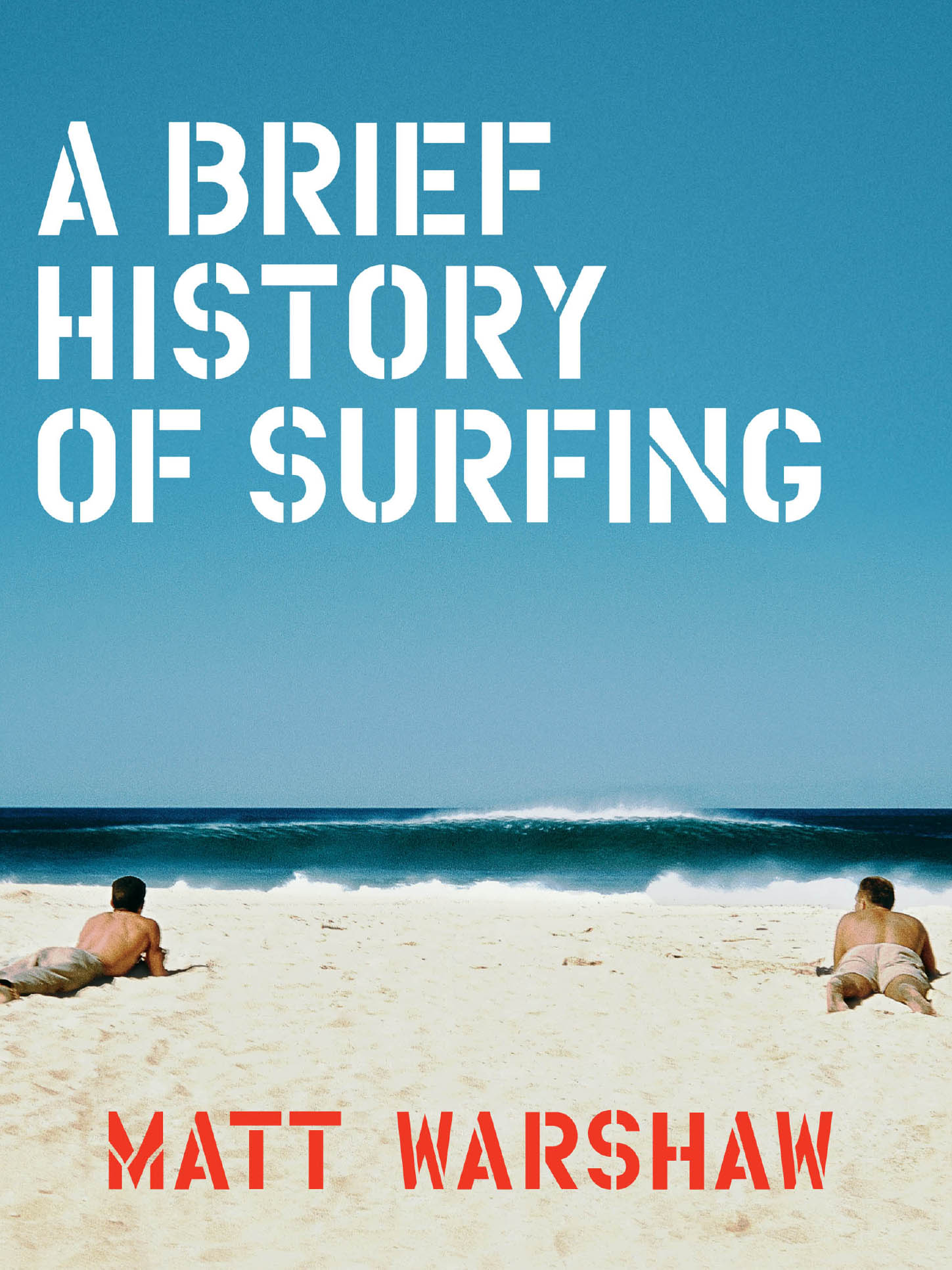

Text copyright 2017 by Matt Warshaw.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-5194-6 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4521-5280-6 (epub, mobi)

Designed by Ben Kither

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

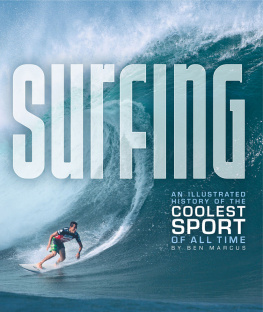

front cover:

Pat Curren and John Elwell, Yokohama Bay, Hawaii, 1959.

