CONTENTS

I first glimpsed the surf dream on a Sunday afternoon in East London. It was the fag end of the seventies and I was nursing a broken wrist and a badly sprained ankle sustained while skateboarding the hill outside the family house. I was feeling bored and sorry for myself. Rummaging though an old pile of magazines in my uncles bedside cabinet, I found a stack of old Aussie surf mags amid the dog-eared copies of Playboy and Motorsport Magazine. Despite the raging hormones of this moody thirteen-year-old, it was images of surfers riding the curvatures of tropical waves that burned into my cortex, far deeper than those of the honey-hued bunnies and classic Ferraris. The surf magazines evoked a world so exotic, so perfect, so beautiful and so essentially other to my suburban existence that I was instantly intoxicated. From that moment I was determined one day to become a surfer.

Fast forward five years. Im paddling out at dawn for the first time on a battered old board at Noosa Heads in Queensland, my stomach a nest of butterflies. Having failed to realise that it was possible to surf around the shores of England, I had spent two years of my teenage life toiling on building sites in London, working to save the money for a plane ticket to Australia. I eventually scored the airfare, flew in to Brisbane, bought a crappy old Mazda Bongo campervan, stuck in my well-worn Best of the Beach Boys tape and headed north.

A lot of water has passed under the keel since I caught that first wave at Noosa. Back then, in the mid-eighties, surfing was still very much a marginal coastal creed outside of Australia, California and Hawaii. In places such as Britain, Japan, South America and most of Europe it was practised resolutely under the radar by a small cadre of passionately committed pioneers. In the two decades since, surfing has become a billion-dollar industry that has penetrated ever deeper into the mainstream. Engaging with skate cultures thrash-and-burn ethos at the end of the eighties, the industry absorbed the global dollar generated by the explosion of snowboarding in the nineties. Surfing now lies at the heart of a truly global action sports industry whose wealth and influence would have been unimaginable to preceding generations. In the process wave-riding has become one of the central elements in the lives of millions around the world, giving access to the kind of sustained euphoria that no other activity can bring. Not everybody has an ocean on their doorstep, but everybodys gone surfing.

Ever since its rebirth in late-nineteenth-century Hawaii, surfing has transformed the lives of the people it has touched. It has galvanised countless relationships in shared experience and lent purpose and piquancy to innumerable wandering adventures and inner explorations. Reflecting both technological and aesthetic trends, it has inspired musicians, photographers and artists to produce some of the most dynamic work of the last forty years. Many of the masters of the sport have proved themselves athletic giants, creative visionaries and cultural heroes although their stories are largely lost to the narrative of popular culture. Surfing is rich in anthropological, historical and cultural resonance and is full of metaphoric potency. As well as being sun-kissed exponents of the rock-and-roll dream that gobbled up a planet, surfers are initiates of an intensely physical set of rituals and practices that can produce a state of pure, natural joy. And surfers have invented a word for that very specific type of joy: stoke.

Its this incredibly rich, diverse nature that The Book of Surfing attempts to express. Structured so that you can dip in and out, as well as reading it through from first page to last, the book builds up a multi-layered picture of wave-riding and the culture that it has created. It aims to entertain the old salts as well as to inform and inspire the newly surf stoked. Its nave to think that any medium could adequately express the light and shade of a life that revolves around a wave. If a few readers of this book are motivated to make it their goal to find out for themselves whats so special about this surfing life, then my mission will have been accomplished.

Michael Fordham

Over the last century, the search for the perfect wave has shaped surf culture. Always an elusive notion, it has been constantly re-defined.

