A HEADPRESS BOOK

First published by Headpress in 2016

{e}

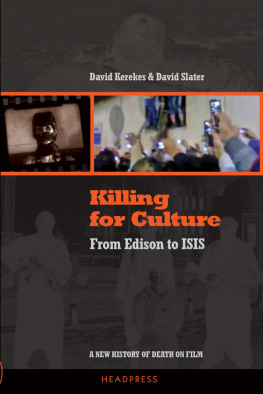

KILLING FOR CULTURE

From Edison to Isis: A New History of Death on Film

Text copyright David Kerekes & David Slater

This volume copyright Headpress 2016

Book cover, design & layout: Mark Critchell <>

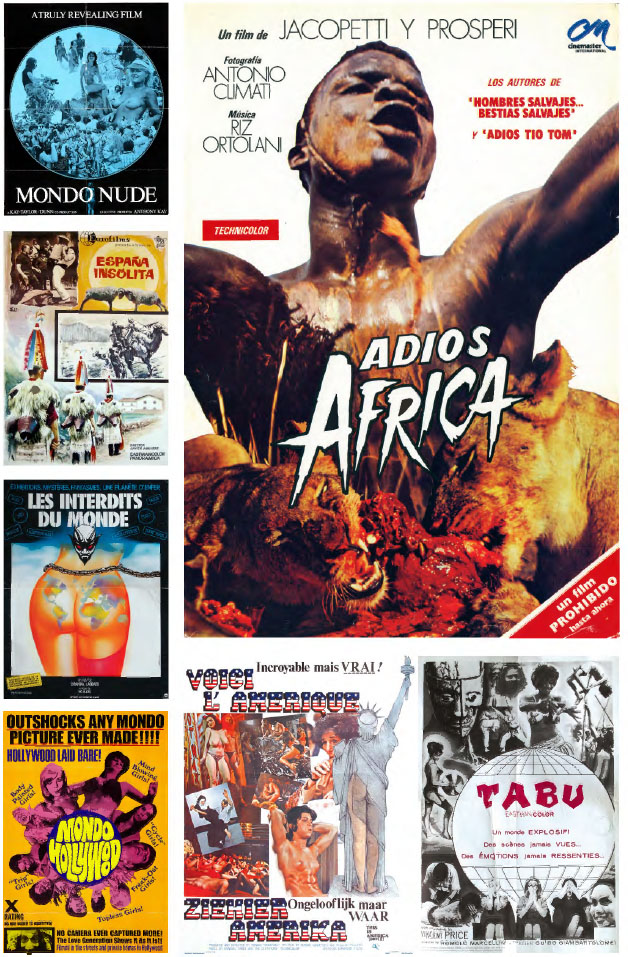

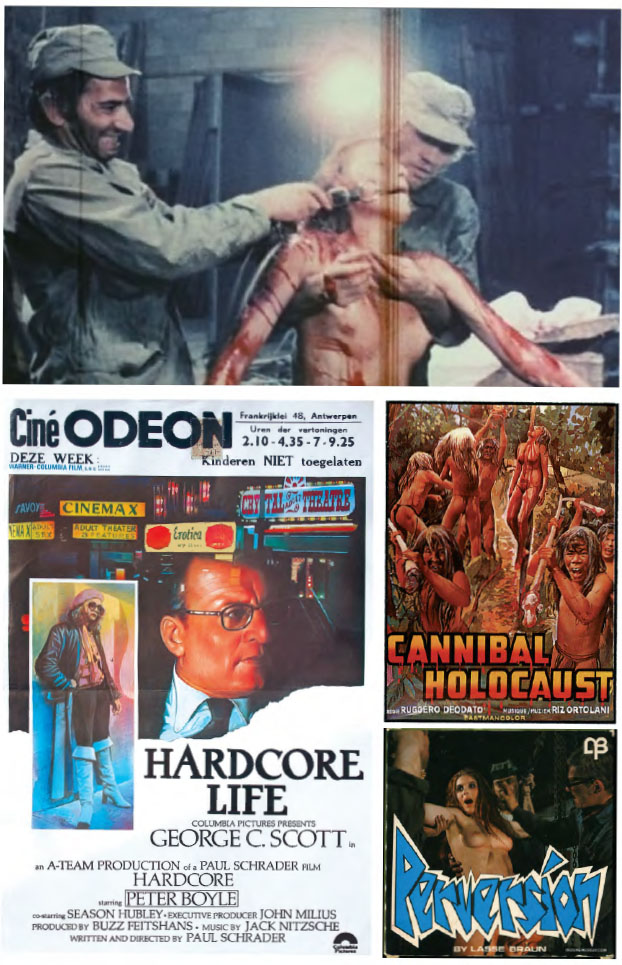

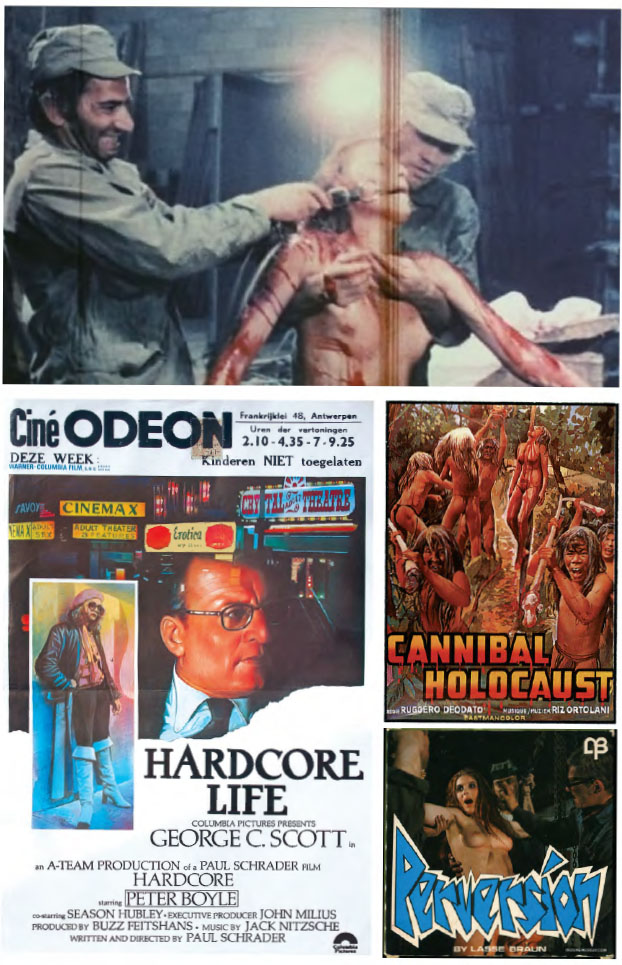

Cover images: (front) Scene from Hardcore (1978), public execution in Benghazi,

Lybia, c.2011; (back) Africa Addio (1966), Gut (2012)

Headpress diaspora: Thomas Campbell, Caleb Selah, Giuseppe, Dave T

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

All Rights Reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Images are used for the purpose of historical review. Grateful acknowledgement is given to the respective owners, suppliers, artists, studios and publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

978-1-909394-34-6 ISBN PAPERBACK

978-1-909394-35-3 ISBN EBOOK

NO-ISBN HARDBACK

Headpress. The gospel according to unpopular culture.

The NO-ISBN special edition hardback of this book, and other items, are available exclusively from World Headpress

