Published by

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS

P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.scholarlypress.si.edu

2014 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

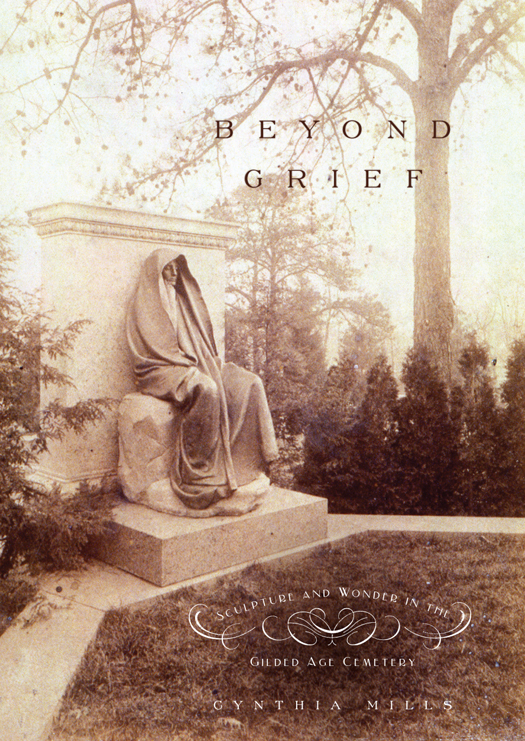

Front cover image: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Adams Memorial, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Photo by George Collins Cox. Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Mills, Cynthia J.

Beyond grief : sculpture and wonder in the Gilded Age cemetery / Cynthia Mills.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-935623-37-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-935623-38-0 (ebook) 1. Sepulchral monumentsUnited StatesThemes, motives. 2. Sepulchral monumentsPsychological aspects. 3. Art and societyUnited StatesHistory19th century. 4. Art and societyUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

NB1803.U6M55 2014

731.76dc23

2014004894

ISBN-13 (print): 978-1-935623-37-3

ISBN-13 (ebook): 978-1-935623-38-0

v3.1

C O N T E N T S

I N T R O D U C T I O N

On a chilly Sunday morning in December 1885, Henry Brooks Adams pulled on his winter coat and stepped out onto the front portico of his home on Lafayette Square across from the White House. Perhaps he was feeling some discomfort, for by all accounts Adams, the well-known descendant of two presidents, was on his way to visit a dentist. Before he had ventured far on the tree-lined street, however, he encountered an acquaintance arriving to see his wife. Adams turned back, reentering the three-story stone house on H Street to call her. Met by silence, he climbed the stairs to an upper room. There he found forty-two-year-old Marian Hooper Adams slumped unconscious on a rug in front of a fireplace. The celebrated Washington hostess, a talented amateur photographer, had poisoned herself by drinking potassium cyanide, a toxic chemical used in developing film. A doctor, hastily summoned, could do nothing to revive her. Her body, still warm to Henrys first anxious touch, grew cold and rigidan insensate corpse replacing the vibrant woman he had loved. Thus began for a shaken Henry Adams the unrelenting cycle of grief, remorse, questioning, self-doubt, anger, and psychic exhaustion that haunts the survivors of suicides.

Adams equated his experience with Helldescribing himself as unsteady, not calm, and not myself in days to come. Life could have no other experience so crushing, he wrote one friend. This wretched bundle of nerves, which we call mind, gives me no let up, he told another. All my energy is now turned to the task of endurance, he confided in a letter to Oliver Wendell Holmes two weeks later.

Adamss search for release from ceaseless waves of dark and troubling thoughts became a consuming obsession but also a generative force with an impact beyond his own great loss. For this personal tragedy led him on a quest for a consoling, cathartic beauty that he hoped would ease his mental torment and restructure others perceptions. The result, more than five years later, was the Adams Memorial, designed by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in a setting by Beaux-Arts architect Stanford White.

One of the most extraordinary American funerary monuments of the nineteenth century, the bronze figure sits meditating on a granite seat in a quiet Washington, D.C., cemetery. Called a modern sphinx for its quality of shrouded mystery, it became the most widely known and influential of a number of figurative grave memorialsincluding the moving Milmore monument in Bostonthat were completed by some of the nations finest artists in the 1890s (Plates 1, 2).

These memorials were sometimes created in highly personal relationships between survivor and sculptor. Artists like Frank Duveneck and the elderly William Wetmore Story made memorials to their wives after suffering loss (Plates 3, 4). Models, photographs, or replicas of the new high-style sculptural monuments were later displayed in arts exhibitions and in such elite venues as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as well as in the precincts of death, inspiring other patrons, artists, and artisans to imitate or attempt to rival these achievements. The new memorials, frequently undertaken in partnership with architects and landscapers, helped to change the face of the American cemetery, already in the process of transformation in the decades following the Civil War. Among patrons and fine artists a great interest was developing in beautifying the cemetery following the deaths of 620,000 in the war. The land, pierced by shovels and turned repeatedly to make way for the casualties of military battles, was being heaved and hewn into the foundation for a new aesthetic, a more unified and centrally managed landscape of sensations. New attitudes toward mortality and mourning were emerging alongside a growing industry manned by deathways professionals ranging from undertakers to cemetery managers.

The artists who created this generation of private memorials avoided older sentimentalism and often modified or cast aside standard elements of religious symbolism and the reassuring inscriptions about the afterlife that had characterized many earlier monuments. They turned their sculptures into statements about modern life and death by seeking to meld grief and wonder in a nonverbal form. Death, their cemetery sculptures still tell us today, remains an event beyond human comprehension, even for faithful Christians. Survivors must learn to value their inability to explain it and turn its mournful riddle into a positive power that stimulates the imagination and the heart. They must come to revere its sheer mystery, cloaked in an aura of beauty in the cemetery, where an awe of nature and art can spur meditation on universal questions.

The monuments were intended to be vessels for catharsis, meant to console, but they also served other purposes. They could manipulate and mask, becoming vehicles for instilling an emotional and social legacy, or for denial of such negative emotions as guilt and excessive grief by individuals who above all feared loss of control over their feelings and reputationsturn-of-the-century Americans who lived with a dread of ridicule and shame.

Elite patrons and artists hoped that reverent and respectful spectators would find in their sculptures suggestions of dignity, nobility, serenity, order, and refinementforms of beauty and peaceful stability in a situation that by its very nature was full of trauma and uncertainty. The artworks often denied or veiled the ugliness of death and the fragility or baseness of human motives. They participated in a struggle for grace amid wrenching societal change in the postwar era and, eventually, in a post-Darwinian age, when elites such as Bostons Brahmin class sensed a fracturing of lifes wholeness. Placed in lovely outdoor garden settings, the

Evolving in dialogue with older, more highly ornamented forms of sepulchral sculpture and with the rise of American art museums, these exceptional 1890s cemetery monuments were reinterpreted in the early twentieth century. A generation of Americans discovered them through personal pilgrimage or, more often, through widely distributed reproductions and illustrated popular magazines and newspapers. But these diverse outsider audiences viewed the monuments through the lens of an increasingly urbanized consumer society now influenced by mass media, advertising, varying forms of public spectacle, specialization and professionalization of labor, and new modes of mass manufacture and replication. With the rise of motion picture technology, the multiple funeral processions for assassinated President McKinley were captured by Thomas Edisons cameras in 1901, for example, after a little-known commercial sculptor named Eduard Pausch had carefully measured the presidents features and preserved them in the form of a plaster death mask that could be the basis for memorial statues.