FOR MY MOTHER

CONTENTS

IN OTHER WORDS, THE HIGH AND THE LOW,

THE HISTORIC AND THE MODERN, WERE BUILT

ON THE BANKS OF THE SAME RIVER.

Peter Carey, Wrong About Japan

AUTHORS APOLOGY

AS A HISTORY of surfing, this book isnt definitive. It completely shortchangesamong other major forcesDale Velzy, Mary Ann Hawkins, Greg Noll, and most of Australia. What Ive tried to assemble is a folk history of surfing, a personal sketch for any curious reader of how the modern sport moved around the world and mingled with cultures that either have nothing to do with Hawaii or have strong reasons to resist pop silliness from the first world. The result is a story of hippies, soldiers, nutcases, and colonialism, a checkered history of the spread of Western culture in the years after World War II.

Dude, you should have gone to Brazil, people told me. Or, Are there really good waves in Gaza?as if the point were to search for beautiful surf. No, no, no. I left out major wave-riding nations like Mexico, France, and South Africa because most surfers know about them. Wherever possible I chose offbeat nearby countries (Cuba, Germany, So Tom and Prncipe) to give the general reader an idea of how surfing reached each general part of the world and still, I hope, offer the dedicated surf historian something newabout how the sport mingled with Communism, or how it wound up in the North Sea.

The travelspread over several yearsstarts with Chapter land-locked scribbler, living as a journalist in Berlin. But Id never stopped being a surfer, and Id lived too long thinking the material I grew up with, the relentless superficial glare of southern California, had no value for a writer. Even pop culture has a human history, and modern surfing happens to be as American as baseball or jazz. By that I dont mean to claim it for Americasurfing, almost as much as soccer, is a world sportbut I do want to provide ammunition against the eternal domestic bigots who say certain (ever-shifting, normally coastal) parts of America somehow dont belong; or against Europeans who think everything exported by America is bad; or against Northeastern snobs who think surfing isnt worth their time. Those three groups of people would never care to be caught together at a dinner party, but to me theyre partners in ignorance.

Anyway, this isnt Endless Summer. Its not a pleasure trip, or a search for the ultimate stoke. When a surfer takes off on a wave, there are two possible results, and my book is about them both.

1

CALIFORNIA AND HAWAII:

AS CIVILIZATION ADVANCES

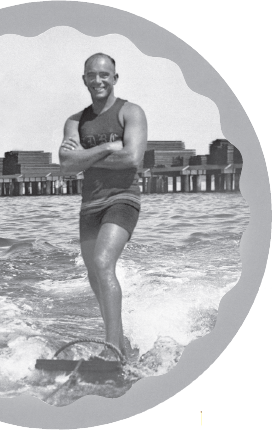

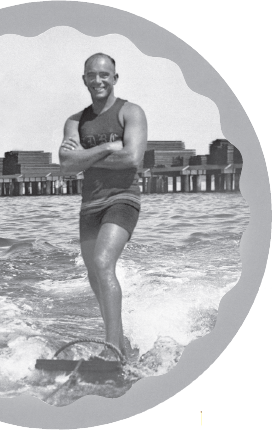

George Freeth aquaplaning, c. 1915

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, the George Freeth memorial in Redondo Beach, California, was a saltbitten bust of a lifeguard who gazed with the stoicism youd expect from an early surf hero into the deep mysteries of a concrete parking garage. His back was to the Redondo Pier. Most locals jogged or skated past the sculpture without examining the plaque, which read, disingenuously, FIRST SURFER IN THE UNITED STATES, then related the story of how Freeth was paid by the Los Angeles real estate and streetcar magnate Henry Huntington in 1907 to lure people to ride the Red Line tram to Redondo Beach on sunny afternoons and watch a new kind of athlete trim the waves. George Freeth was advertised as The Man Who Can Walk On Water, according to the plaque. Thousands of people came here on the big red cars to watch this astounding feat. George would mount his big 8-foot-long, solid wood, 200-pound surfboard far out in the surf. He would wait for a suitable wave, catch it, and to the amazement of all, ride onto the beach while standing upright.

Redondo Beach was, and still is, a glamour-resistant Los Angeles suburb. In the early 80s the beach was drab and blighted with rusting Coppertone trash cans and piles of seaweed. So I wondered why it would have occurred to people in 1907 to come here and watch a man do something so normal: ride onto the beach while standing upright. Big deal. Could he do aerials? The surfers I saw in magazinesMartin Potter, Mark Occhilupo, Shaun Tomsoncould all do aerials.

At the time I was a new and not very good surfer who walked to the beach some mornings before school with a lanky mathematician named Tim who had a dark sense of humor and an oversized Adams apple. Tim, with his brilliant technical mind and his nerdy leather briefcase, didnt feel welcome at Mira Costa High. He tested out before graduation, I think during his junior year. Other kids who surfed, the California punks and spoiled rich sons of industry, floated in the lineup in expensive, colorful wetsuits and set a tone of cool neither of us could match. But Tim wanted to surf in contests. He pushed himself in the water the way he pushed himself in class, and under his influence I learned to appreciate the magisterial command of pros like Tom Curren and Mark Foo; the aggro wave-whacking styles of Occhilupo and Brad Gerlach; and the clever innovations of guys like Cheyne Horan, who won surf titles on boards hed invented himself.

By then surfing was too far along for me to imagine any individual as the first surfer in America. Surfing was too obvious. It was an ancient sport in Hawaii; how come it took until 1907 to reach America? Didnt native Californiansthe Chumash, the Ohlonesurf? (Actually, no.) But my teenage skepticism was justified. Freeth was only the first celebrity surfer in California. The first men on record to surf North America were three Hawaiian princes who noticed that waves at the San Lorenzo River mouth in Santa Cruz were up to snuff. In the late nineteenth century, Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole, heir to the Hawaiian throne, and his brothers David and Edward attended a military school in San Mateo, over the hill from Santa Cruz. They shaped their own boards from local redwoods and hauled them out to the beach one day in 1885 for a little fun. The young Hawaiian princes were in the water, wrote a local paper, enjoying it hugely and giving interesting exhibitions of surfboard swimming as practiced in their native islands.

Theres also the story from Richard Henry Danas Two Years Before the Mast about Hawaiian crewmen from a ship called the Ayacucho, which met Danas ship near Santa Barbara in 1835. It was Danas first California landing. A rowboat full of his shipmates was waiting in high evening surf for a chance to row in when a launch from the Ayacucho came alongside of us, with a crew of dusky Sandwich-Islanders, talking and hallooing in their outlandish tongue. They knew that we were novices in this kind of boating, so they showed the haoles how it was done. The Hawaiians had had outrigger practice, and outriggers are close ancestors of surfboards. Dana then sets down the earliest English description of riding California surf. We pulled strongly in, and as soon as we felt that the sea had got hold of us, and was carrying us in with the speed of a race-horse, we threw the oars as far from the boat as we could, imitating the Hawaiians, and took hold of the gunwales, ready to spring out and seize her when she struck, the officer using his utmost strength, with his steering-oar, to keep her stern out. We were shot up upon the beach, and seizing the boat, ran her up high and dry, and, picking up our oars, stood by her, ready for the captain to come down.

Next page