John Mead Gould spent a single day at Antietam. The battle consumed him for the rest of his life.

On September 17, 1862, Gould fought on the Union side as a lieutenant with the 10th Maine. Pandemonium reigned in the close confines of the Western Maryland valley where the battle took place. So many soldiers fired so many weapons with such urgency that the field was soon shrouded in smoke. The air swam thick with projectiles; the sheer volume of noise was overwhelming. Cannon rumbled; bullets zinged. There were the shrieks of falling men, the whinnies of falling horses.

it was to get killed or wounded that day.

until the end of the Civil War.

married and raised three children. He taught in Sunday school, amassed a collection of buttons. Antietam never strayed far from his thoughts.

He wrote letters to his fellow Union soldiers, seeking to plumb their memories, hoping to resolve lingering mysteries. What enemy regiments had fired on his Maine boys on that fateful day? What were the exact spots where his various comrades went down? Where did General Mansfield fall?

, a testament to changing times, the passage of the years. On another visit, he stayed for an entire week, ceaselessly walking the field, trying to make sense of that now-distant day.

lie awake at night, he once stated.

, the same one hed lived in as a boy. Although seven decades removed from Antietam, hed ever remained in its thrall.

Gould was far from alone in his obsession. After all, he was only one among the multitude who fought at Antietam; many a man would relive this day for the rest of his years. This particular battle was simply different from others: more heated, more savage, more consequential.

men. This dwarfed everything that had come before. Such landmark Revolutionary War battles as Saratoga and Yorktown routinely resulted in fewer than 100 deaths among the Colonials. The entire War of 1812 (which, belying its name, stretched over nearly three years) produced 2,200 US fatalities, a lower number than occurred during a mere twelve hours at Antietam. Even such days of infamy as Pearl Harbor and September 11 saw fewer Americans killed.

himself Prest of the U.S., panicked a New Yorker. The last days of the Republic are near.

Even if an attack on a major city didnt immediately follow, a Confederate victory promised to create havoc in the North, politically and otherwise. The Rebel plan was to sow chaos and more chaos, though some of the ploys were remarkably subtle. For example, a Union loss at Antietam might prompt skittish Northerners to vote Lincolns Republican Party out of Congress. In would sweep the Democrats, a conservative party circa 1862, and one that might be more amenable to a negotiated settlement of the war. Perhaps a Democrat-controlled Congress would bypass Lincoln, inviting the Confederacy to rejoin the Union, slavery intact. Its no accident that Antietam happened in September: a primary goal was to disrupt the Unions midterm elections, only weeks away.

But this represented only one in a range of possible bad outcomes envisioned by the Rebels. By invading Maryland, the Confederacy had cooked up a diabolically clever scheme. Victory at Antietam promised to open up a number of different routes to the same outcome: an end to the war, substantially on Southern terms.

.

The stage was set for an epic showdown.

Ive chosen to tell this story in a different way, avoiding minutely detailed descriptions of troop movements (a standard feature of so many battle accounts) in favor of rendering a larger picture.

