CONTENTS

Part One: Ancient History 19001950

Tyler Wright

The concept is not new. From the time the first waves were ridden, the ancient Polynesians were probably arguing about who did it better. Indeed, we know that before the missionaries intervened, the Hawaiians were wagering their boards, canoes, houses, and even the odd wife, on the contentious and highly subjective notion of who surfed better or best.

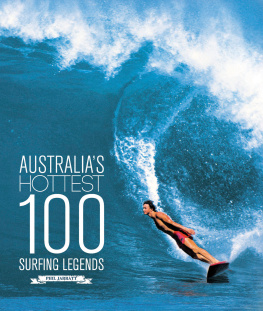

Venture into the blogosphere any day of the week and you will find new posts in support of the view that an unknown surfer on a little-known beac somewhere, anywhere, is infinitely better than, say, Kelly Slater. So lets get this out there up front: this book is not about that. In any case, in my humble opinion, there is no argument that Kelly Slater is the greatest surfer of all timethough you might get some argument about the greatest Australian surfers of all time. Layne Beachley and Mark Richards are the winningest, but is that necessarily the only criterion against which surfers should be judged?

This collection of profiles takes the broader view that contributions to the sport, culture and lifestyle of surfing come in many forms, so a sprinkling of precontest pioneers, surfboard builders, industrialists, eco-warriors, soul surfers and observers are included alongside Australias champions down the ages. It should also be noted that where a competitive record is used as the measure for inclusion, achievements must be seen in their historical context. Claude West, for example, won the first Australian surfboard contest by being first across the line, rather than for the quality of his off-the-lips or gouges, which were probably infrequent on his Duke-style hundred-pound redwood. And Snow McAlister, great surfer though he was, won most of his Australian titles by standing on his head, which does not rack up many points these days.

I am fully aware that none of the above is going to get me out of the firing line. Many years ago, I was a member of a panel that selected the fifty greatest Australian sportsmen of all time for inclusion in a book sponsored by Channel Nines Wide World of Sports program. Although the selection was a democratic process, sportscaster Mike Gibson never got over the fact that he got outvoted over tennis champion Ken Rosewall, an anomaly (in his view) that after publication he brought up at every opportunity.

I have no Mike Gibson this time around. Australias Hottest 100 Surfing Legends is all my own work, informed by almost half a century of close involvement with surfing as a commentator, surf industry professional and lifelong surfer, and, more recently, as a keen student of our early surfing history. But that does not mean that my hottest 100 is the same as yours. It doesnt even mean that my selections would be the same this time next year. Take the current state of womens professional surfing, for example. As I write there are half a dozen brilliant young Australian women surfers within striking distance of a world title, and not all of them are in this book.

Even in casting my eye over the final selection for previous decades, I see omissions that I really didnt plan, but who do you take out to make the space? For these reasons I ask you, the reader, to view this book as a window into our rich surfing history, rather than as a definitive judgement on who is or is not historically noteworthy.

Of this, however, I am certain: everyone on my list, whether their contribution was long ago or is happening right now, is enriching our sport and inspiring us all to surf more, if not better.

Phil Jarra / Noosa Heads / October 2011

Australia was surprisingly coy about using its beaches for leisure at the start of the last century. In fact, ocean bathing in daylight hours was technically ille gal, courtesy of a series of colonial laws put in place in 1833. Although these archaic laws were not always enforced, surf swimming was generally discouraged as dangerous and dclass. The real deal at the beach was to dress to the nines and swagger along the boardwalk with a fashionably corseted babe.

While policing the daylight bathing bans increasingly seemed to be a lot of hard work for no common good, it took a media campaign to actually instigate a change of law. At the start of summer 190203, Manly newspaper editor William Gocher promoted a public protest against the daylight ban, and at high noon on the first Sunday of the season he led the way into the surf at Manly. The police watched and did nothing as Gocher and friends emerged from the waves, even after the journalist pleaded to be made an example ofhis photographer was waiting with a box brownie to capture the moment of arrest. In a matter of weeks, the bathing laws had been repealed.

But while the new freedom to swim in the sea, albeit in neck-to-knee woollens, brought prosperity to beachside towns, there was also an immediate downside. Seventeen people drowned while swimming in the surf at Manly in 190203 alone, prompting a local fishing family, the Slys, to launch their dory each weekend and unofficially patrol the line of breakers. All the popular Sydney beaches had the same problem, but Bondi, soon to become Australias beach culture capital, was the first to respond, establishing the Bondi Surf Bathers Life Saving Club in 1907. The concept of volunteers patrolling surf beaches soon spread around Australia and the world, and, for the next half-century, most young Australians who aspired to ride the waves learned to do so through a strictly regimented process that put work before play.

The surf lifesaving movement did introduce competitive surfboard riding events after World War I, albeit in the form of paddling races. Bodysurfing, introduced by Pacific islanders in the 1880s and 1890s, remained the dominant surf sport, but boardriding, first tried in Australia in the early 1900s and popularised by the visit of Duke Kahanamoku in 191415, started to gain a following, particularly among youthful thrillseekers.

In California and Hawaii lifeguarding and surfing evolved side by side, but in Australia a cultural gap developed between those who felt the call of the waves and those who answered the call to duty; there are remnants of it even today. While many Australian surfing pioneers came through the surf lifesaving movement, their real place in history came when they rebelled against it.

A t the dawn of the twentieth century, although the great majority of Australians lived by the coast, they were oblivious to the leisure opportunities the beach offered. Its somewhat ironic that a nation founded on convict labour came to realise one of its own natural treasures through a people much more recently deprived of their home and their freedom.

New Hebridean Tommy Tanna (probably named for the island of his birth) was one of the many victims of blackbirding, a late-nineteenth-century practice of recruiting Pacific islander people as labourers, often by force or kidnapping, an enterprise for which there were many apologists among the rising Australian middle class. Working as a gardener for the wealthy Williams family in Sydneys northern beach suburb of Manly in the late 1880s, Tommy took to bodysurfing the rolling waves as he had done since early childhood at his island home. The children of his employer (one of whom was a young lad named Freddie), and their friends, and their friends friends, watched in awe as the athletic young islander rode wave after wave for more than 50 metres. Soon the more adventurous of them were joining in, despite the fact that ocean bathing was banned.

Next page