Photo by John Severson.

back cover:

Eddie Aikau.

Photo by Dan Merkel/A-Frame.

: Sam Hawk.

: Dusty Payne.

: Corky Carroll.

: Tom Blake and Santa Monica lifeguards.

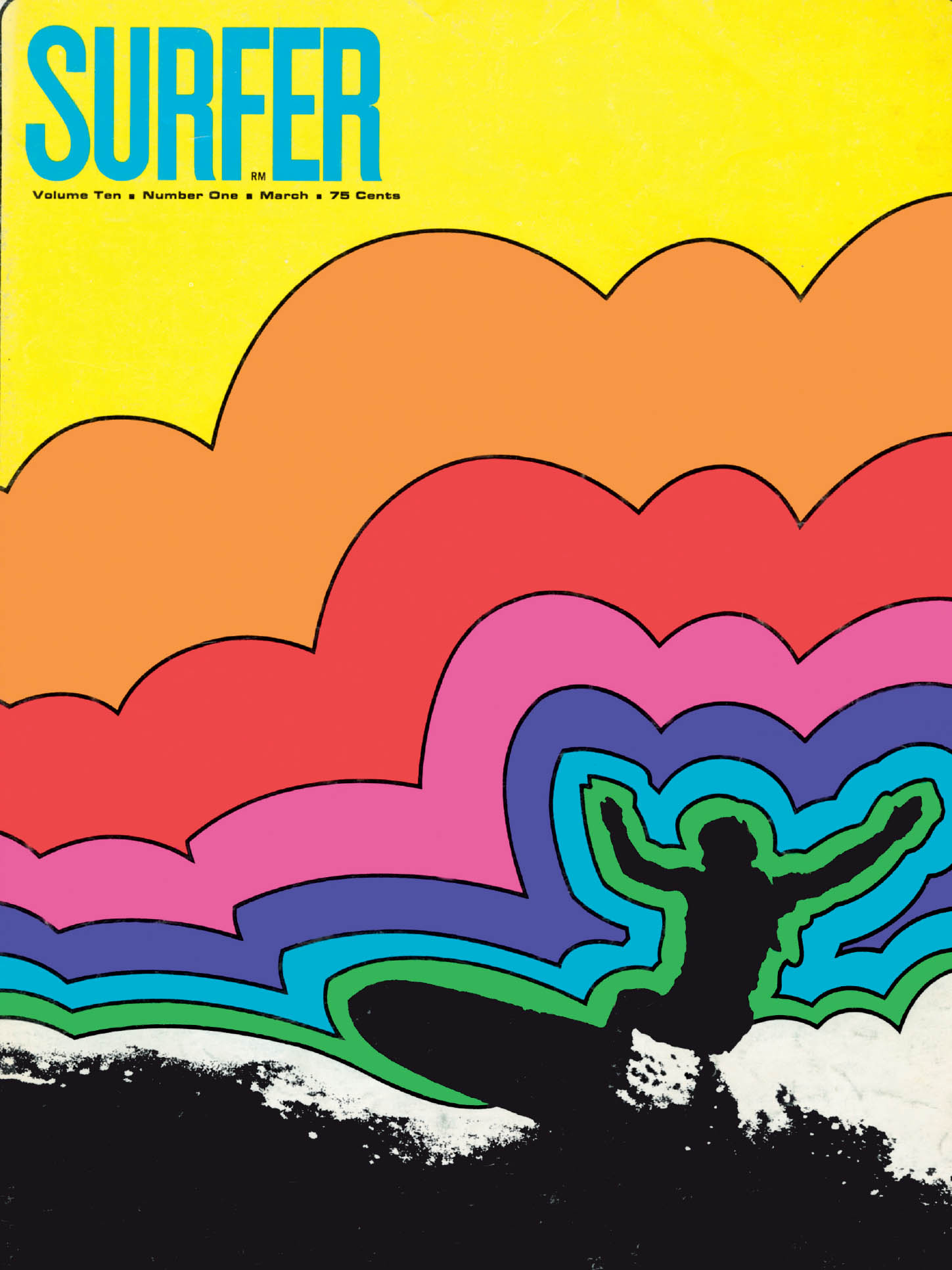

: Detail from 1968 Surfer magazine cover.

: Palos Verdes Cove.

: Hobie Surfboards shop.

: Midget Farrelly.

