To Phoebe, our North Star

Preface

T here are, I suppose in my ignorance, two foolproof ways to find out if a newly built wooden boat is watertight. One is to put it in the water and see if it sinks. The other is to keep it on dry land, fill it with water, and see if it leaks.

Superficially, Method A, drawing on centuries of tradition and accompanied by the obligatory champagne and all-who-sail-in-her brouhaha, is the most attractive option, especially if one is fond of attention. But it does have its drawbacks. The most obvious of these is that such a public ceremony, fairly quivering as it does with the potential for massive hubristic blowback, demands that the shipwright has complete confidence in his or her skills. It is a moment of supreme, absolute truth.

By contrast, Method B, practiced in absolute privacy, not only excludes all witnesses to possible failure but also gives the craven boatbuilder the opportunity to correct any fault, or multiple faults, before brazenly resorting to the pomp and ceremony of Method A, as though nothing untoward has occurred.

But for the brave of heart, for the plucky, audacious, damn-the-torpedoes type of swashbuckling adventurer, there is no Method B, only the pure path of Method A. Method B, an undignified, wretched betrayal of centuries of tradition, is to be despised. It is a dark surrender, reserved solely for the faint of heart, the weak of will, the timid what!-there-are- torpedoes ? type, lacking in all confidence, skills, and valor.

Which is why I am now standing here, heart in mouth, hose in hand....

1

Dear Phoebe ...

Grab a chance and you wont be sorry for a might-have-been .

Arthur Ransome, We Didnt Mean to Go to Sea

AUGUST 16, 2016

L ooking back, I suppose that at the time the decision to build you a boat must have seemed like a really terrific idea. Did I pause, even for a moment, to consider whether your daddya soft-handed, deskbound modern man with few tools, limited practical abilities, and an ignominious record of DIY disastercould possibly master the necessary skills?

More than two years on, its hard to remember. But I do know that in the weeks and months after you were born I found myself in a strange, unfamiliar place. Oddly, perhaps, I wasnt worried about the challenges of raising a child at my age. But, as I paced the floor night after sleep-deprived night with this inexpressibly precious new life in my arms, my mental compass swung wildly from emotionally charged elation to morbid musings about your future andas a father, for the second time, at fifty-eightmy chance of playing much of a part in it.

This wasnt an entirely unfounded concern. In February 2012, after suffering mild chest pains while running, I underwent a wholly unexpected multiple coronary artery bypass operation in a hospital in Dubai, where I was working as a journalist. So much for a lifetime of not smoking, always eating and drinking sensibly, and exercising regularly obsessively , some might say. Rowing, running, swimming, triathlonsall had played a major part in my life, and in my idea of who I was. But none of it, it seems, had been sufficient to defuse the ticking time bomb of familial hypercholesterolemia, a genetic defect that starts lining the arteries with gunk from an early age. This perhaps explains why Bert, your maternal great-grandfather, died in 1946 with a coronary thrombosis at the age of fifty, despite years of rationing that would have severely limited his intake of heart-stopping foods. Thanks to a South African surgeon and the modern miracle of statins, I already have more than a decade on him.

