May 1945

A JEEP OF B RITISH SOLDIERS dropped him and Fishl at the edge of a large town, with a map, tins of food, half a loaf of bread, and a number of little amenities. Cigarettes. Almost better, a toothbrush for each of them. Identity papers, protected by a brown envelope. Pens. He could feel the shape of the good one in his breast pocket. He felt wary and afraid but almost relieved to be away from the soldiers, at least until they arrived at the refugee assembly center. It would have been better to be among the Americans, who had liberated him. He was not sure about the British, who shouted at him as if he were deaf, or a donkey. He could not yet speak the language, but he was not a donkey. He was not a donkey, although at times he still felt himself to be a zebra, what they called the men who had nothing but their striped prisoners uniforms. He wore clean clothes on his narrow shoulders, having organized for himself a used suit from an acquaintance who worked in the storehouse of clothing in the abandoned camp. He no longer looked like an animal. He no longer looked, but he felt: he was a zebra.

They shuffled through the gravel near a large villa, empty and quiet, perhaps belonging to a former Kommandant. Late spring rains had settled the dust from the rubble, making the roads easier to walk past the long gardens and toward the forest. It seemed to him they were walking quickly, but the sound of his footsteps came at a labored pace. His shoes were hard, their bottoms thick. He had hammered scraps of stolen rubber onto the wooden soles, for himself and for Fishl too. Still he could feel the sharp outlines of stone under his feet.

But the shoes were to him better than bread. At the thought of bread he felt his right knee tremble a little, then steady itself. These shoes could bring him to bread, could bring him to any provisions he could organize, could bring him to a resting place in the assembly center for the stateless, a days walk away. To clear his mind from bread he pressed his hand into his breast pocket and pulled out a cigarette. He let it hang from his mouth. He could wait before using one of his matches. Saliva welled around the corners of the cigarette, his stomach began to burn again with the sharp tang of hunger, but still it felt good to have something in his mouth, the almost-taste of the tobacco making him walk faster. In a moment Fishl too would take out a cigarette, and they would share a match.

They walked along the town outskirts, along the border between trees and road, ready to flee into the woods if anyone came after them. Newly liberated, this town, the British expanding their authority, the towns people quiet in their houses, afraid. He liked the idea of Germans waiting inside, not knowing who would knock at the door, drag the man of the house, or the mother or the child, into army headquarters for questioning or punishment. He liked the idea. Still the quietness bothered him. He and Fishl saw a young boy with a large dog playing in the road ahead of them. Without speaking to each other, they began moving deeper into the woods, walking slowly among the trees, seeing the road but not visible from it.

Under a wide plum tree they stopped and leaned against the bark. Now came time to strike the match, and the two of them inhaled the tobacco almost in unison. He looked at his fingers, holding the cigarette away from his mouth. His hands, always slender, looked not brittle but merely thin. Yes, he was stronger now. His hair grew back thick and dark, still short but beginning to curl. He felt the roughness around his chin and cheeks, and felt a shiver of relief: the British had let him use their basin for a shave only yesterday, and already he needed another. It was a healthy man who needed a shave every day.

He looked at Fishl pushing the last bit of the cigarette between his teeth. Perhaps another hour, and they would start to eat a portion of the provisions they had collected from the British. It was important to save. A man knew how to save, how to organize, how to maneuver. He knew Fishl thought the same way. Before the war, he and Fishl had lived in neighboring cities, and their girlfriends had been close; they knew each other only slightly then, trading pleasantries in the same dialect of Yiddish. But now it was as if they had had the same parents, the same home. They were like brothers, a new kind of brother.

J UST THREE WEEKS BEFORE the liberation, convinced they were all to be shot, the two of them had cut through the electrical wire near their work barracks during a blackout and escaped to hide in a deserted farmhouse, one sleeping while the other kept watch. In the beginning, still weak, they had hidden in the barn of a farmhouse until the house was requisitioned by the soldiers, Americans with their shocked faces, equipped with a soldier or two who could translate from German. It was rumored that soon the Russians would come, hunting for women. He and Fishl knew to leave. They had refused to return to the camp, converted from a prison into a refuge. Instead the two of them had moved to the floor of an empty schoolhouse, sleeping, with dozens of others, men and women together, in disinfected military blankets. The soldiers fed them. Not too much, but more than the liberated prisoners received in the camp. People there still died every day, hungry, sick, encircled by wire and guarded by the conquering armies afraid to let the prisoners out into the world, afraid the hunger and sickness would spread and infect. But from the moment the liberators arrived he made sure they understood what he was made of. He would work and learn. He made chess pieces from discarded bits of metal found in the former camp factory, and sold them in sets to the young soldiers, who drew out the grids of a chess game on a bread board or lumber scrap taken from a German family. Yes, a human could make something out of anything, could make the ugliest of objects into a source of pleasure. He still ate the bread they gave him too quickly, he still made a rattle when he scraped the bottom of his bowl with his army-issued spoon, he still craved what the soldiers themselves ate, their meat and their eggs and their milk, but he knew he was coming alive.

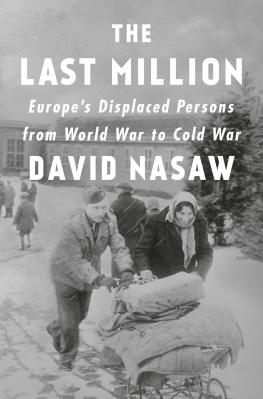

W ALKING AMONG THE DARK trees, they heard a steady rhythm behind them, footsteps, the slow turn of wheels. They turned. Two men in wool coats, seeming even from a distance to sweat, each dragging behind him a loaded wagon. The wheels of the wagons caught on the tree roots, and the men pulled with their necks bent forward, their shoulders straining ahead of their legs, bodies at a diagonal. They looked like children, small boys playing at a race. But they were men. Not strong, but men. Middle-aged, perhaps office workers, functionaries, Germans.

The Germans stopped moving. He could feel Fishls breath turn warmer next to him. An idea with no words ran through his head and pushed his legs forward. He saw Fishl move his hand into his pocket, the pocket with the knife. They went slowly toward the Germans, and he could feel the same rage pulsing between him and Fishl, and without even opening their mouths to speak they knew they were right: the wagons were filled with valuables, money, bagfuls of reichsmarks, gold and silver finery. The men trembled and begged as they gave up their watches, their rings, and their stolen jewels, they looked at the two thin Jews as if it were they, he and Fishl, who were killers. Even as he concentrated his mind on keeping the fury inside his body, he could understand how funny it was, these men in their uniforms, fat men, afraid of former prisoners who perhaps could denounce them, prisoners with one knife between them, liberated prisoners still in their cage of hunger.