WWW.WORLDHEADPRESS.COM

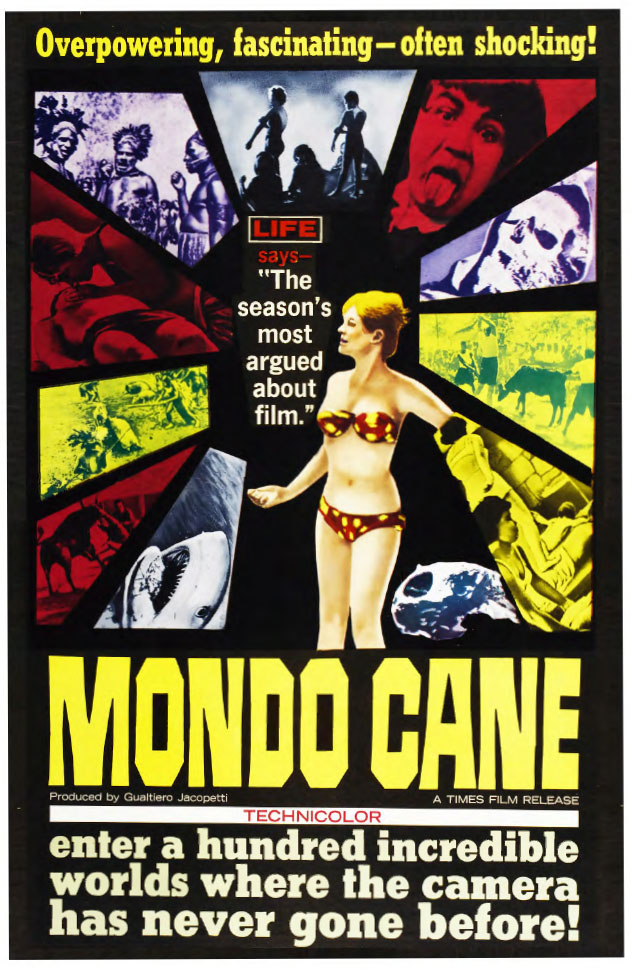

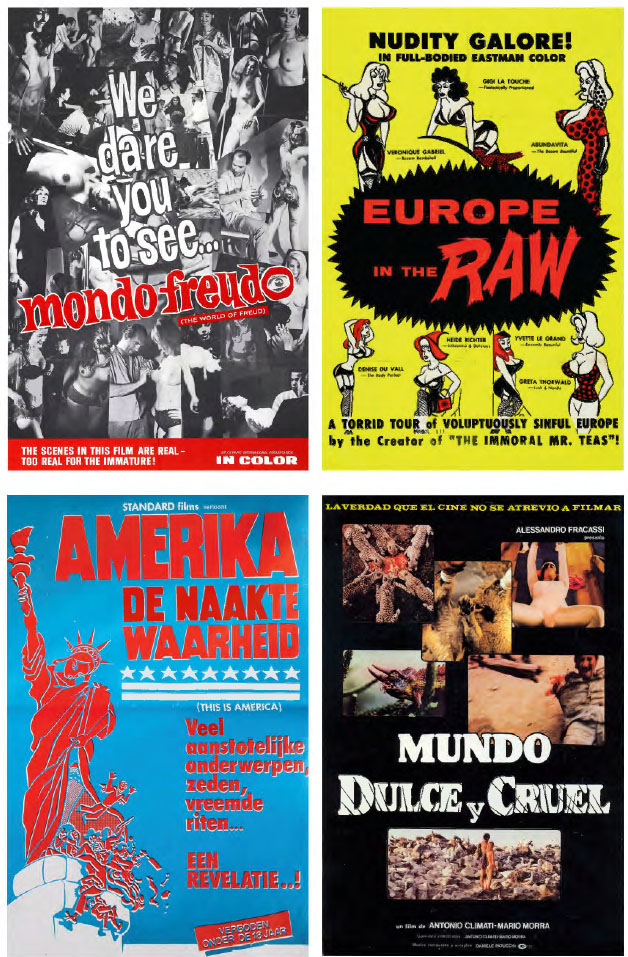

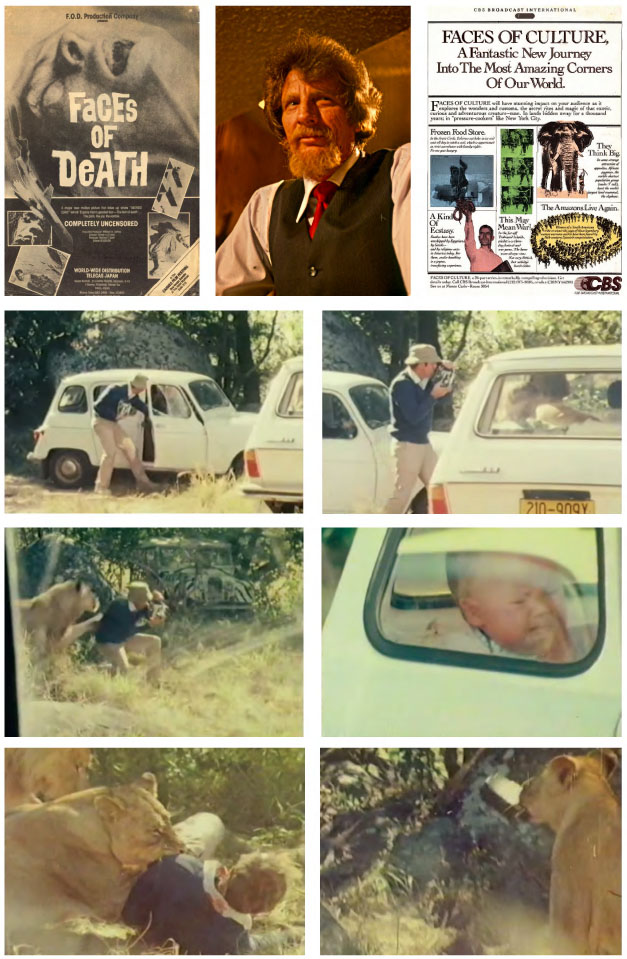

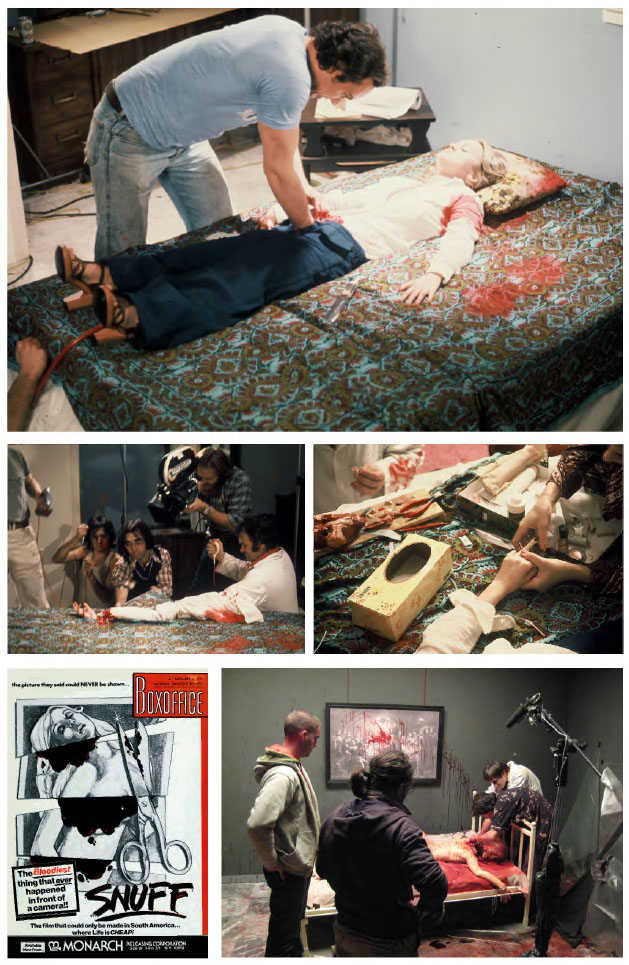

INTRODUCTION

T hroughout the history of film, a prurient imbalance has existed between observer and observed, driving the spools in the shadowy projection box. Since the dawn of cinema, images of death and destruction have run alongside the underground trade in explicit sex. At the turn of the nineteenth century, viewing boxes, such as the Kinetoscope, were found in penny arcades and dime museums, and any other place of leisure where crowds might gather. Popular testimony presents these peepshows as a form of vice, much as it would cinema that followed (and any form of popular entertainment after that). A crank of the handle provides the lone spectator with a saucy diorama, a woman dancing, perhaps. But it might also offer scenes depicting calamity or a public execution. Cecil M. Hepworths Explosion of a Motor Car (1900), for instance, is a blackly comic film in which the passengers of the titular vehicle are blown sky-high. A police officer assesses the damage and collects body parts when eventually they return to Earth. There is nothing comic about Execution of a Chinese Bandit (1904), however, a scene showing the actual beheading of a criminal outside Mukden, China.

