Copyright 2018 by John Lingan

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-93253-1

Portions of this book originally appeared in the Morning News,The Baffler, and BuzzFeed.

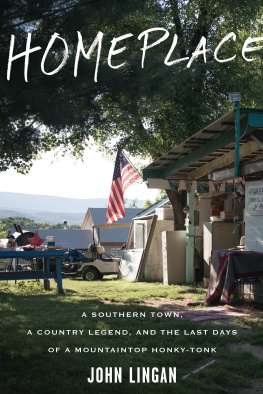

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Cover photograph Matthew Lincoln Yake

Author photograph Pat Jarrett

e ISBN 978-0-544-93083-4

v1.0618

For Justyna

Music seeks to change life;

life goes on;

the music is left behind;

that is what is left to talk about.

Greil Marcus

Preface

In August 1716, lieutenant governor Alexander Spotswood led sixty-three men and seventy-four horses on an exploratory mission across the Rappahannock River valley and into Virginias Blue Ridge Mountains. So far as any of them could tell, they were walking into unpassable darkness: the dense ocean of trees was daily shrouded in mist and clouds. The Knights of the Golden Horseshoe, as Spotswoods band of German, Scots-Irish, and Native American muscle was later known, hacked through the forest until finally they found the Swift Run Gap, a narrow pass in present-day Stanardsville. From the peak of the Blue Ridge, they had view of a North American Avalon, an endless horizon of wide skies and pastoral splendor that looked, more than anything, like the lush, mountainous English Lake District that was soon to inspire the Romantic poets. The unblemished Shenandoah Valley was a setting that might leave a man Alive to all things and forgetting all, as Wordsworth felt about the Lakeland. Spotswood had gone looking for a trade route and ended up in paradise.

From that point on, according to one Indian testimony of the time, the white men came like flocks of birds. Some crossed the mountains and went north on the Valleys Great Wagon Road, where they encountered Pennsylvania Dutch explorers who had come down through the Cumberland Valley. Within years, the Europeans built houses, barns, roads, a route back to the coastal colonies, and infrastructure for grain and livestock farming. In 1738, a little hamlet called Frederick Town was incorporated on a wide, flat expanse up toward the Potomac River, perfectly positioning it as a trading post. The new settlement attracted craftsmen and Quakers, gentry and rabble. By the time its name was changed to Winchester in 1752, the town was a hubthe de facto capitol of what was then still the Wild West.

The border kept moving, of course, but Winchester maintained its odd duality of economic prominence and cultural seclusion. George Washington commanded troops there during the French and Indian War. In the nineteenth century, it was the biggest commercial market in the Shenandoah and the site of multiple pivotal Civil War battles. And starting between the world wars, it became best known as the home base of Harry Flood Byrd, the most influential southern senator for nearly four decades and the leading grower in the world-famous Valley apple industry. Through all this, for more than two centuries, the social order stayed ironclad. The same wealthy families owned everythingjobs, government, and mediaand everyone else just hoped to be employed by them.

By the time I first came to Winchester in early 2013, the apple acreage had been largely replaced by corporate land holdings and housing sprawl. The Washington and Civil War stories had been subsumed into local lore and historical tourism draws. In many ways, twenty-first-century Winchester was just an archetypal early-American town: a cozy historic district circumscribed by highways and big-box shopping, increasingly diverse but still politically conservative and a little dull. The kind of place where people knew their neighbors genealogy and filled prescriptions at a pharmacy whose perfume shelves were misted over with ancient dust. The sole local paper, the Winchester Star, remained independently owned by descendants of Harry Flood Byrd.

I had come to learn about Patsy Cline, who was born in Winchester in 1932 and spent most of her life there, suffering the indignities of wealthy men and women who considered her common. I still dont understand what people think theyll find in an artists homesome experience beyond the art, I suppose, a glimpse of the wide, hidden world that great songs always seem like advertisements forbut when I learned that a legend had grown up less than two hours from my house in the D.C. suburbs, I followed the well-worn path. Thousands of aficionados have gone to Winchester ever since the singer died tragically in 1963, and when you arrive and start asking questions, the Patsy people all tell you: You have to go see Jim McCoy. He was an old man who had known Patsy in his youth, and for years he had owned and operated the Troubadour Bar & Lounge, the only twang-and-sawdust roadhouse left in the Virginias. If you want to understand how this place works, everyone said, you need to head up to Jims compound in the Blue Ridge of West Virginia and see what hes made.

How right they were. First and foremost, this book is about Jim McCoy, a humble Valley lifer who contributed to a momentous, underappreciated era in American music, and a perfect emblem for all the unheralded working people who made that music what it was. From a drafty mountaintop house without electricity, he managed to create a life and a legacy in entertainment, writing and recording dozens of his own songs and many more of other peoples. He made it to Nashvilles inner sanctum and eventually to the Opry stage. His story is not a rags-to-riches saga, but something more complex and bittersweet. In a time of extraordinary change and upheaval, as interstates sprang up and the orchards turned to housing tracts, he embodied an older tradition, and empowered many of his neighbors whose livelihoods had become threatened by all this so-called progress. Ultimately, as I saw up close, he suffered in the manner of those neighbors as well.

Over the course of countless nights at the Troubadour and with the people who live near it, I came to see that the Winchester region, for all its sleepiness, was actually in the final throes of a full-scale transformation that began more than a half-century earlier. Starting in the 1950s, a new business progressive mindset replaced the previous southern focus on agriculture, and Virginia, the upland Shenandoah in particular, went all in. Shenandoah University, a small Methodist school originally located in Dayton, about an hour south, relocated to the east side of town in 1960. In 1965, a length of Interstate 81, which runs from Tennessee to Canada, opened on the citys eastern border. The Apple Blossom Mall arrived in the mid-1980s and chain stores spread around it like a rash. Virginias sole inland port was built just 12 miles south of Winchester in 1989, so shipping traffic, of all things, now accounts for part of the regions economic pull as well. The current Winchester-Frederick County Manufacturing Directory includes more than a hundred companies, most of which have come to the area since the late twentieth century.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Winchester regions expansion rivaled that of any other region in the United States. Inside the Winchester limits alone, the population increased 7.4 percent from 1990 to 2000, and 11 percent from 2000 to 2010. U.S. manufacturing employment decreased throughout the same time, but Winchester-Frederick Countys spiked. The first industrial parks were built in the 1980s, and they expanded to cover a shudderingly vast swath of land above the city limits along the interstate. There is new money here, more than ever before, but the inequality is arguably no better than it was in Harry Flood Byrds time. The region still has manufacturing jobs, but that work is less stable and sufficient than it once was. There is heroin, delivered through all those nearby highways, and widespread health struggles, a result of rising health-care costs. There are immigrants, too, mostly from Mexico and points south, trying and often struggling to find that elusive better life. Turns out that this little town of 25,000 is in fact a brutal microcosm for the entire country, a place where the deepest history and most pressing contemporary concerns are in constant collision.