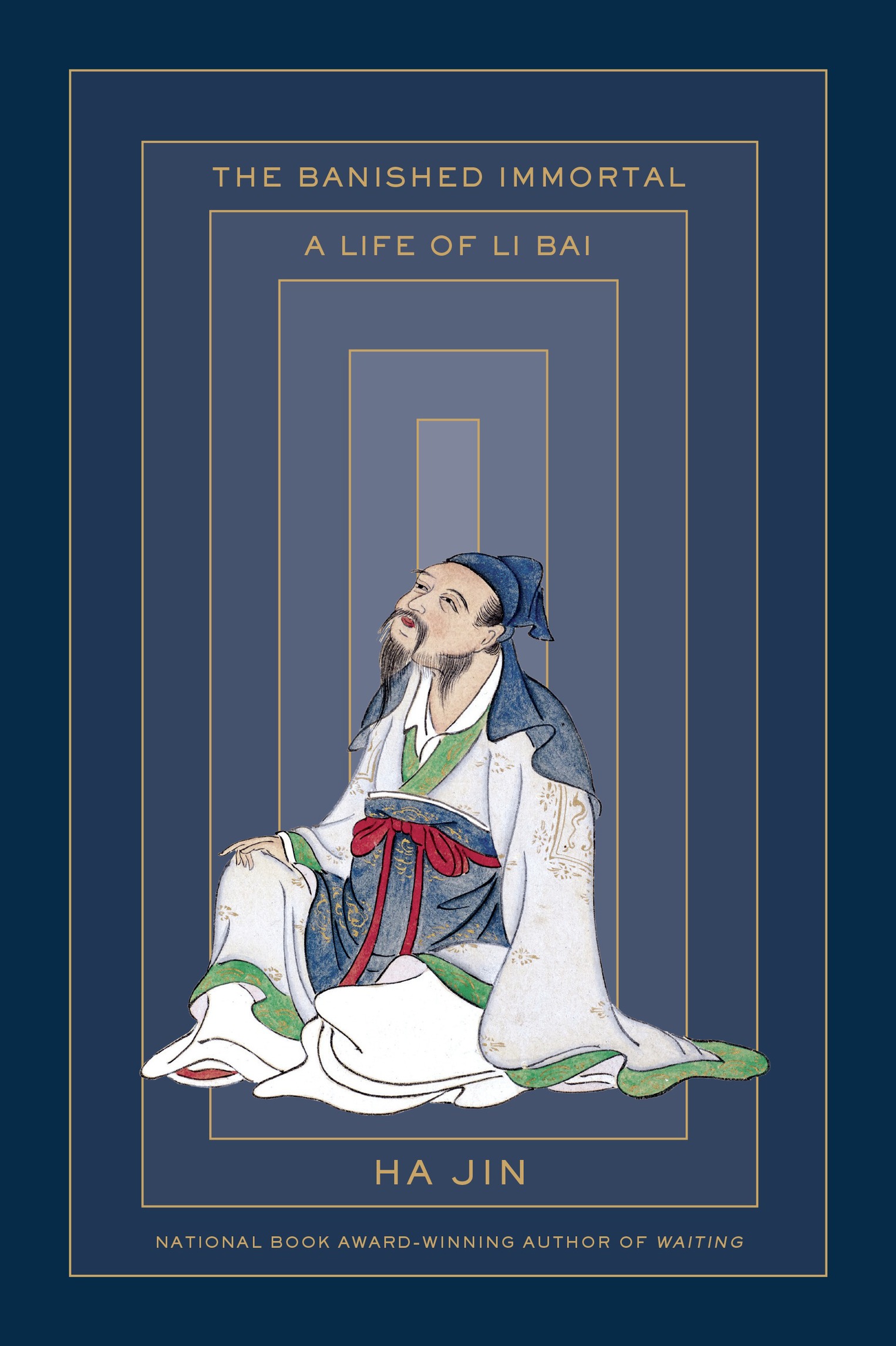

Cover image: Portrait of Li Bai British Library Board. All rights reserved/Bridgman Images.

