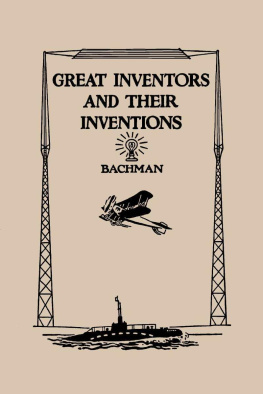

All rights reserved. No part of this book shell be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or by any information or retrieval system, without written permission form the publisher.

A. RUSSELL BOND

PREFACE

T he great World War was more than two-thirds over when America entered the struggle, and yet in a sense this country was in the war from its very beginning. Three great inventions controlled the character of the fighting and made it different from any other the world has ever seen. These three inventions were American. The submarine was our invention; it carried the war into the sea. The airplane was an American invention; it carried the war into the sky. We invented the machine-gun; it drove the war into the ground.

It is not my purpose to boast of American genius but, rather, to show that we entered the war with heavy responsibilities. The inventions we had given to the world had been developed marvelously in other lands. Furthermore they were in the hands of a determined and unscrupulous foe, and we found before us the task of overcoming the very machines that we had created. Yankee ingenuity was faced with a real test.

The only way of overcoming the airplane was to build more and better machines than the enemy possessed. This we tried to do, but first we had to be taught by our allies the latest refinements of this machine, and the war was over before we had more than started our arial program. The machine-gun and its accessory, barbed wire (also an American invention), were overcome by the tank; and we may find what little comfort we can in the fact that its invention was inspired by the sight of an American farm tractor. But the tank was a British creation and was undoubtedly the most important invention of the war. On the sea we were faced with a most baffling problem. The U-boat could not be coped with by the building of swarms of submarines. The essential here was a means of locating the enemy and destroying him even while he lurked under the surface. Two American inventions, the hydrophone and the depth bomb, made the lot of the U-boat decidedly unenviable and they hastened if they did not actually end German frightfulness on the sea.

But these were by no means the only inventions of the war. Great Britain showed wonderful ingenuity and resourcefulness in many directions; France did marvels with the airplane and showed great cleverness in her development of the tank and there was a host of minor inventions to her credit; while Italy showed marked skill in the creation of large airplanes and small seacraft.

The Central Powers, on the other hand, were less originative but showed marked resourcefulness in developing the inventions of others. Forts were made valueless by the large portable Austrian guns. The long range gun that shelled Paris was a sensational achievement, but it cannot be called a great invention because it was of little military value. The great German Zeppelins were far from a success because they depended for their buoyancy on a highly inflammable gas. It is interesting to note that while the Germans were acknowledging the failure of their dirigibles the British were launching an airship program, and here in America we had found an economical way of producing a non-inflammable balloon gas which promises a great future for arial navigation.

The most important German contribution to the warit cannot be classed as an inventionwas poison gas, and it was not long ere they regretted this infraction of the rules of civilized warfare adopted at the Hague Conference; for the Allies soon gave them a big dose of their own medicine and before the war was over, fairly deluged them with lethal gases of every variety.

Many inventions of our own and of our allies were not fully developed when the war ended, and there were some which, although primarily intended for purposes of war, will be most serviceable in time of peace. For this war was not one of mere destruction. It set men to thinking as they had never thought before. It intensified their inventive faculties, and as a result, the world is richer in many ways. Lessons of thrift and economy have been taught us. Manufacturers have learned the value of standardization. The business man has gained an appreciation of scientific research.

The whole story is too big to be contained within the covers of a single book, but I have selected the more important and interesting inventions and have endeavored to describe them in simple language for the benefit of the reader who is not technically trained.

A. Russell Bond

New York, May, 1919

CHAPTER I The War in and Under the Ground

F or years the Germans had been preparing for war. The whole world knew this, but it had no idea how elaborate were their preparations, and how these were carried out to the very minutest detail. When the call to arms was sounded, it was a matter of only a few hours before a vast army had been assembledfully armed, completely equipped, ready to swarm over the frontiers into Belgium and thence into France. It took much longer for the French to raise their armies of defense, and still longer for the British to furnish France with any adequate help. Despite the heroic resistance of Belgium, the Entente Allies were unprepared to stem the tide of German soldiers who poured into the northern part of France.

So easy did the march to Paris seem, that the Germans grew careless in their advance and then suddenly they met with a reverse that sent them back in full retreat. However, the military authorities of Germany had studied not only how to attack but also how to retreat and how to stand on the defensive. In this, as in every other phase of the conflict, they were far in advance of the rest of the world, and after their defeat in the First Battle of the Marne, they retired to a strong position and hastily prepared to stand on the defensive. When the Allies tried to drive them farther back, they found that the German army had simply sunk into the ground. The war of manuver had given way to trench warfare, which lasted through long, tedious months nearly to the end of the great conflict.

The Germans found it necessary to make the stand because the Russians were putting up such a strong fight on Germany's eastern frontier. Men had to be withdrawn from the western front to stem the Russian tide, which meant that the western armies of the kaiser had to cease their offensive activities for the time being. The delay was fatal to the Germans, for they had opposed to them not only brave men but intelligent men who were quick to learn. And when the Germans were ready to resume operations in the West, they found that the Allies also had sunk into the ground and had learned all their tricks of trench warfare, adding a number of new ones of their own.

.jpg)

www.facebook.com/EKitapProjesi

www.facebook.com/EKitapProjesi