There was also a vogue for period drama and the re-enactment of historic executions, with scenes of female subjects put to death among them. In Joan of Arc (1895) and The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895) we witness a grave comeuppance for two women of strength and character, perhaps indicative of attitudes toward the fledgling womens suffrage movement at the time of their production.

Both these films were made by Thomas Edison and his Edison Manufacturing Company. The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, at approximately eighteen seconds, is presented in the manner of a stage drama. The deposed monarch is brought to kneel at a chopping block in front of a small crowd (we have prime position) and her head unceremoniously lopped off with a swift blow of the executioners axe. The head (replaced by a facsimile) bounces to the floor, before being retrieved by the executioner and held aloft for the audience to see.

The ruthlessly entrepreneurial Edison, who has taken much credit for early cinema, produced many films of this stripe (essentially exploitation films). Like a proto-Andy Warhol, he didnt do an awful lot of filming himself. But it was his name on the flag. The Cock Fight (1894), which depicts two gamecocks fighting, proved so popular the film prints were all but ruined not uncommon for the time. In their place came Cock Fight no.2 (1894), effectively the same film with some elaboration: Two men goad each other and exchange bets behind the fighting birds, a white backdrop amplifying the action. Blood sports, including rat baiting, concedes historian Charles Musser, were popular early subjects for Edisons camera.

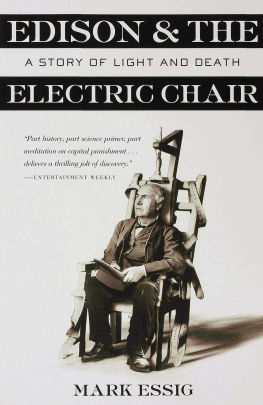

Another popular subject was electricity. Edison, the inventor of the lightbulb, worked competitively on methods of electric power distribution for many years. One result was the electric chair, created to demonstrate the potentially lethal nature of rival AC power compared to Edisons own DC supply. A film from 1901 covers a number of Edisons bases, The Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison. Leon Czolgosz was the assassin of US President William McKinley, shooting him twice with a pistol in Buffalo, New York, in September 1901. Czolgosz was tried, found guilty and sentenced to death, frying in the electric chair at Auburn prison the following month.

The three-minute film opens with slow panning shots of the concrete faade of the Auburn prison complex. Fabrication takes over when next we see an interior that represents the confines of the prison itself, with an actor playing the condemned man led to his death by guards. The actor is secured to the electric chair and surrounded by functionaries giving (silent) instructions. The switch is thrown, the man jerks several times and a doctor pronounces him dead.

Edison famously recorded the execution of a much larger mammal in Electrocuting an Elephant (1903), a further effort to promote his joint ventures of film and electricity. Topsy was a circus elephant that had grown tired of the life, killing three trainers and running amok. She was tried and sentenced to death. Edison, who often gave public demonstrations highlighting the ills of alternate current by killing small animals with it, now stepped in with a death apparatus that offered a greater marketing opportunity.

Electrocuting an Elephant is a film decayed with time, having the quality of a bad dream. It begins in an outdoor space with men leading the doomed animal toward the camera. Tethered, it then kicks a free foot in anger or fear. Plumes of smoke envelop the beast and finally it topples. Edison had wanted to film the genuine execution of Czolgosz at Auburn, but the authorities declined. Topsy is the alternative, the next-best shot. Had his request been successfully met, Edison would undoubtedly have had a tidy package on his hands. He toured

Next page