BRITISH MOTORCYCLES

OF THE 1960s AND 70s

Mick Walker

The long-established AMC (Associated Motor Cycles) had its origins back in 1901, when the Collier family produced their first Matchless machine for sale. But by the beginning of the 1960s AMCs problems were mounting. The bike shown is a 1962 Matchless G2CSR two-fifty.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

The 1961 Matchless 31 CSR 650cc.

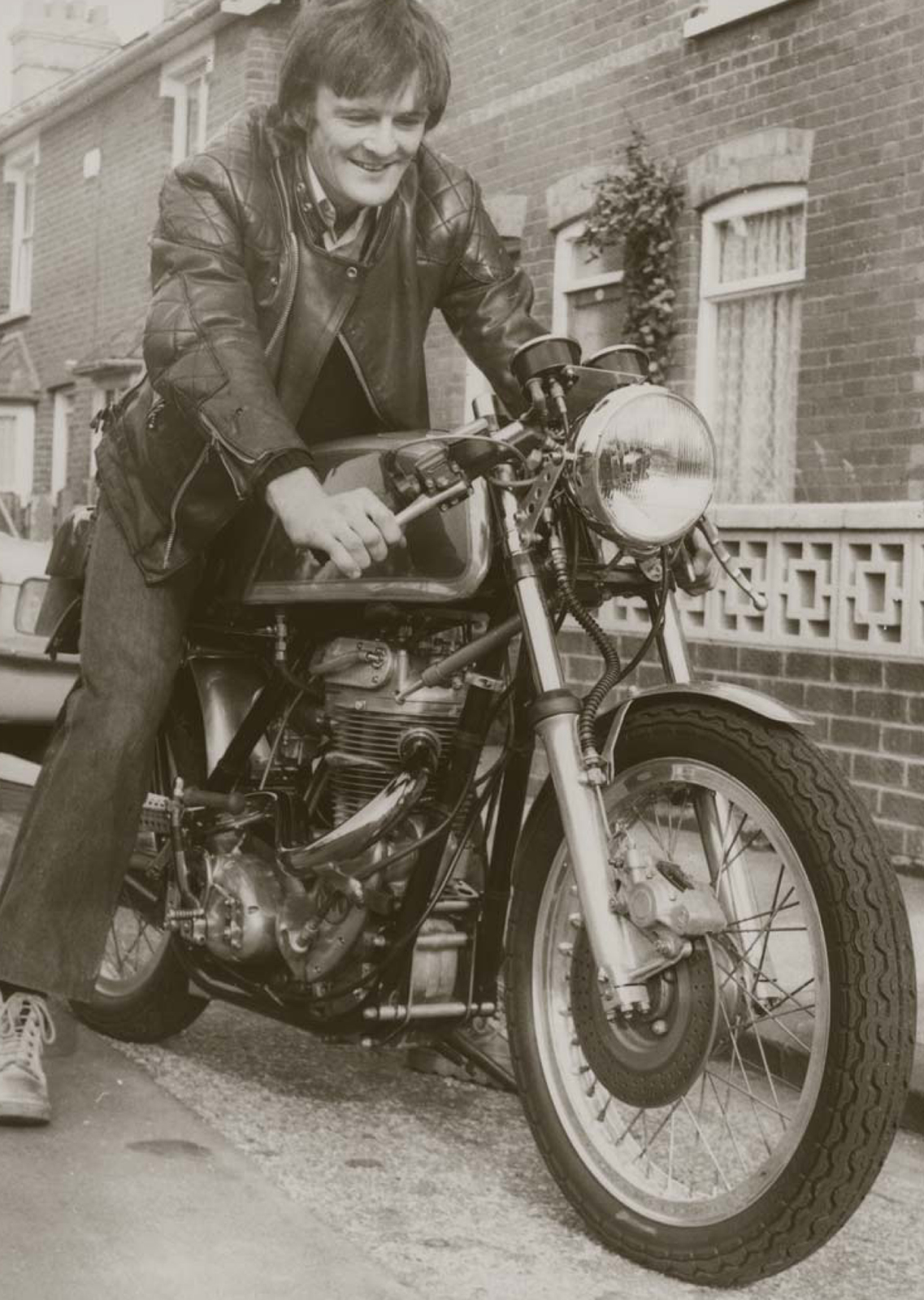

Nortons 750 Atlas used the same basic engine as the Commando model. This photograph was taken in Kent and dates from 1967.

