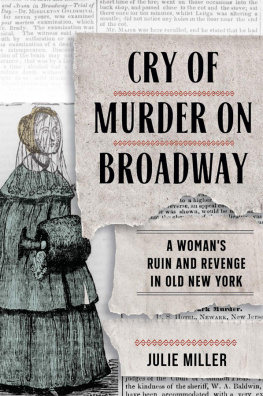

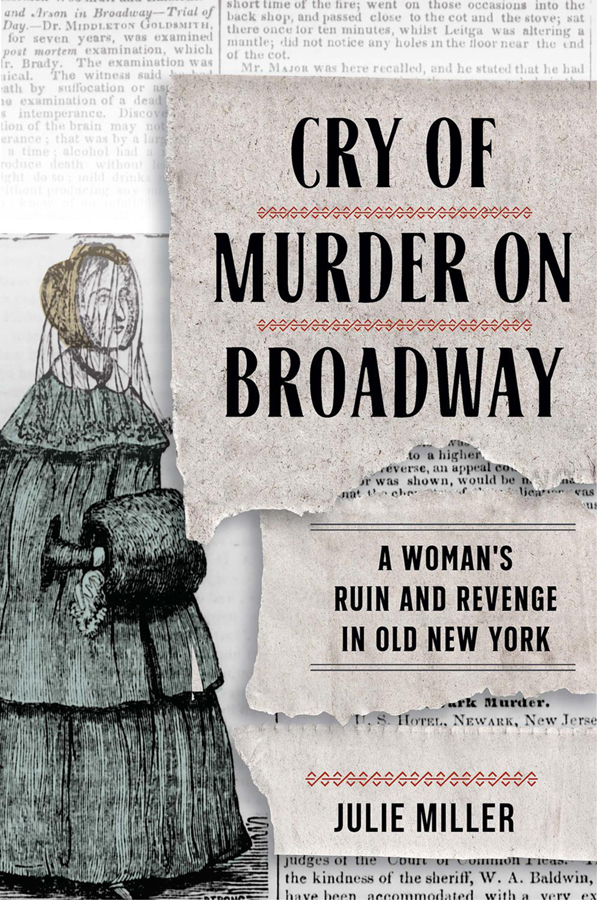

Julie Miller - Cry of Murder on Broadway

Here you can read online Julie Miller - Cry of Murder on Broadway full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Cry of Murder on Broadway

- Author:

- Publisher:Cornell University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cry of Murder on Broadway: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Cry of Murder on Broadway" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Cry of Murder on Broadway — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Cry of Murder on Broadway" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In memory of Minnie Singer Miller and Mollie Meyerowitz Silver, my grandmothers, who began their American lives as immigrant girls in New York

The wonder being, all the while, as we look at the world, how absolutely, how inordinately, the Isabel Archers, and even much smaller female fry, insist on mattering.

Henry James, Portrait of a Lady , preface to the New York edition , 1908

On November 1, 1843, a young woman dressed in black and carrying a large fur muff followed a man up the steps of the magnificent new Astor House Hotel on Broadway in New York. After what appeared to witnesses to be a brief conversation, she pulled out a folding knifeand stabbed him.

The reporters who later saw her recognized the horror of what she had done, but they were also quick to conclude that because she was the heroine of a story, she must be beautiful. Over the next two days the New York Express reported that the wretched female who thus sought to imbrue her hands in blood is an elegant appearing woman, tall and of beautiful figure and form, wearing a splendid black dress. When she appeared in court the following January, James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, made a deeper observation, noting that she was a girl evidently of no ordinary character. Her hair and complexion are fair, but her eyebrows and eyes are very dark, giving an expression of sternness to a face which otherwise would justly be considered strikingly handsome. A Herald reporter saw the expression of character that his editor described, but described her physical appearance somewhat differently. According to him, Norman had very dark brown hair, expansive forehead, heavy eye brows and lashes, with a melancholy but very determined expression of countenance. In the woodcut portrait the Herald published during Normans trial, her hands, face, and body are so obscured by her tiered dress, large fur muff, hat, and veil that it is almost impossible to tell what she looked like, allowing the papers readers to imagine whatever they liked best or expected to find.