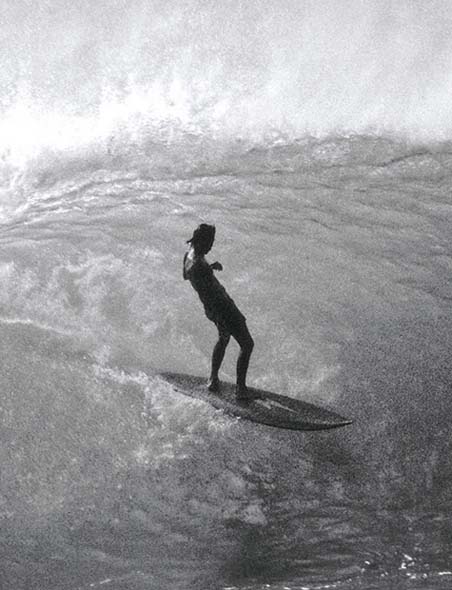

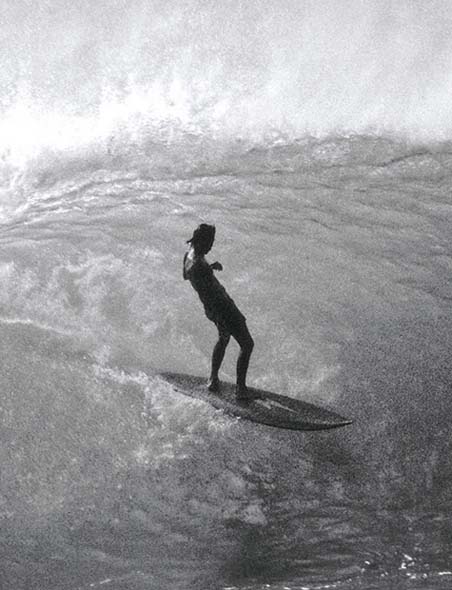

Picture the scene at Waikiki, Oahu, around 1912. The tourists started arriving a few years ago, drawn by the hibiscus-heavy Hawaiiana propagated by writers such as Jack London. The small coterie of local beach boys, heirs to the grand old indigenous Hawaiian tradition of wave-riding, are making a living teaching the rich haoles to swim and to surf. The long finless boards, hewn from heavy timber, are well suited to the angles and trajectories of Waikikis waves. The boys who ride them are the first proponents of the surfing lifestyle, and Waikiki becomes the earliest epitome of a waves manifest perfection.

Cut to Palos Verdes Cove, California, some time in the mid-1930s. On the beach, the members of the Palos Verdes Surf Club are doing their best to replicate the Hawaiian lifestyle that had been introduced to the mainland by the likes of visiting Hawaiians Duke Kahanamoku and George Freeth. Theyre catching lobster and abalone. Theyre strumming ukuleles and drinking wine out of jugs around an open fire. Meanwhile, Tom Blake, visionary waterman, is paddling way outside of the peak on a big day. His hollow cigar-box board, fitted now with a single fin, is more manoeuvrable than anything seen before. The relatively light board, with its stabilising skeg, enables Blake to draw tight turns and acute angles down the faces of the Coves big, fast-moving walls. This is Californias pre-war halcyon of unspoilt shorelines and rich inland forests, hills and pastures. Out beyond the beach, surf perfection is realised.

Come to Malibu in 1958. Surfers are riding First Points long, peeling waves in the dynamic style known as hotdogging. Dewey Weber and Mickey Muoz are at the cutting edge of the hotdog revolution. Theres a crowd on the beach willing to be impressed by the new and the strange. The foam and fibreglass boards the heroes ride are increasingly light and dynamic. Theres a rock-and-roll soundtrack to the parties on the beach, and the rides along the Bus seemingly endless, gently tapered walls are just waiting to be filled with the new stylistic vernacular. Malibu is the canvas upon which modern surf style was painted.

Smell that patchouli oil? Yes, its 1973 and we find ourselves at Uluwatu in a little-known island outpost called Bali. The left-breaking, fiercely pitching maw thats firing with razor-like sharpness down the southwestern tip of the Bukit Peninsular is at the edge of surf cultures consciousness. With short, spear-like boards a tuned-out core of a globally wandering surf tribe is exploring the limits of speed and hollowness. Waves of undreamt steepness and ferocity that would have sent Blake scampering back to the beach are being harnessed by the likes of Terry Fitzgerald, Gerry Lopez and Michael Peterson. The surf magazines back in California and on Australias east coast have spread the dream of tapping into the power source no matter how impossible it might have seemed only a few years previously, and Uluwatu is the ideal aspiration for the children of the shortboard revolution.

Next page