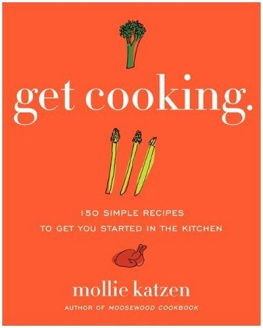

Minding the Manor

Minding the Manor

The Memoir of a 1930s English Kitchen Maid

Mollie Moran

I dedicate this book to my late mother, Mabel, and all my family.

Copyright 2014 by Mollie Moran

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

First published in the UK in 2013 as Aprons and Silver Spoons by Penguin Books.

First published in the USA in 2014 by Lyons Press, an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Lauren Brancato

Layout artist: Melissa Evarts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0408-9

Contents

An Idyllic Childhood

Sweet was the walk along the narrow lane

At noon, the bank and hedge-rows all the way

Shagged with wild pale green tufts of fragrant hay,

Caught by the hawthorns from the loaded wain,

Which Age with many a slow stoop strove to gain;

And childhood, seeming still most busy, took

His little rake; with cunning side-long look,

Sauntering to pluck the strawberries wild, unseen.

William Wordsworth

Inching higher and higher, I used every fibre of my being to pull my body further up the tree trunk. Just one more foot and Id be there. The prize was in sight and it was worth its weight in gold.

Come on, Mollie Browne, you can do it.

With a superhuman show of strength and a grunt I swung my leg over the branch and sat gasping for breath.

Id climbed to the very top of the tallest oak tree in the village.

It started as a tingle in my chest and soon spread to the tips of my fingers. Joy flooded my body. Id done it. Id only gone and done it. No one had climbed this tree, not even the bravest lads in our village.

Sissies, I chuckled to myself. I may only have been a ten-year-old girl, but I was more of a man than any of them.

My mother Mabels warning, issued just before I left the house that morning, rang in my ears: Come straight home from school and dont be scuffing your shoes or ripping your dress climbing trees on the way. And dont you be nicking all them eggs out the nests again. I mean it, Mollie Browne, any more trouble and Ill swing for you, I will.

I looked down at my ripped cotton dress. Oops, too late. And by the way the sun was dipping down below the spire of the church I could tell dusk was gathering.

I hesitated. What were rules for if they werent to be broken?

The thought of the telling-off I was going to get melted away when I realized I could see for miles around the tranquil landscape. What a thrill. It was like discovering a secret magic world; just me and the birds in the twilight. Fields dotted with ancient flint churches stretched out as far as the eye could see. In the distance I could make out the town of Downham Market and just beyond that the sun glittered off the River Great Ouse.

The year was 1926. Coal miners were striking, John Logie Baird had just given the first public demonstration of the television, and Gertrude Ederle had become the first woman to swim the Channel. These were exciting times. London was in the grip of the Roaring Twenties. Bright young socialites wore their hair in bobs, their skirts short, and were dancing up a storm in jazz clubs. Their louche and provocative behaviour was blazing a trail across the front pages.

Here in gentle Norfolk it was a different story.

A tractor rumbled in the middle distance, ploughing straight lines through the soil. Fields of wheat and barley rustled gently in the breeze. All was still, quiet, and timeless.

This was my world. Mollie Brownes world. One giant playground full of adventures just waiting to be had. But even as I surveyed the peaceful landscape I felt the strangest sensation grip my heart. My destiny didnt lie here in the sleepy villages, forced into a dull apprenticeship before being married off to the local farmhand. No, thank you. There had to be more to life. I wasnt sure what yet butsure as eggs is eggsI would find a way to make it happen.

At the thought of eggs, I suddenly remembered the reason why I was up this big old tree in the first place. Wiping the sweat off my brow, I forced myself not to look down and edged along the gnarled branch to claim my prize. Two perfect brown speckled eggs were sitting in the nest within touching distance, still warm from when the crow had hatched them.

I wasnt daft. Id never pocket a wrens or robins egg. Everyone knew bad luck would come your way if you nicked those and your hands would fall off. Happen there be no harm in a crows egg, though.

Just then a sharp whistle sounded from below.

My partners in crime!

I could just make out the faces of Jack and Bernard.

Its the bobby, Jack hissed. Get down afore he sees ya.

Oh heck. There was no time to pocket either of the shiny brown eggs. Instead I shimmied down that tree faster than a rat down a drainpipe. With a loud thud I landed slap bang in front of the black laced-up leather boots of one P. C. Risebrough. My nemesis. I swear that man spent his whole time roaming the countryside looking for me. He always seemed to know just where to find me!

Mollie Browne again, he said in his thick Norfolk accent. Slowly he shook his head. If theres trouble to be found its always you in the thick of it, ainch ya? When will yer learn?

Last summer hed caught me with handfuls of stolen strawberries. Thered not been a soul about, until the sight of his tall hat bobbed past over the top of the hedge. Hed clouted me so hard round the lugholes that my ears had been ringing for weeks.

I shook my head as I saw Jack and Bernard turn on their heels and leg it. I was just mucking about, I said, shaking my red curls vigorously. Avin a gorp from the tree.

He peered down at me, narrowed his eyes, and slowly and deliberately peeled off his gloves. Thas a lotta ol squit, he said. Stealing eggs you was. I oughta box your chops.

Two minutes later, and with my ears ringing from another clip, I ran for home.

Any more trouble and Ill be letting your father know, P. C. Risebrough shouted after me. Now git orf wiv yer.

My heart sank as I raced off down the fields. Not again. He was forever catching me doing things I shouldnt and my father was forever telling me off. I didnt want to trouble Father, not in his condition, but trouble just seemed to seek me out.

I ran so quickly across the fields and lanes that the bushes became a blur of green. I could run in them days. I was so strong and fast it wasnt true. So fast that at times I felt I could have flown clean over the hedgerows like a swallow, swooping and soaring.

At the end of the lane that led to our tumbledown cottage I paused and looked back over the fields. Dusk was sneaking gently over the village and soon the fields would be cloaked in a velvety darkness. Smoke curled gently from the chimney pots and suddenly my tummy rumbled. I thought of bread and dripping by the fire, or if I was lucky we might have a bit of meat in a steak and kidney pudding. Machine-gunning my way up the lane that led to our smallholding, I startled a blackbird that flew chattering from the hedgerow. My heart soared as I ducked through the hedge and crept down the back garden. It was Monday, washing day. Mother would be too busy to notice I was late for tea.