SANIA SHARAWI LANFRANCHI is a freelance interpreter, and has worked for international, regional and national organisations, including the Library of Alexandria and the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She holds postgraduate degrees in both English Literature and Arabic Literature from the American University in Cairo.

To my sister Malak

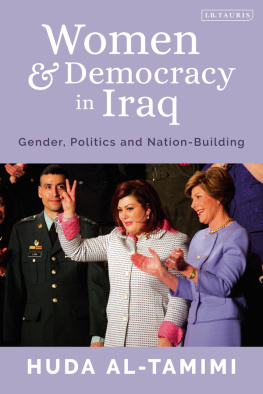

Published in 2012 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright Sania Sharawi Lanfranchi 2012

The right of Sania Sharawi Lanfranchi to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 84885 719 3

eISBN 978 0 85773 777 9

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record for this book is available from the

Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available

Contents

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

The great West-African writer Hampt-B said that the death of an old man is like a library set on fire. It is true that oral history is as vital to human experience as written history. I therefore wish to address posthumous thanks and gratitude to Cza Nabarawi, Hawa Idris, Huria Idris-Shafik and her husband Hasan Shafik, to Sherifa Lutfi Mehrez, to Eva Habib al-Masri, to Doria Shafik, to Suza Khulusi, to Jazbia Saad al-Din, to Fathia Abd al-Raziq, and to my mother Munira Asim, for their willingness to speak openly about their lives and experience with me since my early adolescence. Their memories were added to the discoveries I otherwise made in my grandmothers mansion. I wish to thank posthumously Gabrielle Rousseau-Fahmi, Jeanne Marqus, Mary Kahil and all the women who regularly came to the house and sat with the family long after Huda Shaarawis demise, for all the stories they passed on to me. My memory takes me to Dame Margery Corbett-Ashby and her wonderfully spontaneous granddaughter Charlotte, with whom I spent some time when they came to Cairo. Dame Margery entertained me much later in Horsted Keynes, where we talked for long hours about my grandmother and she honoured me by calling herself my English grandmother. I similarly wish to thank Dr John Von B. Rodenbeck and Dr Afaf Lutfi al-Sayid for their precious advice on the manuscript, as well as Dr Malak Badrawi for bringing some invaluable references to my attention, and Dr Aida Graff for a providential addition to my sources. Thanks are also due to Maria Marsh for following this book in in its various phases, and very special thanks to Gretchen Ladish and Robert Hastings for their exacting contribution and for having turned a history book into a work of art. I wish to thank Dr Margot Badran for her charming translation of Huda Shaarawis memoirs, which my grandmother asked her faithful secretary, Abd al-Hamid Fami Mursi, to write for her. Dr Badran also showed a passionate interest in the history of Egyptian and Arab feminists in her other works, and should be thanked for fulfilling the difficult task of writing extensively on the subject. Last but not least, I wish to thank all my sisters and brothers for sharing their memories with me and my children for their unfailing support and enthusiastic interest in my familys history.

Note on transliteration

Arabic words are usually transliterated, or rather romanised, according to the Western language in which the story is written. The French pronunciation and spelling, for example, are different from the English.

I have adopted a transliteration system mostly based on the use of the three Arabic vowels the letter aleph and the fatha are conveyed by a; the letter yaa and the kasra are conveyed by i, and the letter wow and the damma are conveyed by u. Furthermore, q replaces k to convey the guttural Qaf in Arabic. This unfortunately means that the letter y is not used at all.

In older times, in both daily life and in the magazine Lgyptienne, as well as other publications, the French spelling of names was adopted, so that Huda Shaarawis full name was Hoda Chaaraoui and Asim, up to the present day, is usually spelt Assem. The same system has been followed in this book for all the names of Arab characters, places or institutions. The Arabic ayn and the hamza, represented by and , respectively, have been deleted when possible (for example, Ali or Umar). All long vowels have been omitted. No distinction is made between the Arabic consonants zein and za, which are both transliterated as z, or sad and sin, which are both transliterated as s. My goal throughout has been to simplify the spelling of Arabic words and to eliminate diacritical marks in order to avoid confusing readers unfamiliar with Arabic. Well-known geographical place names (such as Cairo) and words with familiar spellings (such as pasha) have been retained, but less well known place names and words have been transliterated in accordance with the rules I have adopted. In the odd case, where a quotation from a text has used a certain form for a proper name, or where I know the persons preference in spelling his name, I have retained it. Ains and hamzas have been included in titles of books and in quotations, but all other diacritical marks have been omitted. The ta marbuta of words in a construct state is written as t at the end of the word.

Childhood in a conservative home

H uda Shaarawi was born on 23 June 1879. Her name at birth was Nur al-Huda Sultan. Her father, Muhammad Sultan Pasha, who was 55 when his daughter came into the world, was a man of substantial influence in Egyptian society and political life. An Egyptian from Minya, in Upper Egypt, where he had extensive estates, he was an extremely rich man accustomed to deference. In the way Egyptians have of conferring nicknames on important people, Sultan Pasha was widely referred to as the King of Upper Egypt. Wilfrid Blunt, an English resident who knew Egypt well and was a sympathiser with the Egyptian nationalist cause, observed that Sultan Pasha was a proud man of great wealth and importance and used to being given the first place everywhere. Hudas mother, Iqbal, by contrast, was of Circassian origin, the daughter of a family from the Shapsigh tribe of Dagestan. Her origins were both obscure and romantic, and she was scarcely 20 when Huda was born. Hudas brother Umar was born two years later, in 1881.

Iqbals own story was a romantic one. She was a proud and reticent woman who had been brought to Egypt as a child, and Huda only gradually pieced together her tale, learning much when she eventually met her mothers brothers. Iqbals father, reputedly a tribal chieftain, had been killed by the Russians during the Russian invasion of the Caucasus, and his widow, Aziza, had fled to Istanbul with her remaining family, including Iqbal. As refugees, the family suffered terrible hardship. One son died, and Iqbals baby sister was abducted by her wet nurse. When Iqbal was nine, Aziza decided to send her for safety to Egypt, a country she had never visited, under the protection of an Egyptian friend who was travelling to Cairo. It can only be imagined what an act of blind faith this was, and how much Aziza must have feared for her daughters welfare. The intention was to place Iqbal under the care of a man Huda later came to understand from her own uncles accounts was her mothers maternal uncle, Yusuf Sabri Pasha, an officer in the Egyptian army and a member of Egypts Turco-Circassian elite. It happened, however, that Yusuf Sabri Pasha was absent on military duty in the Sudan. His wife, described as a freed slave of a member of the royal family, who was no doubt herself of Circassian origin, reacted badly to Iqbals arrival, refusing to receive her and declaring that her husband had no family in the Caucasus. Iqbal was therefore taken instead by her escort to the house of his own trusted friend, Ali Bey Raghib. Raghib Bey and his family cared for her. She was brought up with their daughter and learned to speak Arabic as well as Turkish. Yusuf Sabri Pasha evidently remained in contact with her, however, and she grew up to regard him and his family as her kin. Iqbal came to feel a special bond with Yusuf Sabri Pashas daughter, Munira Sabri, who was her cousin. When she was of a suitable age, Raghib Beys family set about finding a wealthy husband for the Circassian girl for whom they had cared. Iqbal had grown into an extremely beautiful young woman, and it was a stroke of good fortune for her that Sultan Pasha was seeking just such a woman as a consort. His first wife, Hasiba, had born him a son, Ismail, who had sadly died not long before, and she had evidently lapsed into depression.

Next page