Copyright 2019 Owen W. Cameron

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire, LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1838596 736

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For my parents

Contents

Foreword

On 19 th August 1978, in the small Iranian town of Abidan on the edge of the Persian Gulf, a tired old cinema began the screening of a popular local film called The Deers . Within the hour, four men had blocked the exits, set fire to the cinema, and sealed the fates of more than 400 people trapped inside.

Mixing solvent and vegetable oil in soft drink bottles, they each bought a ticket, shared a seat in the crowded balcony of the Rex Cinema, and waited for fifteen minutes to slip out and stoke a flank of flames that would link up the lobby, corridors and the main stairs.

So much of that summer night echoed the 1970s: on the drawbridge between the crumbling, unregulated past and the modernity we inhabit today. Abidan possessed the best trained civil fire brigade in Iran, but it counted for little when the janitor and cinema staff couldnt work the fire extinguishers and fled the scene. The wooden walls were clad in a polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a petrochemical by-product that the industrial town made more than it knew what to do with. Almost certainly more died in their cinema seats from smoke inhalation and the burning PVC gases than the fire itself.

Only hours earlier, the four arsonists had eaten liver kebabs at a local food stand and driven around town looking for a cinema on a Saturday night seemingly like young men from any city in the world. With one failed attempt due to a poor solvent mixture, and another ticket office shut, they finally found the Rex and tried to raze the picture theatre to the ground.

Abidan had been a British oil town from the days of the earliest discoveries in the twentieth century; an alluvial island flanked by rivers on every side, with palm groves that helped to weather the brutal summer temperatures. Yet in the anarchy of the few days after the cinema fire, rumour and conspiracy theories engulfed the city and the nation.

Many locals suspected the new police chief had ordered the side fire exits to be bolted shut. A woman who escaped saw no bolts on the door, and many today believe the doors were opened inwards due to a design flaw.

In the din of Abidans grief, the truth in the years after the event mattered for little. A judge in 1980 condemned the elderly owner of the Rex (away in Tehran at the time), the cinema manager and several police officers all to death. Another wild theory alleged fire trucks were deliberately sent with no water; several firefighters were sent to jail, despite their efforts to tear down the cinemas west wall and save whomever they could.

The actions and response to the Abidan cinema fire laid bare Irans simmering anger it was a nation wrestling with a deep fragility it did not know how to repair or resolve. In that same month of August 1978, an infamous CIA assessment from the Tehran Station to the Carter Administration stated that Iran is not in a revolutionary or even a pre-revolutionary situation. Within a year, events would turn the Middle East on its head, and continue echoing around the world for the rest of the twentieth century, even to the present day.

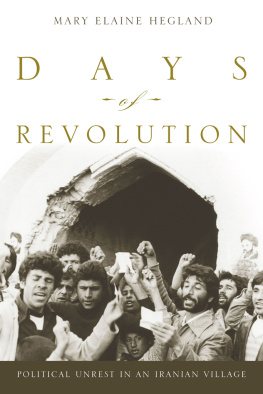

Revolutions are nothing new. They come from nowhere, and in a matter of days or weeks they have wrought their own course. Over time, they fossilise into history books and family legends. But to live through one, to know that raw upheaval and watch life change in terrifying, uncontrollable ways what is that like?

The unprecedented extremism of the 1979 Iranian Revolution is only really comparable to its French and Russian equivalents two events that now stand like totem poles in world history, taught to schoolchildren all over the globe.

Some years in the last hundred have taken on an iconic resonance in our collective memory: 1914, 1929, 1939, 1945, 1989. In contrast, 1979 does not quite join that company; yet there was very much a sense that those who rose to power in that calendar year Margaret Thatcher, Pope John Paul II, Deng Xiaoping and Ayatollah Khomeini were going to the shape the world.

In 1976, all of them were in relative obscurity. Thatcher was a failed British Education Secretary. The future Pontiff was the Archbishop of Krakow. Deng was an outcast Chinese politician removed from all formal positions. And Khomeini was an exiled cleric, preaching a puritan version of Islam that enjoyed little support anywhere. After the Revolution, Khomeinis actions shaped Americas hand in the Middle East, and recast the daily existence of tens of millions of people. Yet within a single generation, the average Westerner knows so little about 1979.

For the most unusual of reasons, I have been a fortunate exception. Why? Because my parents lived through it all. In the crosswinds of the mid-1970s, an Australian mining engineer and a Scottish nurse took two strange foreign assignments, relocated to the famous old heart of Persia, and met one night over expat drinks. They fell in love, then found themselves amid the surveillance, explosions, rallies and riots of a nation tearing itself apart. History changes at a pace those living through it are seldom able to grapple with. It is a lesson that continues to be relevant, and one that shaped my parents lives forever.

The events of the world most vividly come to life when we are connected to the journeys of individuals. For that reason, this book is both the history of those times and a personal record. My motive to write comes from knowing the end to this tale, and the incredible events that led to my parents escape.

I hope some will read this eager to know why 1979 rocked the world, and how a storied, eclectic nation like Iran slipped silently behind a curtain; one that many of us have never peered beyond or understood since. But much more than this, I chronicle my parents days of the revolution for the children and grandchildren I am yet to have so they stride into the world knowing how lucky we all are to be here, how life and death are fickle absolutes, and how the world is more impulsive and fragile than we would ever wish to admit.

The Birthday Ballot

On a late evening in March 1966, the car engine hummed, motionless by a quiet bush roadside. It was a turquoise 1956 FJ Holden, the epitome of post-war Australian car-making. The radio crackled with voices and music and the clock counted down to the moment of truth. Leslie John Woolcock sat quietly in his most prized possession and trembled. With a cigarette in hand and the window down, he waited for the verdict.