1. Early Childhood in Minnesota

Just after dawn on December 29, 1890, a mounted force of 500 soldiers of the U.S. 7th Cavalry, led by Colonel James Forsyth, rode into an encampment of Indians led by the Miniconjou chief, Big Foot, at Wounded Knee Creek. The army had intercepted the small band of Miniconjou five days earlier 30 miles east of the Pine Ridge reservation, where they had hoped to rendezvous with Short Bull, Kicking Bear and their followers at a remote outcropping of steep rock called the Stronghold. The tribes were moving in protest of the ongoing mistreatment of their people at the reservations.

Two weeks earlier the Lakota holy man, Sitting Bull, and seven of his warriors had been gunned down by Indian police in his home at the Standing Rock reservation. Six of the police officers were also killed in the violence, and the incident left the nearby native population in a fury. The slain tribal leader was well respected and was among those who helped band their tribes together in recent years to ward off the incursion of federal troops and white settlers on their lands. One of the heroes of the decisive Indian victory over Lt. Colonel George Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, Sitting Bull and his followers had been pursued by U.S. forces and fled over the Canadian border, where they remained until 1881. At that time, abandoned by the Canadian government and suffering from the harsh Canadian winters, Sitting Bull had brought his people back to the reservation on U.S. soil and surrendered. Later he had found fame and some fortune touring with Buffalo Bill Codys Wild West Show in 1885 but quit after months on tour with the show, returning to his home at the Standing Rock reservation, where he redistributed most of the money hed earned among his people.

In the aftermath of Sitting Bulls death Big Foot, Kicking Bear and Short Bull defiantly moved their tribes off their reservations. Along the journey Big Foot had contracted pneumonia and was relegated to riding in the back of a wagon. The party slowed and was intercepted. They never made it to the Stronghold.

Forsyths mounted force was backed by four Hotchkiss cannons positioned on high ground surrounding the camp of 350 Indians, two-thirds of whom were women and children. The air was cold and crisp and the sky was a steel gray as a heavy snow threatened to sweep in from the north. As so often happened in cases involving Indians and armed U.S. forces, who fired first was never really known, but the outcome had become all too familiar. Forsyth demanded the Indians surrender their weapons and return to the reservation peacefully. All but one, a deaf man named Black Coyote, did so quietly. When an officer tried to take his gun, Black Coyote resisted and the gun went off. In an instant the tense but peaceful confrontation erupted in hand to hand combat. Outnumbered three to one by their would-be captors, the Indians began to run for cover. The Hotchkiss guns were unleashed on the fleeing Indians, strafing them with a hail of cannon and gunfire. Less than an hour later, 200 members of the tribes, mainly women and children and the elderly, lay dead or wounded in the cold winter air. Big Foot had been among the first to fall. Army casualties listed as 25 killed and 39 wounded. Public sentiment for the plight of the Indians swelled in light of the massacre. Forsyth was later tried for murder in the incident but was exonerated.

In the days and months that followed, as the echo of the big guns and the emotive cries of innocents fell silent on the northern plains, winter turned to spring and spring into summer. On August 19, 1891, 600 miles east in a town called Dodge Center, Minnesota, Milton La Salle Humason was born.

In perhaps a strange coincidence of fate, on that same day the 67-year-old spectroscopist, Sir William Huggins, opened the proceedings of the conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Cardiff, Wales. James Keeler, who had resigned as director of the Lick Observatory in June, referred to Huggins in a note to his successor, William Campbell, as the founder of the science of astronomical spectroscopy. Of the early spectroscopists, Huggins had done more than perhaps anyone else to advance the emerging field of astrophysics. He had been the first to observe the emission lines in the spectra of nebulae, to use the Doppler principle to determine stellar motion along the line of sight and identify the ultraviolet lines in the spectra of hydrogen on film. All of these practices, Milton Humason would one day put to good use in helping to advance the field even farther.

In his speech to the B.A.A.S. Huggins, who, along with his wife Margaret was far from finished in contributing to the advancement of the field, discussed the existing and emerging developments of the moment, with a nod to the spirited group of young men who would continue the research on stellar evolution into the future. Happy is the lot of those who are still on the eastern side of lifes meridian, the newly elected president said in closing. His comments were directed largely at young George Hale, who was seated in the audience that night and was set to give a presentation of his attempts to photograph solar prominences the following day. The two had met a week earlier at the Huggins observatory in the Tulse Hill district of London, and Hale had delighted his older counterpart with his energy and enthusiasm, both for the field of astrophysics and for Huggins contributions to it.

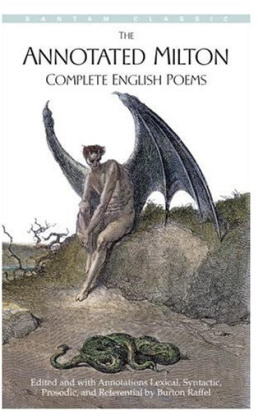

The massacre at Wounded Knee and the B.A.A.S. conference in Wales illustrate the extraordinarily dichotomous times in the United States into which Milton Humason was borna new world brimming with opportunity and industrialization straddling an antiquated yet prideful world, banished ignominiously to the margins of society. In his eight decades Humason would live through the greatest period of modernization in history, one that began with the advent of the telephone and the lightbulb and ended with men walking on the Moon. And although he always greeted the world he lived in with a handshake, a smile, and a story or a joke, his love for that antiquated world never waned (Fig. ).

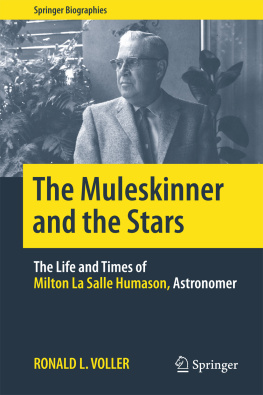

Fig. 1.1

A portrait of Milton Humason, circa 1894

Humasons ordinary birth came during an extraordinary period in the growth of the United States as a nation. With the nomadic tribes of the northern and southern plains now contained on reservations, European emigrants were freer than ever to push west in the quest for land and opportunity. Western expansion, the discovery of oil and gold, and advances in building technologies were creating unprecedented wealth. The steam engine had become the workhorse of the surging Industrial Revolution while telephones, electricity and the lightbulb were enhancing both work and living environments. Victorian Era charm and grace were being replaced by the grimy advance of industry both in Europe and at home in America.