Contents

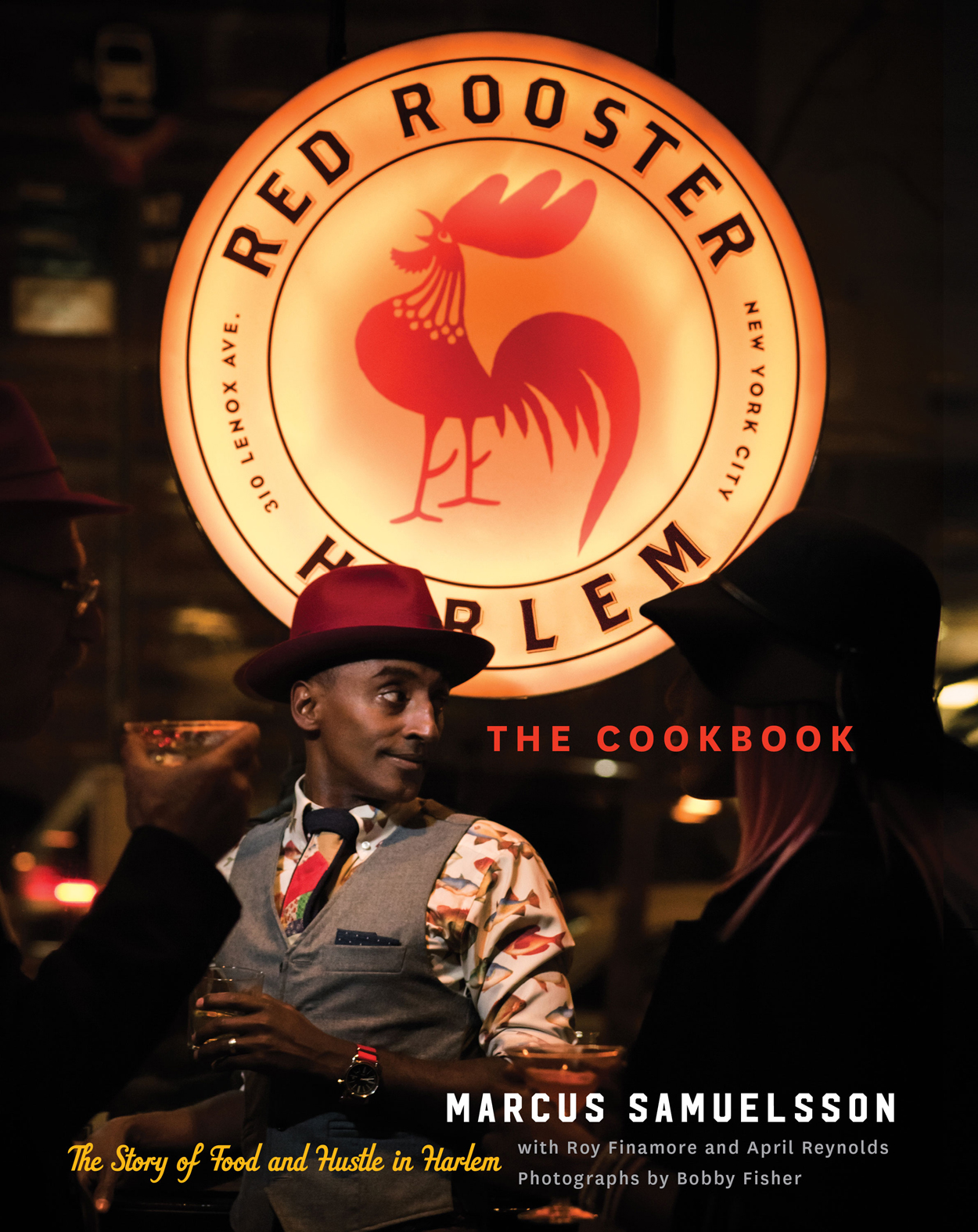

Copyright 2016 by Marcus Samuelsson Group LLC

Foreword 2016 by Hilton Als

Photographs 2016 by Bobby Fisher

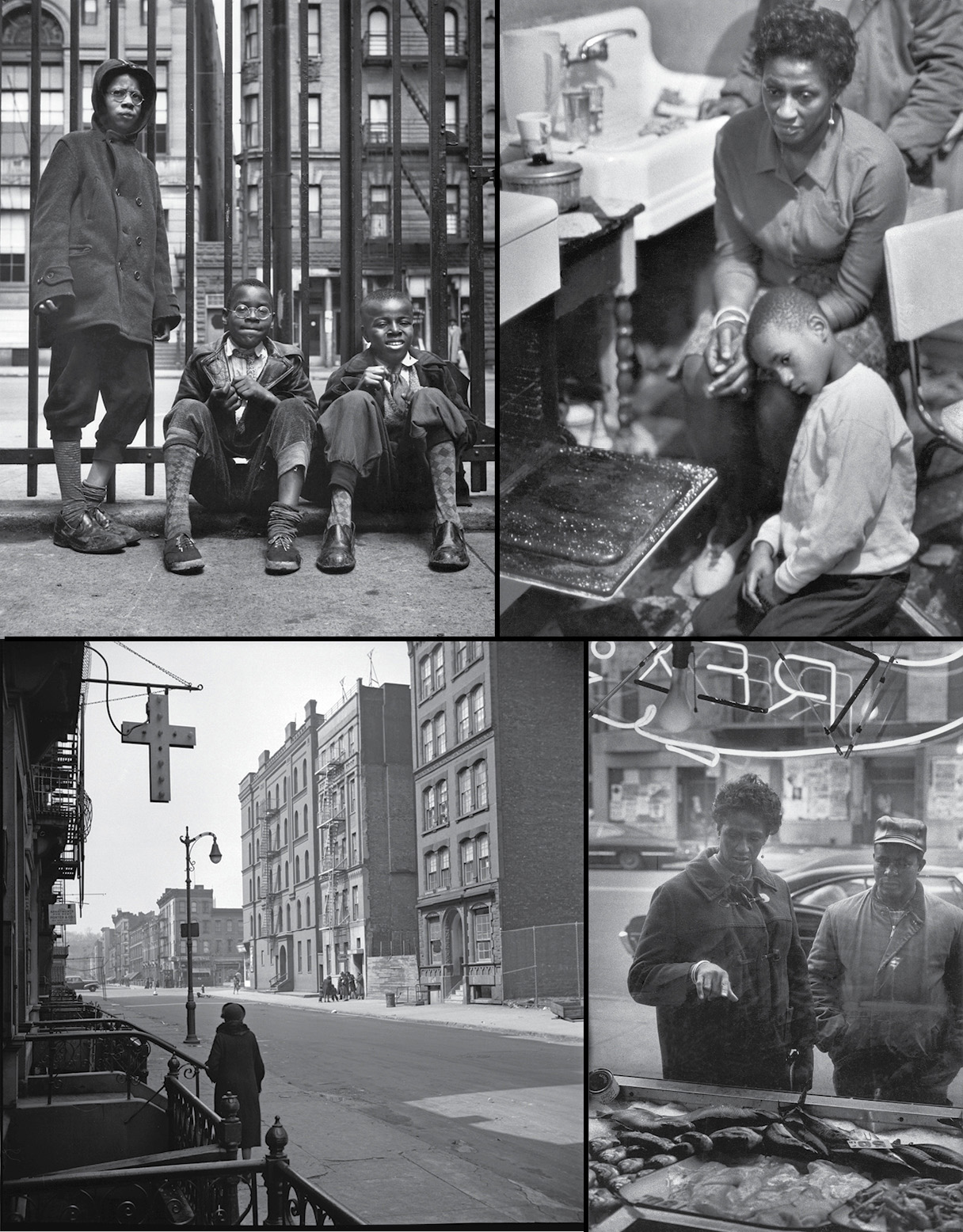

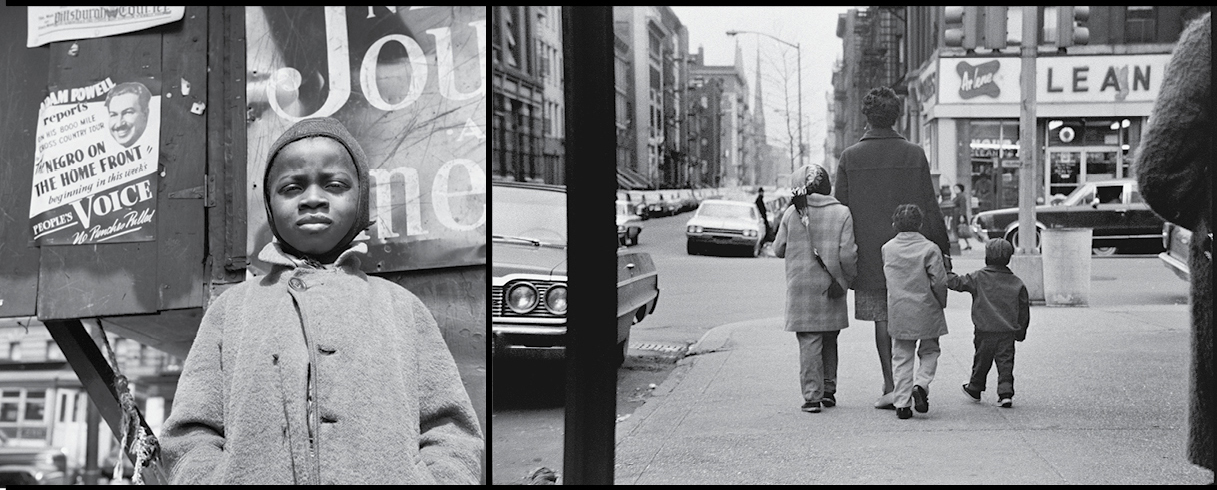

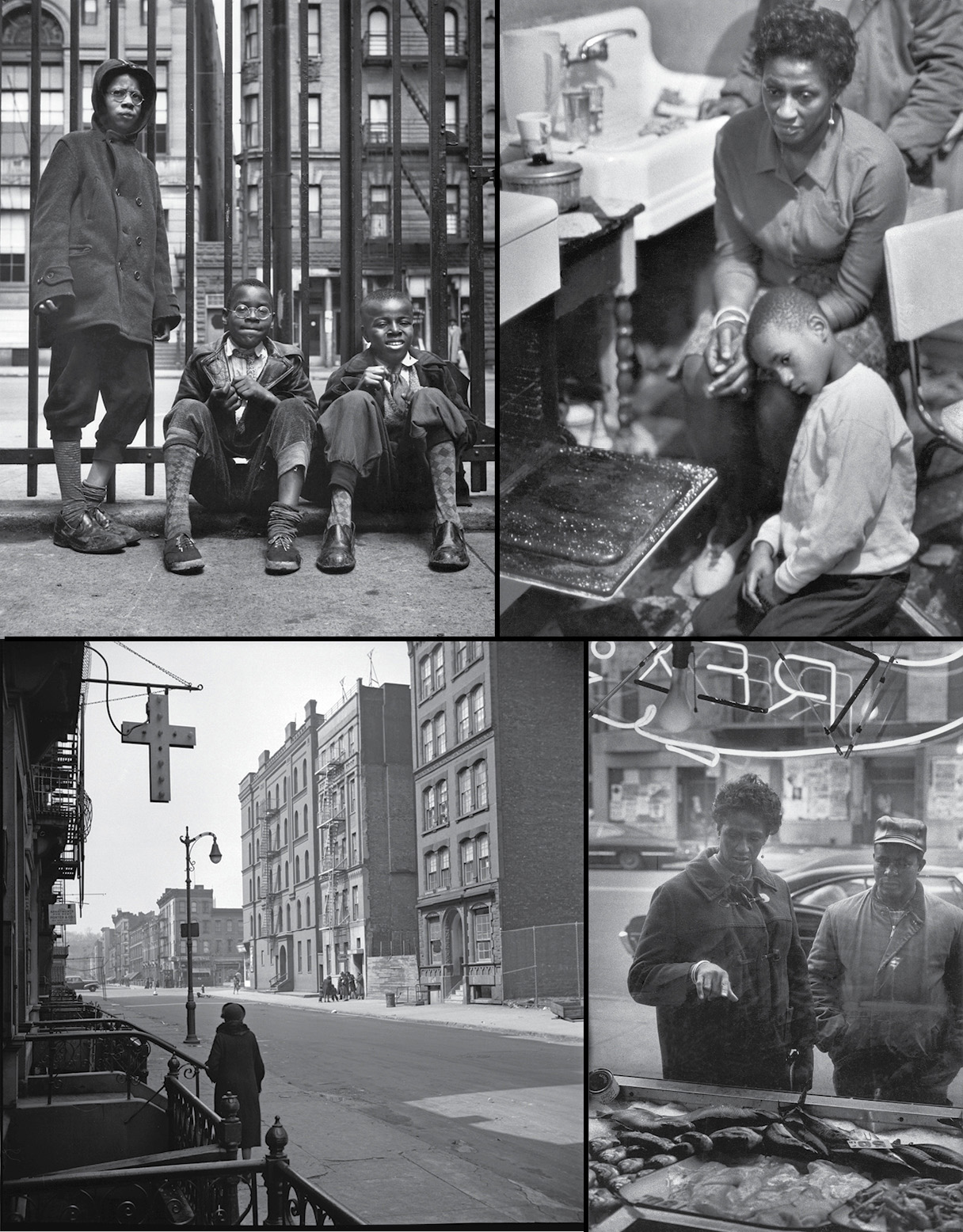

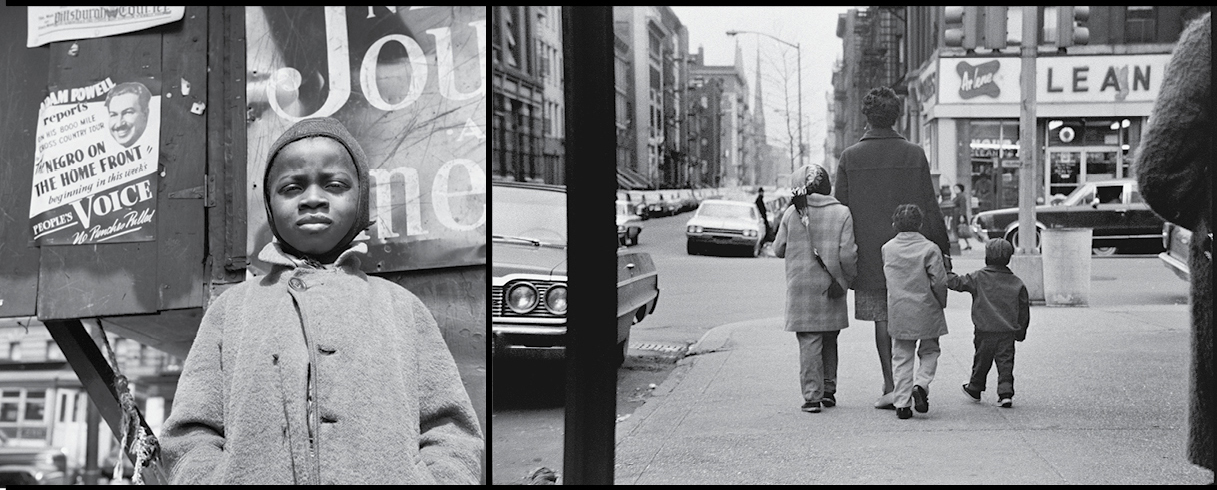

Historical photography on pages by Gordon Parks, courtesy of and The Gordon Parks Foundation

Illustrations 2016 by Rebekah Maysles and Leon Johnson

Background image Reinhold Leitner/Shutterstock.com

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-0-544-63977-5 (hardcover);

978-0-544-63981-2 (ebook)

Book design by Toni Tajima

v1.0916

To the people of Harlem, especially the generation before mine who cared, restored, and fought for uptown, to make sure Harlem would be a special neighborhood in the greatest citya place I am lucky to call home.

Contents

Acknowledgments

THE FIRST THANKS ARE TO MY WIFE, MAYA, for allowing us to cook up a mess in the house. Without all your support in the Rooster journey, none of the eating, drinking, cooking, mixing, and celebrating would be possible.

And to the Samuelsson tribe, here and abroad, for your love, guidance, and support in all things I do.

Thank you to Rux Martin and everyone at HMH who have believed in this book since before the days of Off Duty .

Thank you to April Reynolds for your time, energy, and words. You brought this story to life and your dedication shines through.

