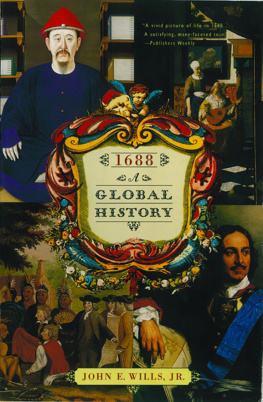

1688

A Global History

John E. Wills, Jr.

W.W. Norton & Company New York London

ALSO BY JOHN E. WILLS, JR.

Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History

Embassies and Illusions: Dutch and Portuguese

Envoys to Kang-hsi, 16661687

(coedited with Jonathan D. Spence)

From Ming to Ching: Conquest, Region, and

Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China

Pepper, Guns, and Parleys: The Dutch East India

Company and China, 16621681

I stumbled across some of these stories in the course of my conventional research on European relations with China. At first I thought I would collect material on 1687 or 1689, to avoid the complexities of the Glorious Revolution, but Constantine Phaulkon in Siam and Shi Langs envoys to Madras made 1688 unavoidable. There has been no end of serendipities. I had never heard of the Coronelli globes before I saw one by chance in a museum in Brussels. In July 1995 I followed a historical monument marker to the Slovenian country house of Janez Valvasor, of whom I had never heard. In 1997 I was able to visit Dampiers landfall on the coast of Australia and the fort on Ambon where Rumphius fell under the spell of tropical plant and animal life. In February 1999 I traced Phaulkons last day in Lopburi. Serendipity, surprise, and letting one thing lead you to another are not attitudes often associated with the methodical world of the professional historian. Not many historians will want to give them as free rein as I have in this book, but many will acknowledge that they are part of what makes their hard work fun. This book has been fun to do. And what a privilege it has been to spend time with William Penn, with Bash, with William Dampier!

Serendipity produces an amazing and scattered array of debts of gratitude. Many of my colleagues in the Department of History at the University of Southern California have at one time or another responded to my requests for guidance or bibliography for this book. My debts are largest to Ayse and Hari Rorlich, for indispensable help with Russian and Middle Eastern materials. Others at USC include Marjorie Becker, Gerald Bender, Marguerite Bistis, Michael A. Burnstine, Thomas Cox, Charlotte Furth, Paul Knoll, Philippa Levine, Edwin McCann, Peter Nosco, Edwin Perkins, Carole Shammas, Lisa Silverman, Joseph Styles, and Shaoyi Sun. Connie Wills, Diane Wills, and Jeff Wills were a most helpful focus group in final editing agonies. Widening circles of helpful colleagues, from across the street to around the world, include Kim Akerman, E. M. Beekman, Leonard Bluss, David Ellenson, Lory Friedfertig, Aubrey Graatorex, Richard Hovanissian, Allen F. Isaacman, David Northrup, Demy Ohoilulin, Dhirivat and Pajrapongs na Pombejra, Branko Reisp, and Shalom Sabar. The libraries of USC and their Interlibrary Loan staff have been basic resources. I also have benefited from the riches of the libraries of the University of California at Los Angeles and the Huntington Library. The various funding agencies that made possible my research stays in Beijing and in The Hague and my brief visits to various parts of Europe and ports of maritime Asia, and the local authorities and archivists who facilitated my work, are thanked in detail in my monographs. I owe a special debt to Steven Forman of W. W. Norton & Company, who saw the merit of this eccentric project, waited with amazing patience while it moved forward and backward in my queue of things to be done, and provided a kind of engagement with the intellectual substance of my work I had never encountered in "academic" publishing. Geoffrey Parkers supportive comments and astute criticisms of an early draft were very important.

My wife and our family have been bemused, patient, impatient, as most families are with someone caught in an apparently interminable labor of love. Our daughter, Lucinda, and her husband, Muhammad al-Muwadda, advised me on matters Islamic and gave me a T-shirt inscribed 1688the best year of my life that wore out before the book got done. One of the delightful fringe benefits of over forty years with Carolin Connell Wills has been that with her I acquired an uncle, Robert H. Irrmann, for many years professor of history at Beloit College. A scholar of England in the 1680s and a much-admired teacher and teller of stories, he gave much astute advice and always was ready for another 1688 story. This book is dedicated to his memory in affection and gratitude. I am especially pleased that in his last years he knew of the progress of this work and had in his hands a full typescript of it.