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

v5.4_r1

ep

Contents

PRELUDE

He has many names. In the West, people call him Li Po, as most of his poems translated into English bear that name. Sometimes it is also spelled Li Bo. But in China, he is known as Li Bai. During his lifetime (701762 AD ), he had other namesLi Taibai, Green Lotus Scholar, Li Twelve. The last one is a kind of familial term of endearment, as Bai was twelfth among his brothers and male cousins on the paternal side. It was often used by his friends and fellow poets when they addressed himsome even dedicated poems to him titled For Li Twelve. By the time of his death, he had become known as a great poet and was called zhexian, or Banished Immortal, by his admirers. Such a moniker implies that he had been sent down to earth as punishment for his misbehavior in heaven. Over the twelve centuries since his death, he has been revered as shixian, Poet Immortal. Because he was an excessive drinker, he was also called jiuxian, Wine Immortal. Today it is still common for devotees of his poetry to trek hundreds of miles, following some of the routes of his wanderings as a kind of pilgrimage. Numerous liquors and wines bear his name. Indeed, his name is a ubiquitous brand, flaunted by hotels, restaurants, temples, and even factories.

In English, in addition to Li Po, he once had another pair of names, Li Tai Po and Rihaku. The first is a phonetic transcription of his original Chinese name, Li Taibai, the name his parents gave him. And Ezra Pound, in his Cathayhis collected translations of classical Chinese poetrycalled Li Bai Rihaku because Pound had translated those poems from the notes left by the American scholar Ernest Fenollosa, who had originally studied Li Bais poetry in Japanese when he was in Japan. Pounds loose translation of Li Bais The River-Merchants Wife: A Letter has been included in many textbooks and anthologies as a masterpiece of modern poetry. It is also one of Pounds signature poemsarguably his best known. For the sake of consistency and clarity, in the following pages let us stay with the name Li Bai.

He also has several deaths ascribed to him. For hundreds of years, some people even maintained that he had never died at all, claiming to encounter him now and then. In truth, we are uncertain about the exact date and cause of his death. In January 764, the newly enthroned Emperor Daizong issued a decree summoning Li Bai to serve as a counselor at court. It was a post without actual power in spite of its high-sounding title. Yet to any man of learning and ambition such an appointment was a great favor, a demonstration of the emperors benevolence and magnanimityand in Li Bais case, a partial restoration of the high status he had once held in the court. When the royal decree reached Dangtu County, Anhui, where Li Bai was supposed to be located, the local officials were thrown into confusion and could not find him. Soon it was discovered that he had died more than a year before. Of what cause and on what day, no one could tell. So we can only say that Li Bai, despite his renown, passed away in 762 without notice.

However, such an obscure death was not acceptable to those who cherished his poetry. They began to give different versions of his death, stories spun either to suit the romantic image of his poetic personality or to provide a fitting conclusion to his turbulent life. In one version, he died of alcohol poisoning; this was in keeping with his lifelong indulgence in drink. Another claims that he died of an illness known as chronic thoracic suppurationpus penetrating his chest and lungs. The first mention of this comes from Pi Rixiu (838883) in his poem Seven Loves: He was brought down by rotted ribs, / Which sent his drunken soul to the other world. Although there is no way we can verify this claim, it sounds crediblesuch a chest problem could have been caused by his abuse of alcohol. In his final years, Li Bais drinking and poverty would have aggravated his pulmonary condition. But the third version of his death is far more fantastic: in this version, he drowns while drunkenly chasing the moons reflection on a river, jumping from a boat to catch the ever-shifting orb.

Even though this scene smacks of suicide and is perhaps too romantic to be believed, it is the version that has been embraced by the publicin part because Li Bai, as his poetry shows, loved the moon. Even in his early childhood he was fixated on it. In his poem Night Trip in Gulang, he writes, As a young child, I had no idea what the moon was / And I called it a white jade plate. / Then I wondered if it was a mirror at the Jasper Terrace / That flew away and landed on top of green clouds. In Chinese poetry, Li Bai was the first to use the image of the moon abundantly, celebrating its loftiness, purity, and constancy. He imagined the moon as a serene landscape with sublime dwellings for xian, or immortals, who are often surrounded by divine fauna and flora and their personal pets. The beliefs of the ancient Chinese did not separate divinity from humanity, and their imagined heavenly space resembled the human world, with similar (but more fantastic) landscapes and architecture and creatures. If cultivated enough, any human being could rise to the order of divinity, becoming a xianmany temples in China worshiped these kinds of local deities. Heaven was inhabited by these beings, who were somewhat like superhumans, powerful and carefree and immortal.