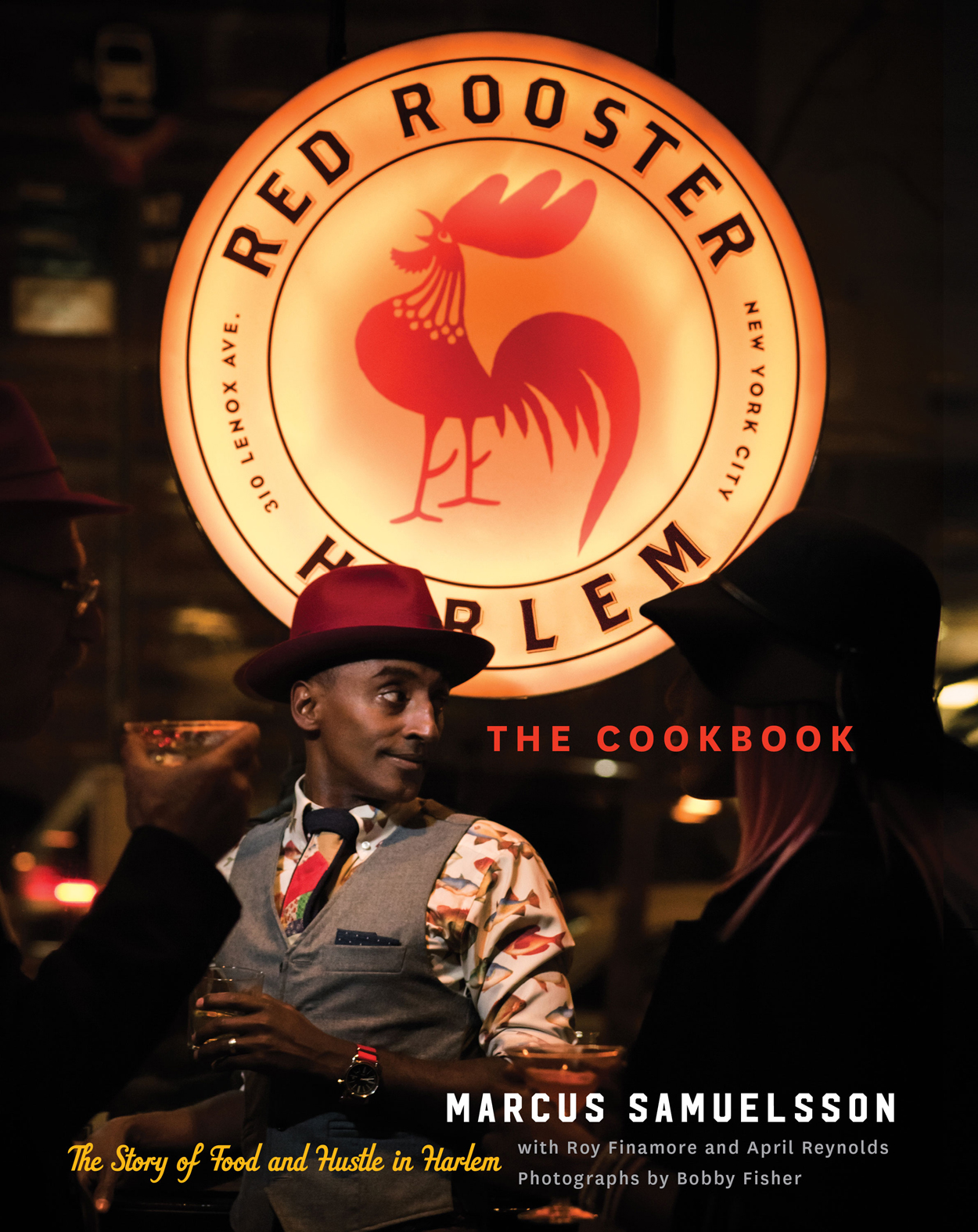

Thank you to Bobby Fisher, for bringing my neighborhood alive on the page. Your bold vision, patience, and keen eye have taken this book to the next level.

Thank you to Roy Finamore, for being our recipe mastermaking sure every single bite of this book is tasty, every time.

Thank you to Ashley Bode, for your tireless work and dedication.

Thank you to Kim Witherspoon, Leslie Stoker, Victoria Granof, Olivia Anderson, and Nick Krasznai, for making this book beautiful and delicious from cover to cover.