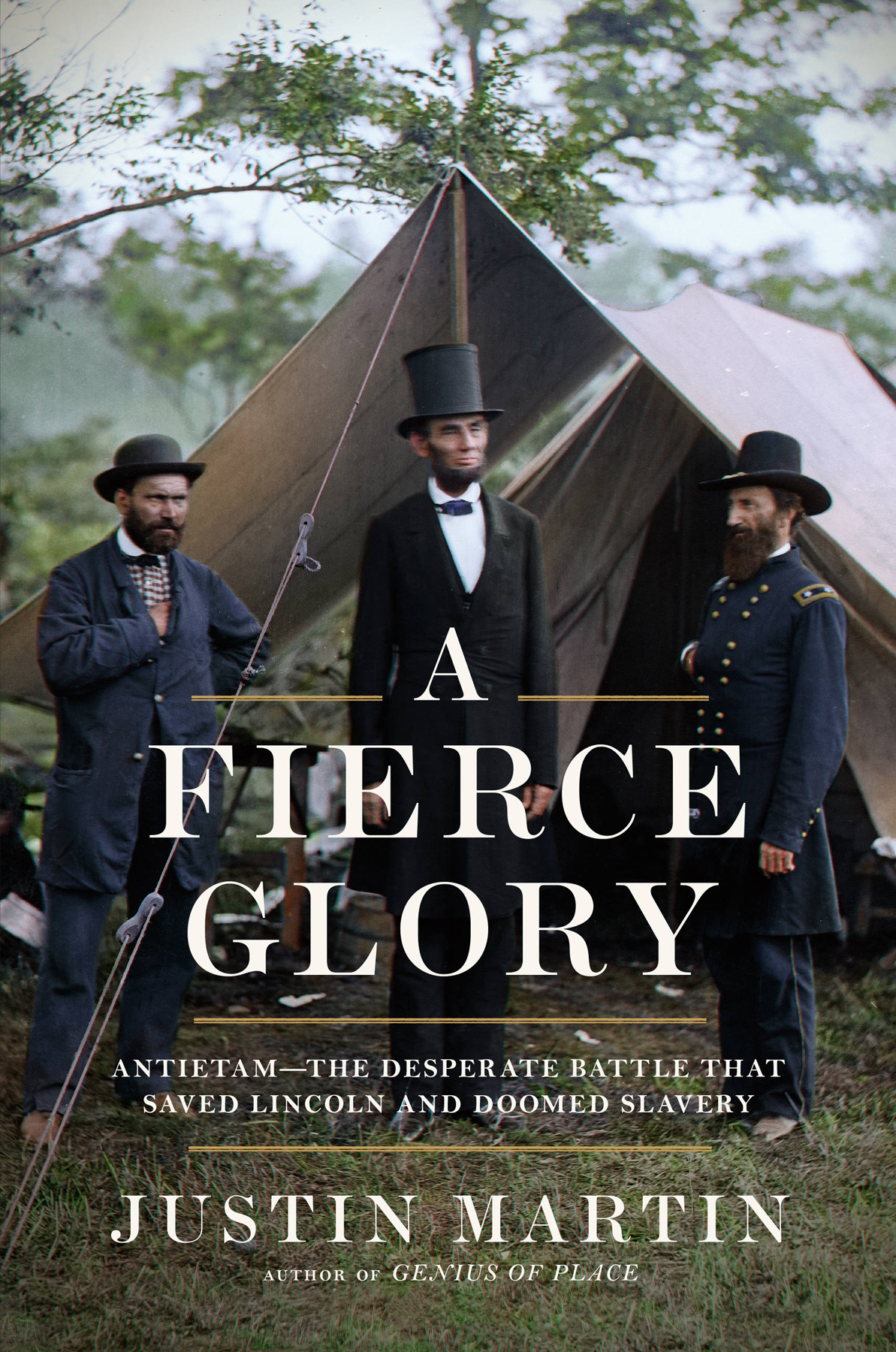

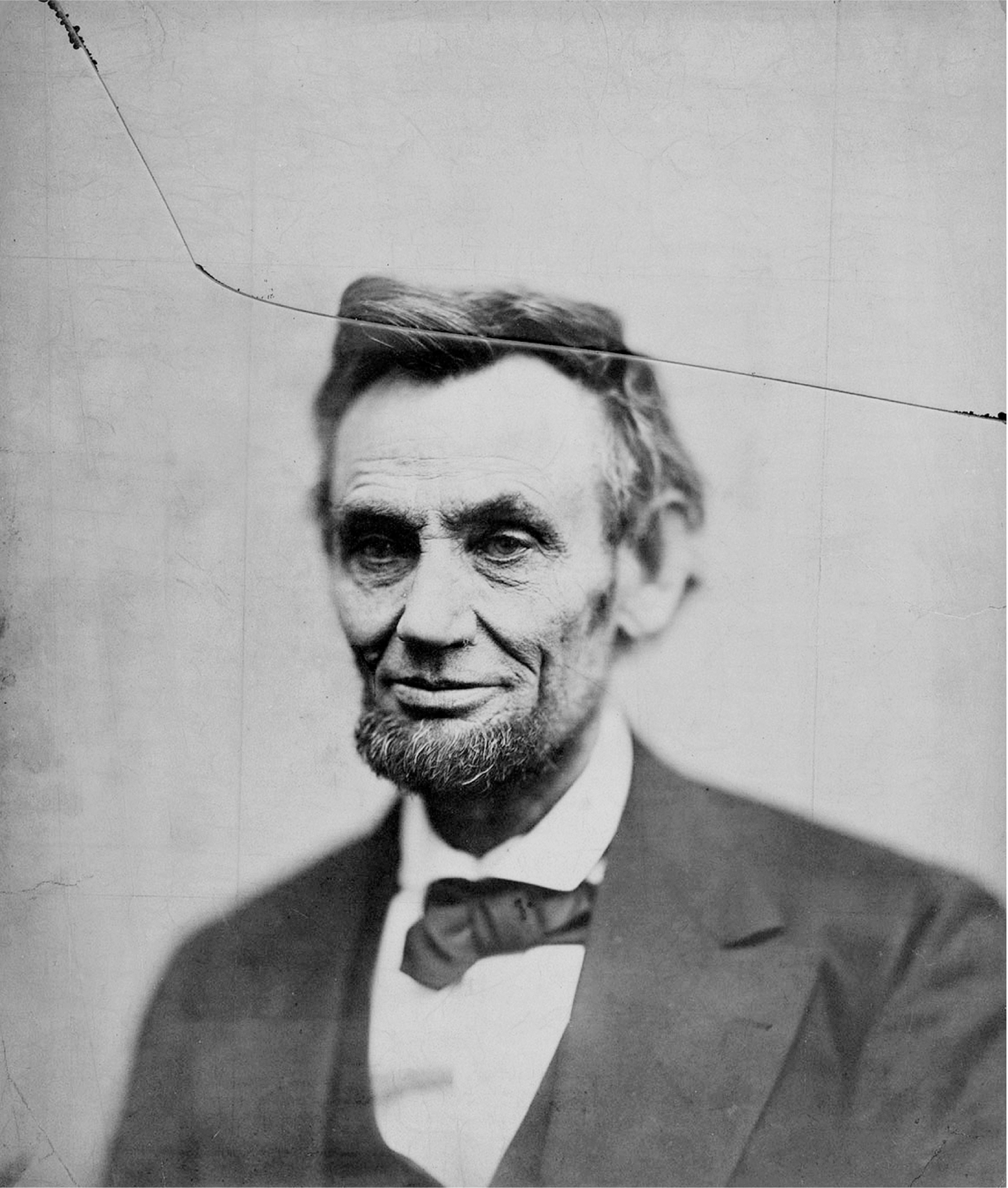

As such, Ive also chosen to weave Lincoln more deeply into the narrative. Existing Antietam titles tend to go light on Lincoln. After all, the president was in Washington during the fightingoffstage, as it were. Nevertheless, he anxiously awaited news, any news, out of Western Maryland. If the Union somehow eked out a victory, managed to break its losing streak, Lincoln was prepared to play that final card, issuing his Emancipation Proclamation. Declaring enslaved people free in the regions still in rebellion could be expected to shake the Confederacy. It might invest the Union war effort with a new and nobler purpose.

September 17, 1862, was a day of high drama both on the battlefield and in Washington. Thus, Ive elected to cut back and forth between the two locales. While my account covers the fighting in full, attending to Antietams legendary (and horrific) sites of conflict, including the Cornfield, Bloody Lane, and Burnside Bridge, the story also circles back to the president.

on slavery out of the war effort.

As for Lee, the contrast with Lincoln is stark. The Virginia-born general and Indiana-bred president make for perfect foils. Nevertheless, standard Antietam books attend to Lee almost exclusively as a military leader. The focus tends to be on Lee as brilliant battlefield tactician (oh, was he ever!), while the thorny issue of Lee-as-slaveholder gets conveniently ignored. Lees views on the so-called peculiar institution as well as his treatment of his own slaves belongs in any modern take on this nineteenth-century event.