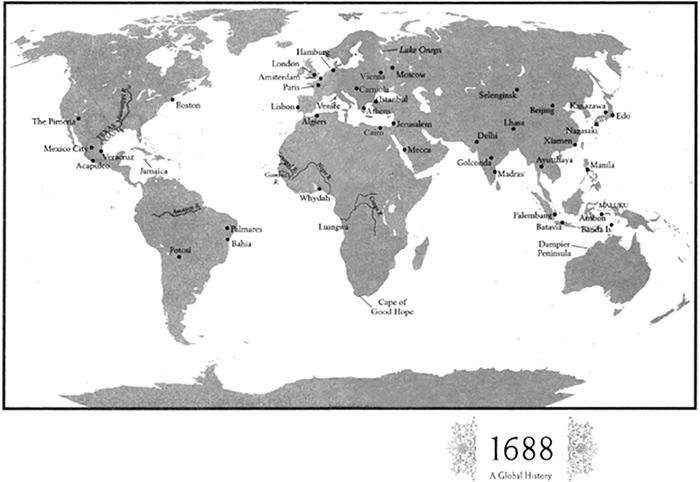

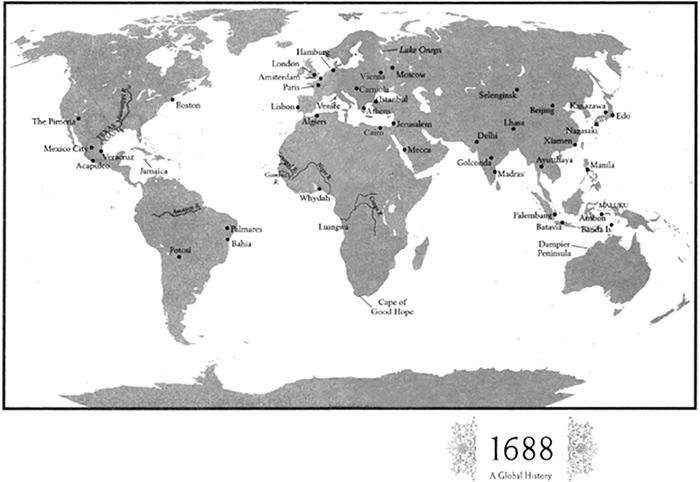

A s the earth turns, the light of the sun moves from the gray and pale blue of the Pacific onto the forests and fields of the coasts of Japan and Luzon. In the seething energy and hard-won order of the streets of Edo, the great capital city of Japans hereditary military dictators, the heavy wooden gates of residential quarters are swung open. Chanting and gongs are heard faintly from Buddhist temples. Shopkeepers open their shutters and arrange neat displays of fine wares from all over the country. Depleted roisterers slump away from the pleasure quarters and dodge into alleys as samurai horsemen ride past, their swords clattering.

In Manila, on Luzon, the sound of bells echoes from the great churches in the center of the city, south of the swamps along the Pasig River, and from the more modest ones in the Chinese Christian suburbs north of the river. Junks have begun to arrive from the ports of China. There is talk that there may not be as many as last year because of the growing tension between the Chinese and the rest of the population. How will the faraway authorities in Madrid and Mexico City reply to the litany of Chinese violence and treachery in the Manila authorities letters? Might there even be another descent of Chinese pirates on this farthest outpost of the Spanish Empire of Catholicism and silver?

Far to the south, on a rocky piece of the northwest coast of Australia, William Dampier, gifted naturalist and barber-surgeon to a gang of buccaneers, is up and about, timing carefully the shifts of the daunting tide races, keeping an eye on the native people watching warily from a hilltop. He thinks them pitifully primitive, no danger, but certainly material for a great story if he lives to get home. At high tide the midges swarm and get into his eyes.

As the light reaches the great red walls and yellow tile roofs of the imperial palaces of Beijing, a singular procession heads south through the enormous gates. The banners and guardsmen are present in full array. The emperor himself is walking. He is on his way to the open Altar of Heaven, where he will face the cold winter sky and implore High Heaven to take years from his life and bestow them instead on his dying grandmother.

And as the light comes to the Ox Street Mosque on the west side of Beijing and to the airy, tropical mosques of such southern islands as Mindanao and Ambon, the muezzins call the faithful to morning prayer. Several hours later the muezzins calls echo across Hyderabad in southern India and the splendid camp on its outskirts of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and his huge army. Some of the emperors generals are Hindu, but he and most of his generals are Muslims, now bowing toward Mecca in their morning prayers before they turn to the exacting tasks of preparing their forces for another campaign. And now the muezzins calls are everywhere in every dawn, in Isfahan and Samarkand far to the north, in Mecca, Cairo, Istanbul, in embattled Belgrade, Algiers, Timbuktu.

Next page