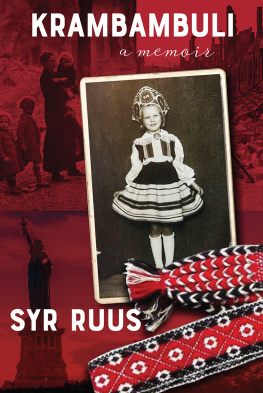

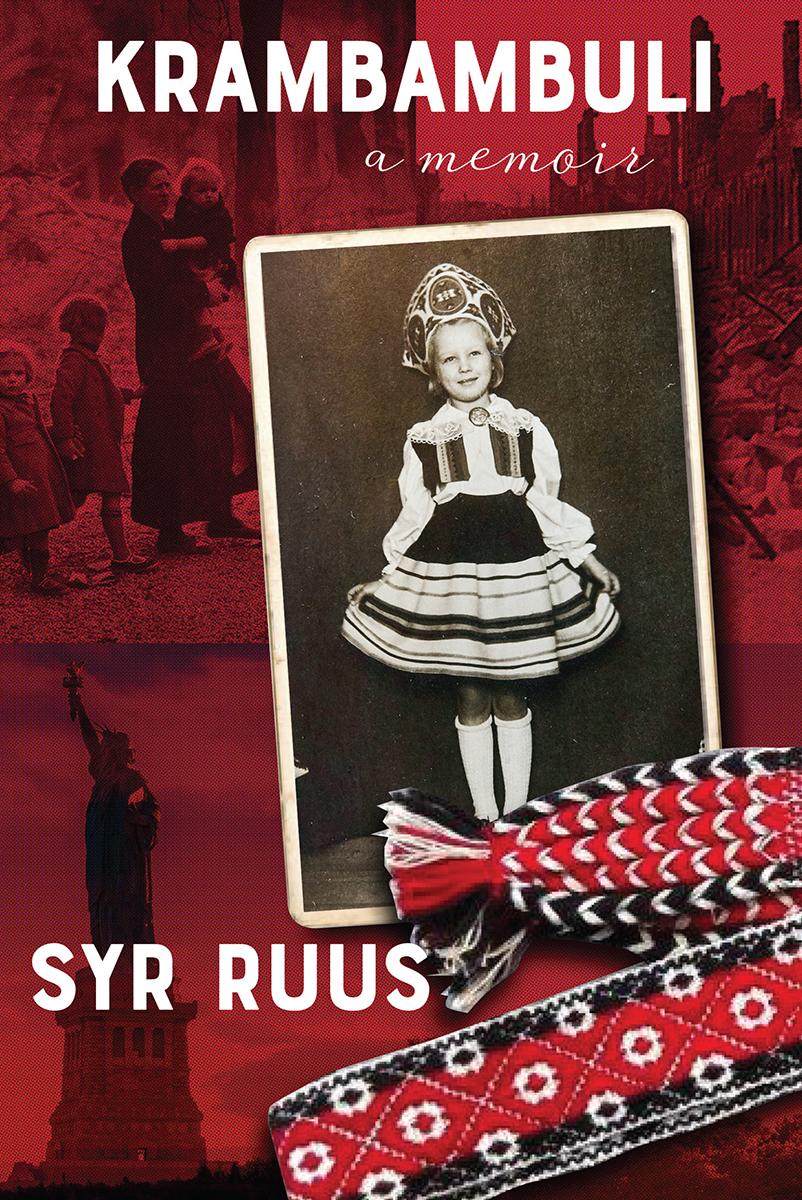

KRAMBAMBULI

Copyright 2018 Syr Ruus

Except for the use of short passages for review purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced, in part or in whole, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, including photocopying, recording, or any information or storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Collective Agency (Access Copyright).

Published in Canada by

Inanna Publications and Education Inc.

210 Founders College, York University

4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3

Telephone: (416) 736-5356 Fax (416) 736-5765

Email:

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.

Printed and Bound in Canada.

Cover design: Val Fullard

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Ruus, Syr, author

Krambambuli / Syr Ruus.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77133-573-7 (softcover).-- ISBN 978-1-77133-574-4 (epub).--

ISBN 978-1-77133-575-1 (Kindle).-- ISBN 978-1-77133-576-8 (pdf)

1. Ruus, Syr. 2. Ruus, Syr--Childhood and youth. 3. Ruus, Syr--Family. 4. Authors, Canadian (English)--Biography. 5. Refugees--Estonia--Biography. 6. Refugees--Germany--Biography. 7. Refugees--Austria--Biography. 8. Immigrants--United States--Biography. 9. Immigrants--Canada--Biography. I. Title.

PS8635.U96Z465 2018 C818.603 C2018-904376-8

C2018-904377-6

KRAMBAMBULI

A MEMOIR BY

SYR RUUS

For every person

who has been displaced by war.

