Yes, Chef is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

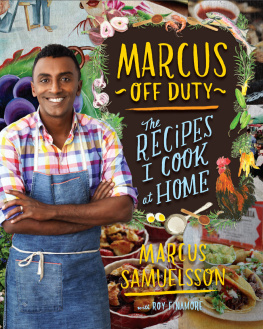

Copyright 2012 by Marcus Samuelsson Group LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Alfred Publishing Co, Inc. for permission to reprint an excerpt from Take the A Train, words and music by Billy Strayhorn, copyright 1941 (Renewed) by BMG Rights Management (Ireland) Ltd. (IMRO) and Billy Strayhorn Songs, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by Chrysalis One Music (ASCAP). All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Samuelsson, Marcus.

Yes, chef / Marcus Samuelsson.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-440-33881-9

1. Samuelsson, Marcus. 2. CooksUnited StatesBiography.

3. African American cooksUnited StatesBiography.

4. Swedish AmericansBiography. I. Title.

TX649.S226A3 2012

641.5092dc23

[B]

2011042220

www.atrandom.com

Cover design: Anna Bauer

Lettering: Chelsea Cardinal

Cover photographs (top to bottom): Bobby Fisher, courtesy of the author, Kwaku Alston

v3.1_r1

Chant another song of Harlem.

Not about the wrong of Harlem.

But the worthy throng of Harlem.

Proud that they belong to Harlem.

They, the overblamed in Harlem,

Need not be ashamed of Harlem.

All is not ill-famed in Harlem.

The devil, too, is tamed in Harlem.

A NONYMOUS , circa 1925

Contents

PART ONE BOY

ONE MY AFRICAN MOTHER

I HAVE NEVER SEEN A PICTURE OF MY MOTHER .

I have traveled to her homeland, my homeland, dozens of times. I have met her brothers and sisters. I have found my birth father and eight half brothers and sisters I didnt know I had. I have met my mothers relatives in Ethiopia, but when I ask them to describe my mother, they throw out generalities. She was nice, they tell me. She was pretty. She was smart. Nice, pretty, smart. The words seem meaningless, except the last is a clue because even today, in rural Ethiopia, girls are not encouraged to go to school. That my mother was intelligent rings true because I know she had to be shrewd to save the lives of myself and my sister, which is what she did, in the most mysterious and miraculous of ways.

My mothers family never owned a photograph of her, which tells you everything you need to know about where Im from and what the world was like for the people who gave me life. In 1972, in the United States, Polaroid introduced its most popular instant camera. In 1972, the year my mother died, an Ethiopian woman could go her whole life without having her picture takenespecially if, as was the case with my mother, her life was not long.

I have never seen a picture of my mother, but I know how she cooked. For me, my mother is berbere, an Ethiopian spice mixture. You use it on everything, from lamb to chicken to roasted peanuts. Its our salt and pepper. I know she cooked with it because its in the DNA of every Ethiopian mother. Right now, if I could, I would lead you to the red tin in my kitchen, one of dozens I keep by the stove in my apartment in Harlem, filled with my own blend and marked with blue electrical tape and my own illegible scrawl. I would reach into this tin and grab a handful of the red-orange powder, and hold it up to your nose so you could smell the garlic, the ginger, the sundried chili.

My mother didnt have a lot of money so she fed us shiro. Its a chickpea flour you boil, kind of like polenta. You pour it into hot water and add butter, onions, and berbere. You simmer it for about forty-five minutes, until its the consistency of hummus, and then you eat it with injera, a sour, rich bread made from a grain called teff. I know this is what she fed us because this is what poor people eat in Ethiopia. My mother carried the chickpea powder in her pocket or bag. That way, all she needed to make dinner was water and fire. Injera is also portable, so it is never wasted. If you dont finish it, you leave it outside and let it dry in the sun. Then you eat it like chips.

In Meki, the small farming village where Im from, there are no roads. We are actually from an even smaller village than Meki, called Abrugandana, that does not exist on most maps. You go to Meki, take a right in the middle of nowhere, walk about five miles, and that is where we are from.

I know my mother was not taller than five feet, two inches, but I also know she was not delicate. Those country women in Ethiopia are strong because they walk everywhere. I know her body because I know those women. When I go there now, I stare at the young mothers to the point of being impolite. I stare at those young women and their children and its like watching a home movie that does not exist of my childhood. Each woman has a kid, who might well be me, on her back, and the fingers of her right hand are interlocked with another slightly older kid, and that kid is like my sister. The woman has her food and wares in her bag, which is slung across her chest and rests on her hip. The older kid is holding a bucket of water on her shoulders, a bucket thats almost as heavy as she is. Thats how strong that child is.

Women like my mother dont wear shoes. They dont have shoes. My mother, sister, and I would walk the Sidama savannah for four hours a day, to and from her job selling crafts in the market. Before three p.m. it would be too hot to walk, so we would rest under a tree and gather our strength and wait for the sun to set. After eight p.m. it was dark and there were new threatsanimals that would see a baby like me as supper and dangerous men who might see my mother as another kind of victim.

I have never seen a picture of my mother, but I know her features because I have seen them staring back at me in the mirror my entire life. I know she had a cross somewhere near her face. It was a henna tattoo of a cross, henna taking the place of the jewelry she could not afford or even dream of having. There was also an Orthodox cross somewhere on the upper part of my mothers body, maybe on her neck, maybe on her chest, near her heart. She had put it there to show that she was a woman of faith. She was an Orthodox Ethiopian Christian, which is very similar to being Catholic.

I dont remember my mothers voice, but I know she spoke two languages. In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois spoke of the double consciousness that African Americans are born into, the need to be able to live in both the black world and the white world. But that double consciousness is not limited to African Americans. My mother was born into it, too. Her tribe was a minority in that section of Ethiopia and it was essential to her survival that she spoke both the language of her village, Amhara, and the language of the greater outside community, which is Oromo. She was cautious and when she left the Amharic village, she flipped that switch. She not only spoke Oromo, she spoke it with a native accent.