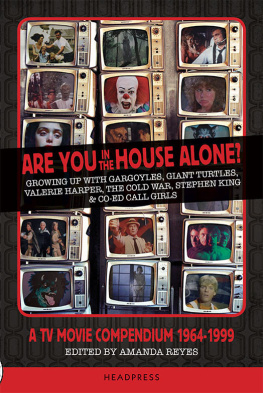

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to David Kerekes and Headpress for giving me an opportunity to put together the kind of book I have always wanted to read. David is a great cheerleader in all the best ways, offering guidance and giving me space to offer suggestions. Honestly, my appreciation goes beyond words. So I will just say thank you.

I am also extremely grateful to each and every contributor of this book. Thank you for all of your hard work and patience.

I should add that I wouldnt be here writing an acknowledgment page for a finished manuscript on television films if it werent for the constant support of my husband, David Cohen. Hes my best friend, greatest companion and champion. His willingness to sit through This House Possessed each and every time I want to watch it proves his dedication to the cause. Thank you. And I love you.

And a special shout out to the late TV movie historian, Alvin H. Marill, whose Movies Made for Television is essentially my Bible. His book laid the groundwork for this journey, and for that I am forever grateful. Rest in peace, sir.

Finally, Id like to thank all of the people who made and still make television films. You have constantly provided me a place of comfort, warmth and joy. Thank you.

Amanda Reyes

FOREWORD

BY JEFF BURR

The network TV movie of the 1960s and seventies is a strange beast, caught between the two poles of Cinema and the invasive, pervasive electronic box that Hollywood initially feared but grew to love. Framed at the Academy ratio of 1.33, which fit perfectly in the pre-HD square Magnavoxes, Motorolas and RCAs, critics likened the TV movie as the next generation B film. And there is some truth to that, as most of the TV movies trafficked in genre subjects and featured familiar actors. But the TV movies had more promotion and an individual identity. Creating movies, real movies, for a new medium with its own unique pluses and minuses involved some artistic pioneering.

The filmmakers who worked on these movies rarely got any real recognition or critical ink, but many of the films got European theatrical releases and played in syndication for years. Directors like Paul Wendkos, Lamont Johnson, Joseph Sargent, William Graham, William Hale and John Moxey worked under incredibly difficult conditions, shooting these movies in anywhere from twelve to eighteen days, and often with incredibly shortened postproduction schedules. In a very real sense, the networks didnt need it great, they needed it Tuesday.

As a kid growing up in a small town in Georgia in the late 1960s through the seventies, entertainment options were limited at best. Being a precocious cinephile, a weekly ritual for me was looking at the TV Guide for the week and seeing what new movies were going to be showing, carefully noting the day and time. A campaign of anticipation then followed, hyping the movie to reserve that timeslot in a one-TV house. More often than not, my mom and dad would be caught up in my enthusiasm ( ANDY GRIFFITH AND CAPTAIN KIRK ON MOTORCYCLES YOU GUYS!! WHAT COULD BE COOLER??? ), and we would be rewarded by seeing Pray for the Wildcats, A Cold Nights Death, Birds of Prey or Brians Song.

The elementary school version of the water cooler conversation was at the monkey bars on the playground. It was there where you learned what you missed, or could tell what you saw. Did you see that movie last night? Andy Griffith played this asshole and he got killed riding off a cliff!! You could rate how the movie entered the zeitgeist by the amount of kids who chimed in and the intensity of the discussion.

And in those days, watching these made for television movies, you knew when they were really special. Some of them just stood out, by way of craft, story and acting. Duel is probably the best example of that. I saw it on the premiere night, and my whole family was riveted. No one walked out of the room, not even during the commercials. I dont know how Spielberg did it, and he says he doesnt either. But probably the biggest single reaction I can remember at my house was for Born Innocent. My dad, my brother and I were watching it, and the infamous (and later cut) scene with Johnny played out. Dead silence, then my dad turned to us both and said, I cannot believe what I just saw.

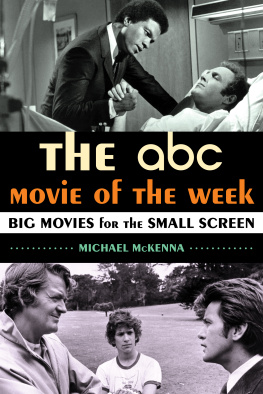

It is instant nostalgia for me and for many people when you see Doug Trumballs slit-scan intro, hear Burt Bacharachs instrumental Nikki and see the bold titles ABC Movie of the Week. It brings back more than just the movies it brings back a time, a place and a moment when your television set turned into a bona fide movie theater and anything was possible. This book will go a long way to rectify the lack of recognition of about thirty years of American cinema that happened to unspool over the airwaves, but totally worthy of a much bigger screen.

FROM CLASSY TO TRASHY: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE MADE FOR TELEVISION MOVIE

BY AMANDA REYES

The seventies are considered the heyday of the made for television movie, and serve as an important benchmark in the landscape of our society. Although the first official telefilm, See How They Run premiered all the way back in 1964, this new version of the feature film didnt really come into its own until a few years later. While TV movies appear in different shapes and genres, the medium, even in its most generic form, was a hit, and thousands of films were released on network television over the next few decades.

It is important to remember that in the earliest days of the television movie, there were only three major networks (four if you count PBS), and a lot of eyes were glued to the boob tube nightly. Network executives devised the TVM (TV movie) as an event, which is not an overexaggeration. Designed to air once or twice, or, if you were lucky, maybe a few more times in syndication, this was the world before time shifting devices like the VCR, or DV-R, and On Demand or streaming selections, giving people one shot to catch the program as it aired in real time. Nielson numbers were vastly different as well. If a program catches ten million viewers today, its considered a success, whereas, almost three times as many people were tuning into television shows in the seventies.

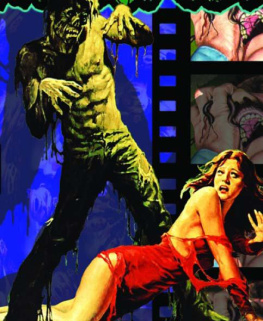

But aside from tailoring the TVM as event programming, it inadvertently served another purpose. For audiences who did not have the luxury of living in a major city, this particular era of the telefilm became a looking glass into the world of genre cinema. Largely considered the bastard stepchild of its silver screen counterparts, the made for television movie shared much with the drive-in and grindhouse theaters: TV movies also wrangled with low budgets, slumming film stars and tight shooting schedules. If not working outside of the rules, the telefilm still found ways around them, often creating stark messages about the changes in the world around us. However, at the time, exploitation cinema was mostly the reserve of urban meccas that could entice a profit-making audience. Those of us left out of this movement of independent genre film instead had three networks competing for our time and attention. In the decadent seventies mass appeal exploitation topics such as hitchhiking, satanic creatures and voyeurism kept audiences glued to their seats. Regardless of whether the networks were eager to cash in on controversial subjects or had a more commendable notion in mind, these movies reflect an era, and serve as a boob-tubed time capsule for a generation who recall many of these telefilms fondly.