CONTENTS

BY M ICHAEL P ORTILLO

FOREWORD

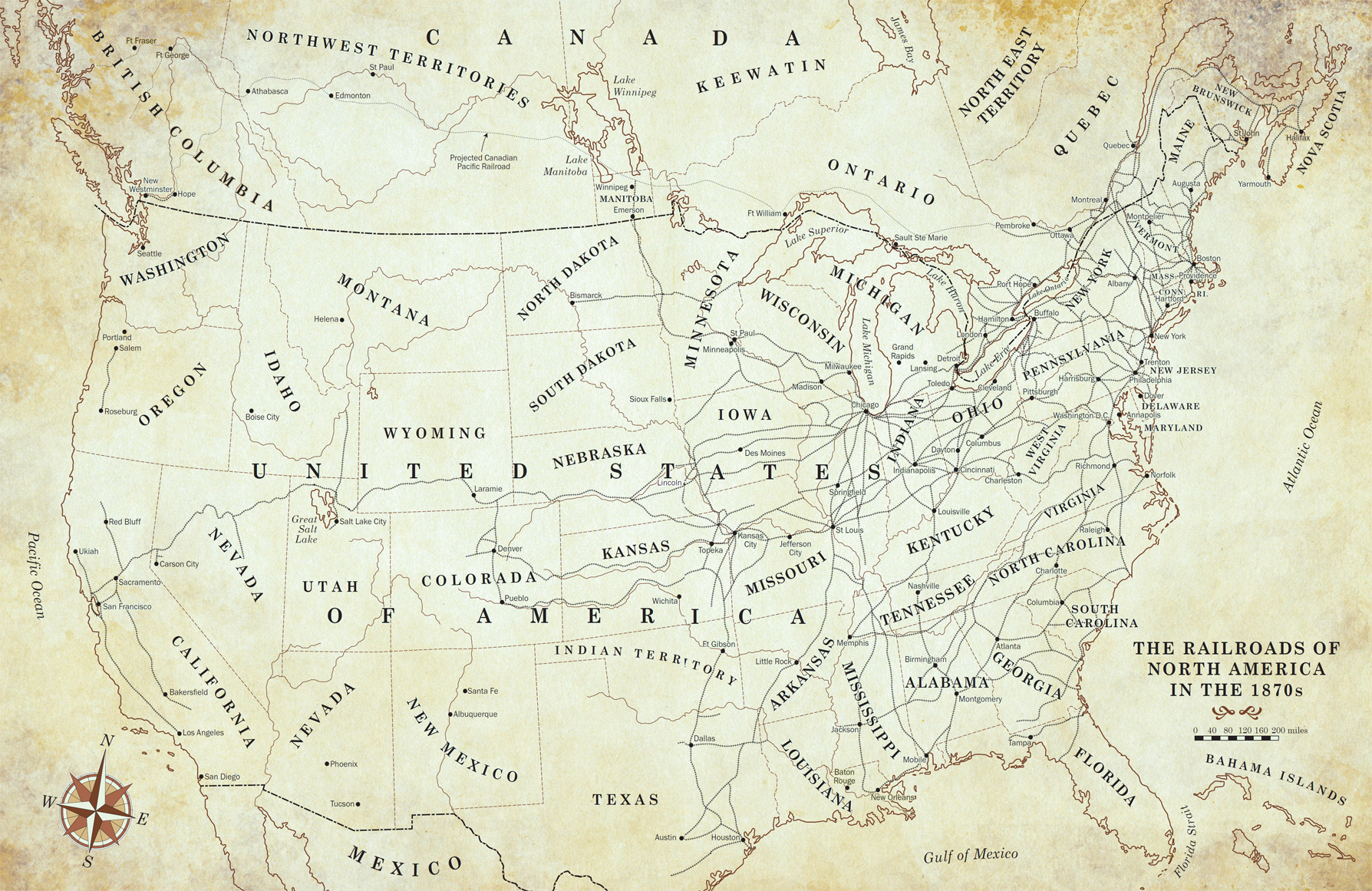

T hroughout the years of making rail journeys for BBC television, first in the United Kingdom and then on the continent of Europe, I had dreamed of carrying the programmes concept to the United States. Although Britain was marginally ahead of the US with its first inter-city passenger railway, the Americans soon had a vastly greater network. Some Americans had worried that as their country pushed out rapidly to the west it would break up, becoming merely a collection of nations like Europe. The tracks and the locomotives may have arrived just in time to knit the expanding nation together.

