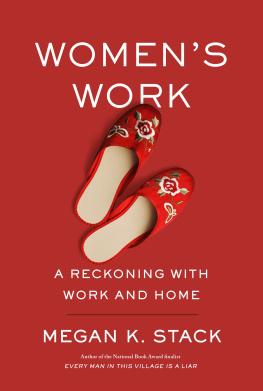

ALSO BY MEGAN K. STACK

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Copyright 2019 by Megan K. Stack

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Stack, Megan K., author.

Title: Womens work : a reckoning with home and help / Megan K. Stack.

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018035800 (print) | LCCN 2018038585 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385542098 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780385542104 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Stack, Megan K. | Child care workersIndia. | Child care workersChina. | Working mothersBiography. |

AmericansIndiaBiography. | AmericansChinaBiography.

Classification: LCC HQ 778.7. I 4 (ebook) | LCC HQ 778.7. I 4 S 73 2019 (print) | DDC 362.71/20954dc23

Authors Note

The experience of motherhood was eventually to radicalize me.

ADRIENNE RICH

I gave birth to my children in China and India. They are the sons of migrants, born into expatriationAmericans growing up in Asian megacities on the cusp of the Asian century. It wasnt my goal to have children overseas; it just happened that way. I got pregnant when I could and gave birth in the countries where I found myself at the time. I am a journalist and a writer. I didnt want to abandon my work for motherhood, and I didnt. Since my first baby was born, Ive written two books. This is one of them.

I wanted to keep working, and I wanted to have my children. It seemed simple before it began.

But then the babies were born. My husband came and went for work, traveling the way I had once traveled, the way we had once traveled togetheracross the country, around the world, bringing back the grains of roads Id never walked, the fading ghosts of spice and smoke rising from his skin. I stayed home with my children and my writing and the women who watched our children and cleaned our house so that I could keep writing. These women and I had little in common. They were poor women, brown women, migrant women. And at first I pushed them to the edge of thought. They were important to me, primarily, because they made me free. I wanted them to be happy. I didnt want to know the details. But that didnt work for long. The women were there. The women were here. We are here, together. I understood all too well the functional purpose of our arrangement, but I wasnt sure it made any sense.

Nor could I find the mess and nuance of our household reflected faithfully in any medium. Domestic workers are usually depicted in one of a few ways: essential financial investments made by guilt-free families; scrappy nafs cruelly exploited by the heartless, clueless rich; ormost insidiously, Ive come to thinklike family. Fundamental female experience is forever reduced to its crudest caricature. Childbirth is screaming. Periods are blood. Domestic work is a fairy tale: Cinderella under the thumb of a ruthless stepmother is finally living the dream when she becomes a benevolent princess with smiling servants of her own.

Gradually I realized that our house was an enclosed landscape of working mothers. That was the basic thing. The most important employees who worked for mewomen who shifted my thinking and cleared the way for my work and cared most lovingly for my childrenwere migrants whod left their own children behind to work in the city, and ended up in my house. We spun webs of compromise and sacrifice and cash, and it all revolved around memy work, my money, my imagined utopias of one-on-one fair trade that were never quite achieved.

When I was a reporter, there existed this clich about women who covered wars and other humanitarian disasters overseas. They used to sayand we used to say sometimes, toothat we were a sort of third gender. We couldnt dream of being men, of course, but we were also exempt from some of the constraints that bound the women we wrote about. We could bare our faces in the street or sit with the men at a segregated dinner. Maybe a commander who would never talk to a woman from his own country might grant us an interview. We were bridges between the tacit maleness of the news organizations that had sent us and the women who were affected by the news, the grieving mothers and worrying wives. We ourselves were neither here nor there.

No matter how much time I spent with a subject, no matter how intimate the interviews became, a yawning space separated me from the people I wrote about. They had one kind of life, and I had another. I was tethered to the concreteness of the newspaper, and to the abstractions of journalism. The particular troubles faced by women did not affect me, nor did my own personal struggles have anything to do with the women I was interviewing. I was just passing through.

After having babies, after raising children in close quarters with women I hired to help, this necessary distance began to warp and melt. I couldnt maintain the sense that I was going along and everything was just fine. It didnt seem fine. Sometimes it seemed crazy.

The immediacy of domestic life and the desperation of small humans left few opportunities to question our choices in real time. We stumbled confusedly through a house that was also a job site, grappling with the intimacy of underwear, bathrooms, feeding children, and cuddling them to sleep. Our routines were disrupted by pregnancies, abortions, miscarriages, weddings, domestic violence, funerals, sick children, and school fees. Mine, theirs. The stuff of women the world over. We lived together in the space left by men who were temporarily elsewhere. Men who beat and loved; disappointed and disappeared. The promise of men, the threat of men, the uncertainty of mens actions.

We lived those years in China, a rising superpower, and India, an emerging economic engine. These places represent our collective future; they are the stuff of the worlds dreams and nightmares. They are also places that have made statistical headway toward erasing women. Female fetuses are aborted. Newborn girls are murdered. Older girls are denied food. Female life is stifled before it can reach womanhood. This systematic erasure of women is not a government initiative, but a wildly popular and only semi-underground grassroots movement. And, of course, women participate.

Meanwhile, wethe women who occupied my housewere left to improvise, to endure what we could endure, to become as monstrous as we allowed ourselves to become. Our existence and interplays were literally intramuralbetween walls, among ourselves.

We were not unique. Our private problems are no doubt duplicated in households all over our planet. And yet housework is seldom considered as a serious subject for study, or even discussion.