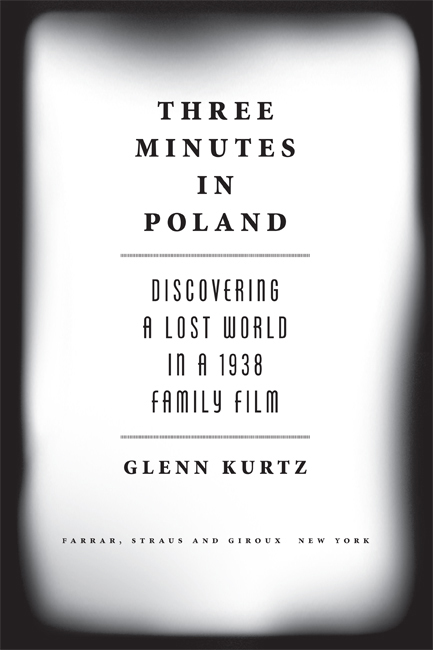

Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For the people we have lost

CONTENTS

[The gale] swept the squares clean, leaving behind it a white emptiness in the streets; it denuded the whole area of the marketplace. Only here and there a lonely man, bent under the force of the wind, could be seen clinging to the corner of a house.

BRUNO SCHULZ, The Gale

IN THE SUMMER of 1938, my grandparents David and Liza Kurtz sailed from New York to Europe for a six-week summer vacation. Together with three friends they visited England, France, Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, and, passing through Germany, they made a side trip to Poland, where both my grandparents were born.

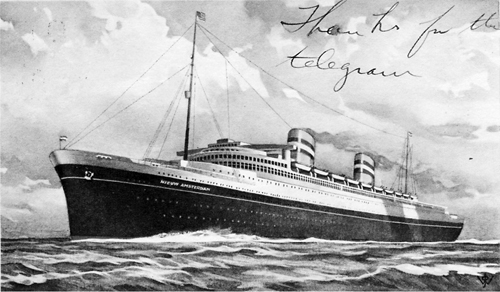

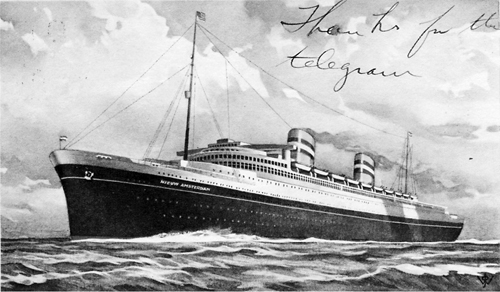

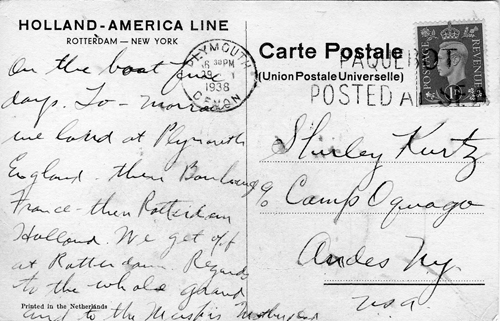

Im holding a postcard from this trip that my grandfather sent to his daughter, my aunt. The card shows a painting of the Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam crossing a green-black sea. Spray at the ships waterline and whitecaps on the waves give the impression of motion. The black hull and white Art Deco superstructure gleam against clouds tinged with pink and blue. Smoke ribbons from twin yellow smokestacks. A bird trails off the stern.

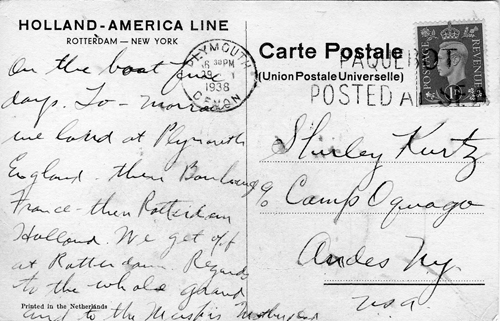

On the reverse side, my grandfather writes, On the boat five days. Tomorrow we land at Plymouth, England, then Boulonge, France [he misspells Boulogne]then Rotterdam, Holland. We get off at Rotterdam.

My aunt Shirley Kurtz Mandel produced this postcard three years after I first asked what she knew about her parents 1938 trip to Europe. The manila envelope containing this and about thirty other postcards and letters from David and Liza had been stuffed in a box of unrelated papers, forgotten for more than half a century. Shirley rediscovered it in late 2011 when, after sixty-three years, she moved out of her New York apartment.

One year after my grandparents vacation, Europe would be at war. On September 1, 1939, the German army overran Poland, and within a few years, with terribly few exceptions, the Jewish inhabitants of the Polish towns my grandparents had visited would be murdered.