Alas, there was no Bradshaws handbook to steer me across the US, but a father and son called Appleton produced a General Guide to the United States and Canada , promising to illuminate all that is novel, picturesque, beautiful, memorable, striking or curious; and I ventured forth with volumes published around 1879. Like Bradshaws, they guided me to journey by train, opening up for me not just the continent but also the American state of mind little more than a decade after the end of the devastating Civil War.

As I soon discovered on my American rail journeys, it would be a mistake to forget the waterways and canals that preceded the tracks. The building of a canal in 1825 between Lake Erie and the Hudson River meant that grain from the Midwest from as far afield as Minnesota could pass via grain silos in Buffalo, New York down to New York City, and then across the Atlantic to feed Europe. The trade sealed the citys fortune, making it Americas principal port.

The advent of the railroads speeded up everything, and the tracks were less susceptible than the canals to freezing. In a gilded age, they made great fortunes for tycoons, and in the second half of the nineteenth century they helped to unleash a revolution in heavy industries.

In the era of Rockefeller, Carnegie and Vanderbilt, the industrial success of the US and its expansion westward sucked in millions of European immigrants fleeing persecution or poverty, huddled masses yearning to breathe free, many passing through New Yorks Ellis Island.

As I explored New York State, I saw the Long Island mansions of the tycoons and the Manhattan tenements of the immigrants; and then I enjoyed the serene beauty of the mighty Hudson from my train seat, as it hugged the river bank mile after mile, before delivering me to witness the awe-inspiring power of Niagara Falls.

My rail journey south from Philadelphia confronted me with the political rather than the industrial history of the Americans. In 1607, three ships landed English colonists in continental America, where they constructed James Fort (near present-day Jamestown) in Virginia, the colony named after Queen Elizabeth. They soon came close to starvation and may have been saved by Native Americans (including Pocahontas) who thought it in their best interests to help the Europeans to survive.

Virginia became the pre-eminent colony by wealth and population. The revolution against British rule, preceded by skirmishing in Massachusetts, might not have occurred had mighty Virginia not voted for rebellion. Certainly, it was a Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, who drafted the Declaration of Independence, and another, George Washington, who emerged as the hero of the war against the Crown, and the unanimous choice to be first president of the United States.

When I visited the Liberty Bell, cast in Whitechapel in London and already hanging in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia when the Declaration was proclaimed, I was deeply impressed by the noble ambitions of the revolutionaries. All men are created equal and entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

However, back in 1619, Virginia had imported, for the first time, slaves from Africa. The slave population had then grown enormously. The agricultural economy, at least of the south, was thought to depend on slavery. The Founding Fathers perceived the contradiction that the United States was the land of the free and the home of the slave, but no political solution could be found at that time.

President Abraham Lincoln got off the train at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on 18 November 1863 to attend the dedication of the cemetery where lay buried Union soldiers killed in the battle of the previous July. The norths aim (in what turned out to be the first American railroad war) had been to preserve the Union against secession by the Confederate states, rather than to abolish slavery; but in his Gettysburg address Lincoln, in a few brief remarks, recalled the words of the Declaration and committed the victors to a rebirth of freedom. Emancipation was to follow.

As always, my travels through history were punctuated by escapades. They helped me to understand the American cultures that have emerged from the countrys diverse origins. At Nathans on Coney Island, New York, there is a competition for how many hot dogs a person can consume in ten minutes! It is not for the faint-hearted. While on Long Island, I relived the era of F. Scott Fitzgeralds The Great Gatsby with a painfully incompetent attempt to dance the Charleston. In Philadelphia, I put on the shoulder pads and helmet of an American football player. In Virginia, in the elegant setting of the Richmond Womans [sic] Club, I joined a cotillion, where the more refined sort of teenager (boys in bow ties, girls in pretty dresses) learns etiquette and the cha-cha-cha. In nearby Petersburg I was stirred by the rhythm and beat of the gospel choir of the First Baptist Church. Ploughing a furrow or two behind yoked oxen in Williamsburg, Virginia helped me to understand how proud colonials became independence-minded, as their own representative political institutions matured.

After the Civil War, new railroads helped to tie together the disunited states. But when I alighted from the train in Baltimore and then Washington, D.C., I met African Americans who believe that the progress towards equality, begun with the postwar emancipation of the slaves, still has far to go.

That does not make me cynical. To this day, the founding ideals of liberty and equality resonate with Americans. They provide them with clarity, unity and a sense of purpose, great strengths in a nation that is still filled with hope for its future.

Michael Portillo