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

Introduction

By Matt Warshaw

The original History of Surfing was my attempt to clean-and-jerk the entire gorgeous, sprawling mess of a sport, to hoist it up where surfers and nonsurfers alike could see it anew and in full. I hoped to add verity to the record. For instance, remember those beautifully lacquered, solid-wood, Depression-era surfboards? For decades, received wisdom was that they weighed a knee-buckling 100 pounds. Pick up a hundred pounds of anything and walk from one end of the block to the other. Now imagine doing the same thing before and after every surf session. Equipment that heavy might not have killed the sport outright, but it would have dragged it down considerably. As it turns out, the average board made in the 1930s weighed about 50 pounds. Does it change anything, or lessen the sports achievements, to deflate little surf-world myths like this? Maybe, a little, but its the truth. And even sofifty pounds is still pretty damn heavy.

Demythologizing the sport, in fact, was another goal of mine. I couldnt wait to sledge away at the cheerleading and boosterism and perjured nobility layered onto most works of surf history. Pulling down shoddy historiographic handicraft feels good, just for its own sake. But the real purposeand the real pleasurecomes from the fact that the mortal, ground-level version of events is, almost without exception, more compelling than the legend or the myth. Surfing history has time and again been presented for two reasons: to convince nonsurfers that riding waves is an honest-to-goodness sport, rather than a beachfront novelty, and to reassure surfers themselves that their days and years spent chasing down swells is not only justified but virtuousthat their chosen recreation is in fact more of a calling. The rest of the world now thinks surfing is great. Fine. No harm there. The second part, though, has done the sport a disservice. Lets revel in surfings grace and beauty, and applaud the surfers bravery, innovation, and humor. Absolutely. But lets also acknowledge the sexism, the pettiness, the hubris, and all the other messy human qualities that are stitched and glued into the sports fabric. Leave room for second thoughts. One of my favorite quotes about the surfing life comes from Hawaiis Ken Bradshaw. Invariably portrayed as a brash, disciplined surf-warriorand celebrated in the late 1990s as the man whod ridden the biggest wave in the sports history up to that pointBradshaw mused late in his career about all the opportunities I missed because Im so obsessively addicted to surfing. He then added: Dont be me. I dont have what most human beings want.

Not for a moment do I think that Bradshaw, if given the chance, would really change his life or career. His ride has been long and thrilling and steeped in glory. Only when he reckons the cost of his all-encompassing pursuit, though, does he become a three-dimensional human being, rather than a two-dimensional stock character. Whats true for Bradshaw is true for the sport. Surf history is better when its not moonlighting as surf advocacy. Surfing is more clearly seen, and more authentically honorable, when it steps off its pedestal.

I turned in a final draft for the original History of Surfing in mid-2009, after four years of research and writing. Throughout, I was half-waiting for a surf-world epiphany or two to land on me. It never happened. But my biases and preferences all came through intact. Today, the mechanics of surfboard design, and all the attendant hydrodynamics, still bore me just as much as the forces behind design changethe rivalries, the spark of an idea, trial and error, dumb luckstill fascinate me. Its the same with surf competition. While I consider 90-some percent of surf contests to be silly distractions, the best events and the top competitors can distill a moment in the sport like nothing else. Nat Youngs amazing performance in the 1966 World Championships in San Diego was like hearing the thunder from the coming shortboard revolution almost a full year before it came into view. In the end, board design and competition both receive prominent roles in this history because, as often as not, theyre the quickest, most efficient route to the sports most interesting places.

What really attracts me, though, is tracing and understanding the jagged fault line between surf culture and culture at large. Its running down simple things like the etymology of dude, as well as following longer, episodic storylines: how Kathy Gidget Kohner went from an unknown fifteen-year-old Malibu mascot to the subject of a hit movie, which in turn put an entire generation of new surfers in the watermost of whom decided to hate Gidget as a surf-Eden destroyer, until they later came to love the film as a memento of their beachgoing youth. Almost every inch in this particular acre of surf history is deliciously fraught with morality plays, from the small and personalMalibu antihero Mickey Dora selling out to the Beach Blanket Bingo franchise, for exampleto the socially charged, like the pro surfing tours decision to hold contests in apartheid-era South Africa.

The nonsurfing world has shaped and formed the sport more deeply than surfers care to admit. Surf culture, in turn, has traveled and settled over mountains, plains, and cities, from coast to coast, nation to nation. For me, watching these two forces react to each other never gets dull: the circling and grinding and ignoring and ridiculingand, these days, more often than not, collaborating.

Next page