But David and Liza Kurtz could not foresee the future. My grandparents and their friends were tourists, relatively prosperous American tourists, blissfully unaware of the catastrophe that lay just ahead. They rode across Europe with trunks of clothing, stayed at five-star hotels, shopped, and admired the sights. They visited art galleries and cathedrals, they strolled in the Jardin Exotique overlooking the old city of Monaco, they rode a small-gauge railroad through the Swiss Alps to the highest train station in Europe, the Jungfrau. Like tens of thousands of other Americans in the summer of 1938, my grandparents toured Europes grand attractions for their own pleasure.

The postcard my grandfather sent to his daughter has an English one-pence postage stamp with the cancellation Paquebot Posted at Sea. It is postmarked Plymouth, Devon, 29 July 1938, 6:30 p.m. From this, I learn the date of my grandparents departure, July 23, 1938, and that slender fact opens onto a wealth of period detail, giving me for the first time a glimpse at the scene as my grandparents begin their voyage.

Rains Delay Sailing of Nieuw Amsterdam, reported the New York Times the day after their embarkation. The Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam, under command of Captain Johannes Bijl, commodore of the line, sailed from her Hoboken pier forty minutes behind schedule after awaiting the arrival of four passengers from Philadelphia who had been delayed by a washout on the highway. The four Philadelphians, all prominent socially, according to the Times , had called ahead from Plainfield, New Jersey, when the road north was hidden by swirling water. The Nieuw Amsterdam was a stylish new ship. Its maiden voyage in May 1938, two months earlier, had been celebrated with lavish coverage in newspapers and magazines. This departure was less glamorous, the return leg of the ships fourth round trip, but still worth a few column inches devoted to society gossip. A July 23 piece in the Times entitled Ocean Travelers noted that Mrs. Adam L. Gimbel, Mrs. Mary van Renssalaer Thayer, and Mr. and Mrs. John B. Ballantine would be among the 850 people on board when the ship finally sailed under cloudy skies that Saturday. The Washington Post considered it newsworthy to report Mr. and Mrs. E. C. Rick will sail on the Nieuw Amsterdam this month for an extended tour in England, France, Switzerland and Italy. They will visit the Empire Exposition in Glasgow, Scotland, and later they will stop at Oxford to attend lectures at the university.

Mr. and Mrs. David Kurtz of Flatbush, Brooklyn, are not mentioned in the newspapers. They were comfortable but not prominent socially. Their travel plans concerned only the immediate family, and as a result, tracing their movements through Europe in the summer of 1938 has proved to be a challenge. I have been trying to determine their precise date of departure and the name of the ship for years. I know it now only because my aunt happened to save this postcard.

I would never have known about my grandparents trip at all or felt compelled to spend years trying to unearth its details had David and Liza not brought home a unique memento of their travels, which also happened to survive. On this vacation, my grandfather carried a 16mm home movie camera. He shot fourteen minutes of black-and-white and Kodachrome color film. He captured scenes of the ocean crossing and of a ferry ride in Holland. He filmed my grandmother and their friends walking in the Grand Place in Brussels, sunning themselves on the Mediterranean coast near Cannes, feeding pigeons in a Parisian park. And he documented three minutes of their visit to Poland, footage of ordinary life in a small, predominantly Jewish town, one year before the outbreak of World War II.

More than seventy years later, these few minutes of my grandfathers home movie would transform their summer vacation into something of lasting, even of historical, significance. Through the brutal twists of history, my grandfathers travel souvenir became the only surviving film of this Polish town. Eventually, his home movie would become a memorial to its lost Jewish community and to the entire annihilated culture of Eastern European Judaism.

What moments are worth recording? Which stories and memories are passed down, and which are lost? How much detail is preserved in the few artifacts that happen to survive? And how close can these artifacts bring us to the people who left them behind? These questions have haunted and surprised me in the years since I discovered my grandfathers 1938 film.

* * *

The postcard my grandfather sent from the Nieuw Amsterdam at the start of this voyage is addressed to Shirley Kurtz at summer camp in Andes, New York. Above the ship, where the clouds are darkest gray and most roseate pink, David has written, Thanks for the telegram. The telegram has not survived. My grandfathers message is only two sentences long. After briefing his daughter on their itinerary, he concludes, Regards to the whole grand and to the Mirskys. Mother and Dad. My aunt Shirley, now ninety-two, was sixteen years old in July 1938. She has fond memories of Camp Oquago for girls, which had opened just a few years before and was in business until 1993. The Mirskys, she tells me, were the camps owners. She remembers that Mr. Mirsky had a thick Yiddish accent. But she has no idea who or what the whole grand is. We puzzle over the word, trying to make it gang or group or crowd. But it says the whole grand. It might refer to a sports team or to her bunkmates at camp. Its possible my grandfather made a slip of the pen. Well never know. Unlike the missing telegram, these words have been preserved. But their meaning is lost.