The woman was twenty-five-year-old New Jerseyborn Amelia Norman, a servant, seamstress, and sometime prostitute. The man she tried and failed to kill was thirty-one-year-old Henry Ballard, a prosperous merchant originally from Boston. Norman had become Ballards mistress in the spring of 1841 during the depression that followed the economic collapse known as the Panic of 1837. After little over a year, during which Ballard moved her from one boardinghouse to another, he left the country, abandoning her and their child. When he returned, Norman pleaded with him to help support them, but Ballard refused. Instead he told her to go and get her living as other prostitutes did. It was this rebuff that evidently created the state of mind that pushed Norman to pursue Ballard up the stone steps of the Astor House on the night of November 1, 1843, and put a knife in him. Or, as Bennett put it, the vengeance of a woman upon her despoiler cannot be checked, when jealousy and desertion goad her to its accomplishment.

The trial of Amelia Norman attracted the excited attention of the penny press, particularly Bennetts Herald, which thrived on sensation. Newspaper editors around the country, recognizing the interest the story was generating, republished it for the benefit of their own readers. People daily filled all three hundred seats in the courtroom, crowding the room to excess, while as many as a thousand more who couldnt get in packed the lobby and spilled out the door, down the steps, and into the street. Years after the trial an observer remembered that so great was the public interest in her that on the night the verdict was rendered, the courthouse was besieged by thousands of our citizens, and when the result was announced, the welkin rang with the plaudits of an excited populace!

What was it about this would-be murderess that attracted the attention not only of the press and the public, but also of a coterie of influential supporters? These supporters included the members of the American Female Moral Reform Society, who had been working since the 1830s to criminalize seduction, the concept then current in common law that allowed a womans father or master to sue her seducer on the basis of loss of services to himself. After her trial, and probably partly as a result of it, one of Normans lawyers, David Graham Jr., attacked the seduction tort from a different angle, seeking to make it possible for a woman to sue on her own behalf. In the age of the movements for abolition and womens rights, reformers, including legal reformers like Graham, were seeking to jettison the idea that anyone could own the labor of another.

Two very different voices that spoke out in support of Norman belonged to Mike Walsh and George Wilkes, who were in jail when she was and met her there. Walsh, then around twenty-eight years old, was a leader of a radical splinter of New Yorks Democratic Party and the editor of a weekly labor paper, the Subterranean, in which he published two editorials on Normans plight. He was in jail after convictions for libel, and assault and battery. His lawyer was the same David Graham who represented Norman. His friend Wilkes, twenty-seven, was a journalist who had coedited the Sunday Flash, one of the first examples in New York of the flash, or sporting press directed at men. In 1843 Wilkes was in jail for violating the terms of the suspended sentence he had received after being convicted for libel and publishing an obscene paper. While in jail Wilkes wrote a prison memoir, Mysteries of the Tombs: A Journal of Thirty Days Imprisonment in the New York City Prison for Libel, in which he recorded his observations of Norman and his feelings about her predicament. Like Walsh, Wilkes was a champion of the small artisans and workingmen who were struggling to maintain their livelihoods and their identities as men in the industrializing economy. Even though the focus of Walsh and Wilkes was chiefly on the difficulties of men like themselves, and even though they narrowly equated manhood with selfhood, both saw enough of their own plight in Norman to sympathize with her, and did so in their writings.

Of all Normans supporters the closest and most steadfast was the abolitionist and popular author Lydia Maria Child. Child helped find Norman a lawyer, accompanied her in the courtroom, took her home when the trial was over, and tried to help her get back on her feet afterward. Child wove elements of Normans story into her fiction, and she devoted a newspaper column, one in a series titled Letters from New-York, to her. Childs writings about Norman were an avenue for her to develop her position on the cause of womens rights, just then starting to coalesce into a movement. They were also an outlet for her anger at what she called the false structure of society that allowed men to dominate women. In her Letter from New-York No. V, published in the Boston Courier immediately after Normans trial, Child erupted so angrily, and veered so close to condoning Normans violence, that fearing for her literary reputation, she excised six particularly heated paragraphs when the column was reprinted two weeks later in the National Anti-Slavery Standard.

What these supporters had in common, disparate as they were, was that they all read into Normans predicament a parable ready-made for their own use. Storytelling is central to understanding what made Norman matter to so many people. Her crime and trial unfolded at a period of heightened interest in narrative, whether written or spoken. In the 1830s and 1840s in the United States, crowds eagerly listened for hours to political speeches, abolitionist lectures, and revivalist sermons. The mystery novel and investigative journalism are both products of these decades. Rising literacy, mechanization of the processes of papermaking and printing, and spreading democracy all meant that more people read novels and newspapers.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Cry of Murder on Broadway»

Look at similar books to Cry of Murder on Broadway. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Cry of Murder on Broadway and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.