Thank you to my Marcus Samuelsson Group family, for carrying the torch and enjoying the ride. And to Derek Evans, Howard Greenstone, Jeanette Cebollero, Jori Carrington, Jeannette Park, Meaghan Dillon, Erica Morris, Stacy Rudin, Jenn Burka, Angela Bankhead, and Jono Gasparro. To Derek Fleming, Nils Norn, Tracey Kemble, Mahir Hossein, Christina Wang, Jane Ren, Marisa Blanc, Raul Adorno, and Eden Fesehaye, for getting this family started.

Thank you to my Rooster crew, past, present and future, for making this place feel like home. And to my chefs, Patricia Yeo, Adrienne Cheatham, Charlene Johnson, Kingsley John, and Cyed Adraincem, for making delicious food every day that fuels the fire of the Roo, and Lissette Tabales, for your expert mixology and keeping everyone in the bar happy.

Thank you to Andrew, Richard, and the Chapman family, for helping me create something so much more than a restaurant.

Thank you to Dapper Dan, Lana Turner, Bevy Smith, Mayor Dinkins, Marjorie Eliot, Tru Osborne, Rakiem Walker, Kim Hastreiter, Nate Lucas, Billy Mitchell, Thelma Golden, Melba Wilson, and my Harlem neighbors, for lending us your stories and telling us how it really is.

Thank you to Elizabeth Johnson, Sidra Smith, Christina Scott, Cody and Tash, The Rakiem Walker Project, Louis Johnson, Christian Lopez, Daniel Jeffries, AnhDao Nguyen, Fatima Glover, Ulrika Bengston, Angela DiSimone, David Melendez, Ezelia Johnson, and all the others for being the stars in our photos.

Thank you to Gillian Walker and the Maysles family, for letting us stir up trouble in your kitchen and to Rebekah Maysles, for not just her beautiful illustrations but also her stories and friendship.

To the Harlem cooks that came before, Sylvia Woods, Pig Foot Mary, Charles Gabriel, and Crab Man Mike, for showing us all how hospitality should be.

Thank you to The Gordon Parks Foundation, for loaning their iconic images and bearing witness.

Foreword

Hilton Als, writer and critic for The New Yorker, reminisces about his childhood visits to Harlem and how art, music, and food lured him back to this legendary neighborhood.

FIRST WHAT WE WOULD DO was collect glass Coke bottlesthis was in the late nineteen-sixties. You could get refund money for that, a few pennies for each bottle, but that added up. I would put my little brother in the red wagon we both owneda gift from our father, who didnt live with usand then Id load the wagon up with Coke bottles, the baby and glass bottles clanging delightedly on their way to the store. Then, once the cart was clear, Id pool my money with my tough first cousin, Donnashe was five years older than me and when big boys bothered me, she beat them upand then, when we had enough dimes and nickels and pennies rolled up, wed sneak away from Brooklyn, where we lived, and take the A train all the way to Manhattan and the Apollo, to see James Brown. We werent allowed to go so far on the train on our own, but we lied, somehow, and once divested of the burden of the truth, there Donna and I would be, sporting our naturals, Donna, the teenager, grown-like and smoking a cigarette, standing with me in the balconywho could keep still?enthralled by rhythms and the feelings rhythms generate, all produced by a genius who spared no physical or psychic expense to express his art, and how our collective heart fit into it. This celebration of bodies and soundwe were one with the Apollo audience; we were the body James wanted to wrest love fromwas my first visit to Harlem, and after that Harlem was always one body to me, a beautiful black mass with many questions, including what was its relationship to the rest of the city, the nation as a whole, all those places outside Harlem that, in the nineteen-seventies, didnt give a shit about the neighborhoods fabled past and raggedy present, while Harlem, one black body, fought for, and sometimes won, a kind of self-conferred dignity. While James sang, Say it loud, Im black and Im proud!, and we did because thats the way we felt in our naturals and dashikis, it was something we had to fight for, too, and I remember after seeing James Brown at the Apollo, that I would then go uptown with my older sister, Bonnie, to demonstrate at what was called the sitethis was in the nineteen-seventiesan area of Harlem we were trying to save, we didnt want the government to build on it, and we would sleep on the ground with so many other people, all in front of where the State Office Building now stands, President Clinton has his office there now, and what I remember most about that experience is how our collective black body tried to stop that which could not be stopped but we tried anyway.