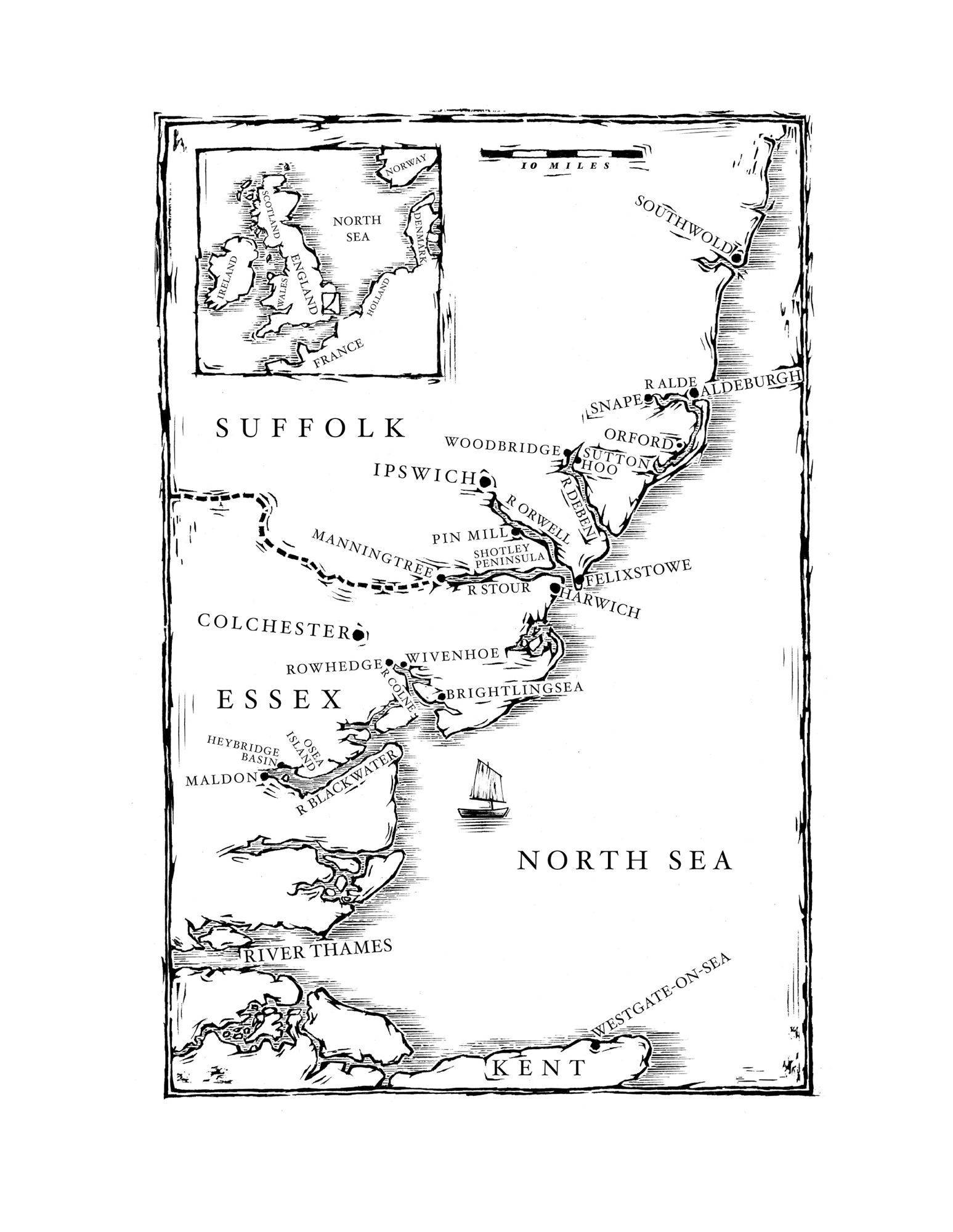

Undergoing bypass surgery hurts more than somewhat, and for months afterwards. Having your chest cracked from throat to sternum and yards of vein yanked out of your legs is, I guess, always going to sting a little. But though unforgettable, a bypass is also survivable, especially if you go through it when youre fit and youngish, which, at fifty-six, I was. So perhaps there was a point to all that rowing, running, swimming, etc. Twelve weeks later, I was back in England andcautiously at firstrunning in the late-spring sunshine along a Suffolk riverbank. It was one of those days when it really did feel good to be alive.

But it was your appearance, two years and two months after the operation, that really gave me the opportunity to make the most of my new lease on life. It was also a kind of second chance. I have a son, Adam, from my first marriage, and he has two sons of his ownyou know them as your nephews, seven and eight years older than you. They know you as Auntie Phoebe and me as Granddad Jonny. Modern families.

The good news for you is that this time around Daddy plans to be much better at the whole fatherhood thing. I was an immature twenty-one when I married Adams mother, and a not-much-more-mature twenty-six when he was born, in 1981. I remember pacing the floor with him in my armsjust like you, it was the only way he would sleepbut I recall very little else from those days. His mother and I split up when he was about two, and Adam spent most of his early life overseas with her. Im ashamed to say that at the time that seemed like some kind of liberation. Apart from the occasional holiday, I saw very little of Adam until he came to live with me in England when he was fifteen.

At some point in the thirty-six years since Adam was born I must finally have grown up, because from the moment I first met you the thought of not seeing you for a single day, let alone for months on end, was inconceivable. And the thought of having turned my back on my two-year-old son all those years ago filled me with deep shame and regret.

But alongside the massive dose of unconditional love that flooded my entire being the day you were born, and can still unexpectedly move me to tears without warning, I became aware of another new sensationfear.

Id never feared the bloke with the scythe previouslynot while struggling to keep my head above water mid-Atlantic, or even while going under the surgeons knife in Dubai. But now that my life was suddenly and utterly about something other than merely me, fear him I didespecially after it dawned on me that, if I lived that long, Id be seventy years old by the time you started secondary school.

Sorry, darlingkids can be cruel. But you, I already have no doubt, are going to be smart enough, and tough enough, to deal with all of that. Though if you prefer, Ill happily drop you off round the corner from the school gates.

At what age do children begin banking memories they retain for life? Experts aresurprisedivided on the question; guesstimates range from three and a half to six years old. Either way, I know that one day, and sooner rather than later, I shant be there for you. How, then, to reach out across time to remind you that you had a daddy who loved you unconditionally and who wanted nothing more out of what was left of his life than to equip you to make your way through yours with wisdom, courage, compassion, and imagination?

I could, I suppose, have simply written you a letter, or recorded a video for you to watch on your smartphone when youre older. I rehearsed both in my head, many times, but struggled to strike a tone located acceptably between flippant brave face and sentimental self-pity.