INTRODUCTION

I N 1959 British registrations of motorcycles reached a record of 331,806 machines, a figure that, regrettably, would never be achieved again. The British motorcycle industry seemed blissfully unaware of what the 1960s held in store for it. Warning signs had already begun to appear, such as the participation of the Japanese Honda works team in the Isle of Man TT races for the first time in June 1959, and the debut of an inexpensive small car, the Mini, but the industrys management took no real action.

Then there were the social changes. Following the end of the Second World War, large numbers of new housing estates had been constructed, together with factories, offices and other places of work. This rapid expansion had meant that for the first time many workers now had to travel considerable distances to their places of employment, and so personal transport became a big issue, as many of the new housing estates were not served by railways or bus routes. Before the war the humble pedal cycle had been a vital means of travelling the often short distance from home to work. But now the bicycle rapidly fell out of fashion, largely because, as journey distances, and wages, increased, mechanised transport became all-important. During the 1950s this usually meant two wheels either a moped, a scooter or a motorcycle. Also during the 1950s there had been credit squeezes, petrol rationing (due to the Suez crisis), and variations in the rate of purchase tax (the forerunner of VAT).

But by the end of the 1950s the vast majority of restrictions had been lifted and so came the record sales figures achieved in 1959. However, what many did not take into account at the time was that almost half of these sales were of imported (European) models, mainly mopeds, scooters and ultra-lightweight motorcycles. Although this was at the low-value end of the market, it was a portion of the industry that represented potential future expansion, but which, sadly, the British manufacturers chose largely to ignore. The new customers tended to progress naturally from a moped to a scooter, and finally to a motor car, as soon as their finances allowed.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s the scooter sector was the focus of a vibrant social scene. The scooter importers, led by Lambretta and Vespa, had been quick to encourage this, by fostering club runs, rallies and even competitive events. By contrast, the established motorcycle clubs were run by enthusiasts for enthusiasts, and did little to encourage new customers.

A March 1961 Ariel advertisement showing the range of twin-cylinder two-stroke models: Arrow, Leader, and Arrow Super Sports.

The Mini (soon to be followed by a range of other new small cars from rival manufacturers) almost overnight dealt a death blow to the previously popular sidecar outfit. It could be purchased for little more than the cost of a new large-capacity motorcycle, provided four-seat saloon-car comfort, and was also fun to drive, thanks to its excellent roadholding and cornering abilities. For the family, it provided all-year weather protection, something the traditional motorcycle sidecar combination was unable to match.

As the 1960s began, few people in Europe, or for that matter North America, had much knowledge of Japan, and they had even less idea of the challenge its motorcycle industry was capable of providing. But, as described in a later chapter, the Japanese, led by Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha, in a few years caused the once great British motorcycle industry to go into terminal decline.

The 650 Triumph Bonneville was the most popular British sports roadster of the 1960s; it was also very successful in long-distance endurance racing.

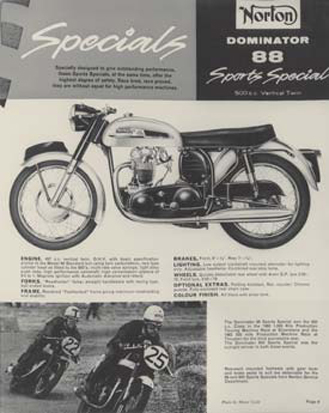

Brochure for the popular Norton Dominator 88 Sports Special; it won its class at the 1962 1,000-km production race at Silverstone and was also the class winner at that years Thruxton 500-mile race.

View of the BSA Small Heath factory production line during the mid-1960s. Machines are the 654cc Lightning twin-carburettor sports model.

The domestic British industry did not seem to appreciate the dangers it faced as it entered the decade that was to become known as the Swinging Sixties. It failed to realise that the Japanese would not be content in the long term to build and market only small-capacity machines, and the beginning of the end for the British motorcycle industry came in 1965 with the launch of the Honda CB450, soon nicknamed the Black Bomber. The threat from four-wheeled vehicles was also not fully realised, and another threat was the legislation being introduced by the British government to restrict new riders to a maximum of 250cc. This was a result of the large increase in learner riders during the 1959 sales boom; unfortunately, the big leap in sales had been matched by a correspondingly large jump in accidents. Yet another problem was the bad press caused by the rivalry between so-called Rockers and Mods, described in the next chapter.

The first series production British bike with five speeds, the Royal Enfield 250 Super 5, 1963.

One mans caf racer, essentially a Matchless G80 Scrambler with all-alloy engine, lightweight frame, 5-gallon alloy tank, disc front brake, high-level exhaust and clip-on handlebars (which attach individually to the top of each of the forks rather than forming one continuous handlebar).

CAF RACER CULTURE