Foreword

Robert Maynard Hutchins once famously remarked that whenever he felt the urge to exercise, he immediately lay down. Despite the hyperbole (for he, like Jim Watson, was an ardent tennis player) he had made the point that his priority resided in one relentless form of exercise, that of the mind. In this, too, Jim Watson is a true follower of Hutchins, as his book and indeed his life demonstrate so engagingly.

Under the leadership of Hutchins, the University of Chicago played a significant role not only in Jim's education, but as a permanent benchmark in his continuing thinking about education. If one of the principal goals of a liberal education is to leave students with an insistent lifelong preoccupation with the question of what education is for and what it is about, what qualities should characterize the truly educated person and what intellectual virtues should be sought and practicedand whythen Jim is a triumphant example of its success. Hutchins was the great critic of and innovator in twentieth-century higher education. He made his university the home of perhaps the most passionate debates over curriculum and intellectual purpose to take place in recent memory. And Hutchins, like Jim, was never satisfied: his university, he said, might not be very good, but it was the best there was. For undergraduates, the best had to do with a vision of general education that introduced students to the most profound questions of human life and civilization, and to the great writers and thinkers who had confronted and tried to make sense of theman education that taught students to think with rigor and integrity and to go on doing so under whatever circumstances they might encounter.

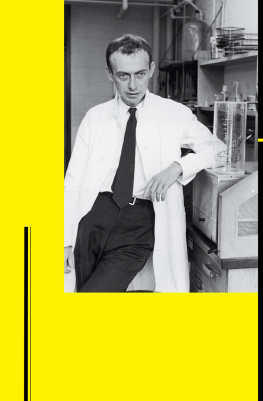

The budding ornithologist who entered Chicago's college left as a man ready to embark on the study of the gene, focused on an ambitious specialization while always underlining the need to sustain the widest possible intellectual curiosity. The imperative that Jim Watson had learned to embrace was to pursue the most difficult, perhaps intractable, problems and to think scrupulously and express his views honestly, whatever might be the consequences in terms of what is now called political correctness, other kinds of mere conformity and self-interest, or even politesse.

The austerity suggested by such an outlook does not, fortunately, preclude a fine sense for the enjoyment of the world, its pleasures and its foibles. Jim portrays himself as a very young and rather monastic undergraduate and as something of a late, and utterly enthusiastic, social bloomer. The freshness and candor of his observations on people and events, accomplishments and follies (including his own) may well derive from the novelty he found in every experience that, new to him, made life ever more interesting.

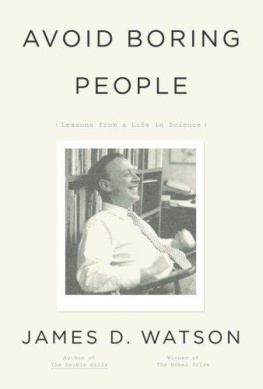

This combination of qualities shone through The Double Helix as it does here, and indeed Jim's account of the struggle to get the manuscript published more or less intact is almost as entertaining as the book itself. And just as The Double Helix became a classic in showing how science may really get done, so the present volume, in describing the whole trajectory of a unique career within a larger world of science and research, will join it and add to our understanding of Jim Watson's revolutionary achievements.

The different sides of Jim Watson's persona emerge vividly also from the remembered lessons detailed at the end of each chapter. Some may prove more useful than others. The advice to Expect to put on weight after Stockholm is not, alas, relevant for most readers, but Work on Sundays does have larger application. So, too, the wisdom of Don't back schemes that demand miracles.

The maxim Don't use autobiography to justify past actions or motivations defines the captivating tone of this autobiography and its direct self-revelation quite wonderfully. At the same time, the exhortation Avoid boring people is scarcely necessary, for if Jim Watson is incapable of anything, it is of boring people.

In consequence, we must all be grateful to Jim for so exuberantly following his own lesson: Be the first to tell a good story.

Hanna H. Gray, University of Chicago

Preface

Most of my unpublished writerly outputhandwritten manuscripts and letters, lectures and lab notes, university and government documents that I helped prepareis deposited in the archives of Harvard University and of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. In time, it will all become available to the public, mostly through the Internet, for those preternaturally curious about how I have moved through life. Rather than let other commentators have the first crack at those writings, I opted to be the first to employ them extensively to prepare this look at my life before middle age became obviousmy childhood, university years, career as an active scientist and professor, and my first years as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

As this book's broad features came to cohere, I began to see Avoid Boring People as an object lesson, if not quite an exemplary history of the making of a scientist. It is my advice in the form of recollections of manners I deployed to navigate the worlds of science and of academia. The thought that this instructive value might be made explicit in the form of self-help led me to conclude each chapter with a set of remembered lessonsrules of conduct that in retrospect figured decisively in turning so many of my childhood dreams into reality. Suffice it to say, this is a book for those on their way up, as well as for those on the top who do not want their leadership years to be an assemblage of opportunities gone astray.

Skipping high school's last years led to my never learning how to type, and even today I generate left-hand-written versions of the first drafts of all my writings. Without my administrative assistant Maureen Berejka's ever-increasing skill in handling strings of seemingly indecipherable squiggles, this book could never have come into existence. In preparing successive early drafts of the manuscript, I much benefited from the able Barnard College chemistry graduate, Kiryn Haslinger, whose expert knowledge of the English language led to many improvements in my word use. New York University psychology graduate Marisa Macari ably provided help in inserting period photographs and documents. Later, Stanford biology major Agnieszka Milczarek invaluably corrected the many errors of fact and spelling spotted by friends to whom I sent preliminary drafts. Finally, I much thank George Andreou of Knopf for masterly editing that has much improved this volume's clarity and intellectual thrust.

Jim Watson, March 26, 2007