Krambambuli

The finest brew

To ever foam inside a glass.

Is that so?

We ought to know!

Thats why we sing

Krambambuli.

KRAM-BIM-BAM-BAMBULI

KRAM BAM BU LI

Seventeenth-century German drinking song translated from the Estonian by the author

Overture

M Y MOTHER, EMA, PURSES HER LIPS and waggles her head at me in irritation. She is eighty-two. I am fifty-six.

Perfumed and powdered, with her hair styled into a smooth grey bob and her well-manicured fingernails a more subdued shade than I remember, she is cloaked in a silk ensemble of large pink roses. A flower among flowers , she jokes, smiling five-thousand-dollar bridgework. A gallery is showing twenty-seven of her most recent watercolours. Lilacs has already sold before the official opening. She is pleased with herself. And with good reason. Ema is a survivor, able to skim graciously over the surface of life by eliminating the past, refusing to speak of it, and, with luck, never thinking about it either. Cant you remember anything pleasant about when you were a child? she asks.

Yes, Ema, I do remember. And so I write

I am cutting out pictures from a discarded newspaper to serve as paper dolls. It is difficult to find a photograph with all the limbs intact. Often parts of arms are gone and both legs are missing from the knees down. The photos are mostly of grown-ups; children are harder to find. I press the cut-outs carefully, like fragile flowers, between the pages of an old copybook I have labeled HOCHFELD 237, AUGSBURG, DEUTSCHLAND. This was our address in the Displaced Persons Camp where we lived from 1946 to 1949, before we came to America. I call it my tenement book.

Newsprint is scarce, not a scrap wasted. You bring home whatever you can scavenge and allow me to cut out pictures before tearing the pages into small squares for the WC and demonstrate how to prepare the paper by rubbing it hard between the knuckles until it becomes soft enough for wiping.

I play paper dolls with my friend, Helle. She has some with all the limbs intact that she cut from an old fashion magazine. Somewhere, she even found a baby. My best dolls are: General Eisenhower wearing lots of medals on his chest with both arms and both legs, missing only his feet; the top halves of the Sun Maid Twins cut from the sides of the small box of raisins we got in a Red Cross package; and, best of all, Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, both intact and wearing their wedding outfits, which took up most of the newspapers front page on November 21, 1947. I use a tiny folded scrap of light blue paper for their baby, pretending that he is wrapped in a blanket, and give them three pages of my HOCHFELD book to live in because they are royalty.

Helle is nine, older than me. She has chapped lips and a constant sniffle, even in summer, and lank brown hair that she chews on out of habit. She knows a lot about grown-ups and thinks up most of our games. We remove our dolls from their rooms between the pages of our tenement copybooks and pretend they attend choir practice or to go to the theatre or to parties. They also have fights and secrets and love affairs.

Helle and her mother live in the building next to ours, in a bigger room with three other women who stay up late at night smoking paberosse and playing cards. Her mother has a green eye and a brown one, but Helles are both grey with droopy lids, probably because she never shuts them so as not to miss anything thats going on even when shes supposed to be asleep. The men in her building make liquor in the cellar, and have parties where everyone gets drunk. You go there too, Ema. Do you remember? And you come back foolish. You lie in bed sick all the next day. Never again, you promise.

We are lucky to be in a room with just the two of us, you say, but I think Helle is luckier. She has more fun. Helle tells me that a man at her place kisses her and tickles her and lies down with her on her bed when no one else is around. He is in love with her, she says. He is eighteen. A grown-up.

In our unit, we share the kitchen and WC with an old couple who lives in the other small room across the hallway and with four young men in the large room next door. They were soldiers in the war like my father, Isa. Three are maimed, missing arms or legs. One is funny in the head. Whenever they are able to get liquor, they stay up all night, yelling or singing sad songs about the lost homeland. Afterward there is often vomit in the WC or in the hallway. I am supposed to stay away from them.

You dont like Helle either, I can tell. You would rather have me play with Annie-Mannie because you and Tdi Leena, Annies mother, are best friends. Tdi Leena has a tapeworm that lives in her stomach, and, whatever she eats, the worm gets most of it. We only have the little white worms. Everyone has those, you say.

Annie is not yet seven and doesnt know a lot of grown up stuff like Helle. She has a father and an older brother who is almost a man. Her mother calls her Annie-Mannie . We all make fun of her. Annie-Mannie! Annie-Mannie! Time to come in now, we taunt, and Annie goes home, crying. She is spoiled and tattles about everything.

Annie and I play paper dolls too, but not with cut-out people doing real-life things like with Helle. There is an older girl in Annies building who draws really well, and if we nag her long enough she makes dolls for us with her set of coloured pencils. When you and Tdi Leena get together to lay out cards for double solitaire, Annie and I draw dresses for these dolls, adding little tabs at the shoulders and waist and cutting slits in the hats so they stay on.