To Kirsten,

for sharing the ride

and

in honour of Duke Kahanamoku,

who pushed us all into our first wave.

There is a wisdom in the wave

DORIAN DOC PASKOWITZ

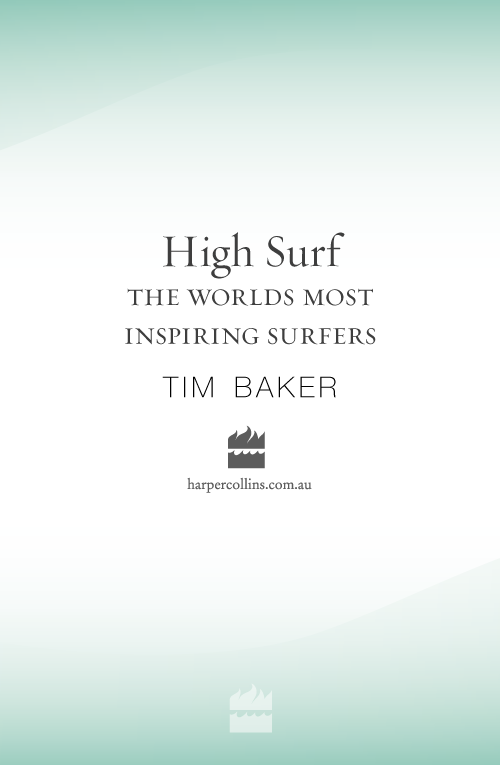

The central question posed throughout this collection of surfing profiles, anecdotes and quotes is: What have I learnt from surfing? If I were to ask myself that question, the short answer is a lot. But that hasnt always been the case.

Like the undulations of a wave itself, it has varied; at some stages in life the answer has been, everything, and at others, very little. However, this question has been at the core of almost every surf story Ive ever written over many, many years, seventeen of which make up my 2006 published collection Wind on the Water. There are 40,000 words in that book; a figure which would seem to indicate (as do the reflections here in High Surf) that theres more to surfing than surfing, and that the question about what has been learnt is quite profound!

From the moment you become aware of undulatory vibrations and wave energy, whether through surfing, awareness of the ocean, or repeated, detached observations of life around you, strange understandings enter the realm of your consciousness. The wash of words such as ebb and flow, rise and fall, high times and low times, night and day, rich and poor, male and female, black and white, yin and yang, life and death, and so on, come to assume some special significance.

These are things you have to discover in your own way, alone, and in your own time. As far as surfing itself is concerned, not one of them has anything to do with media and surf industry clichs.

The line of our lives may appear to be straight, from a drop of semen and a tiny egg, to a pile of ashes, but in reality we are forever rising and falling, riding waves. One of them is something we call time, and which we measure in seconds, minutes, hours, days, years, and so on.

What we perceive as a linear phenomenon is in fact a circulatory one, and something that is beyond measurement. Our little world is actually part of a wave that is endlessly circulating up and down, over and around, cycling and recycling this way and that way. Sometimes it feels the bottom and feathers or breaks on a sandbar or reef in the form of a setback or a hiccup in our lives. It then re-forms to roll on and on, its energy emanating from who knows where?

This is the wave that is closest to us, its the one we call life, and sometimes think we understand. But in fact it is only a component part of a bigger wave, which in turn carries us onto other waves beyond our comprehension, reaching out forever into the cosmos.

At the end of our lives we pull off our little wave, and stand utterly alone, staring into infinity. Thats where our ultimate wave stands waiting to be ridden, and its not a tow-in, it has to be paddled into alone and unaided!

Thats one of the things Ive learnt from surfing, along with being free. The two are in fact part of the same wave. The challenge at my age is to stay with it. In fact the challenge of every age is to stay with it!

As the reflections here in High Surf make abundantly clear, that is exactly what millions of surfers are doing every dayhanging in there! Its what weve always done.

The publication of this book is a long overdue recognition of another piece in the complex jigsaw of just what surfing is, and what it means to be a surfer. The fact that writers like Tim Baker and others are now addressing questions such as What have I learnt from surfing? is a cause for optimism. It means that so long as the earth has oceans, the indefinable wave of nature that is surfing will continue to roll, and somewhere, somebody will be riding it!

JACK FINLAY, WRITER, SURFER

Introduction

{ why surfing? why now? }

Surfers are the throw-aheads of mankind, not the dregs; they arent the black sheep of humanity, but the futurists and they are leading the way to where man ultimately wants to be. The act of the ride is the epitome of be here now, and the tube ride is the most acute form of that. Which is: your future is right ahead of you, the past is exploding behind you, your wake is disappearing, your footprints are washed from the sand. Its a non-productive, non-depletive act thats done purely for the value of the dance itself. And that is the destiny of manIts perfectly logical to me that surfing is the spiritual aesthetic style of the liberated self and thats the model for the future.

TIMOTHY LEARY, SURFER MAGAZINE,

JANUARY 1978

In a boardroom in Bangkok, several hundred miles from the nearest surf beach, big wave rider Ross Clarke-Jones lectures a group of advertising industry directors. Their conference is titled The Year of Living Dangerously, and Ross is their impeccably qualified guest speaker. His topic: risk taking, trusting instincts, jumping through windows of opportunitythe tenets of surfing huge waves neatly mirroring the latest business school doctrine.

In New York, eminent scientist and biotechnician Vezen Wu, after discovering a new form of antibiotic in carnivorous plants and developing cutting-edge medical software, has his world of computers, petri dishes and microscopes abruptly turned upside down when he discovers surfing. He finds himself thinking about waves all day long, doodling them in his notepads between dedicated surf sessions in New Yorks grey and chilly waters. So smitten is Wu by the sense of euphoria surfing gives him, he devises a new research projectrunning clinical trials using surfing to treat depression. Wu becomes convinced that the negative ions generated by breaking waves could provide a natural alternative to anti-depressant drugs.

In California, professional longboarder Israel Paskowitz, of the legendary Paskowitz surfing family, discovers that taking his young autistic son surfing dramatically helps his condition. Israel and his wife Danielle soon launch Surfers Healing, a charitable foundation dedicated to introducing autistic children to the calming powers of the waves.

In Indonesia, New Zealand born doctor Dave Jenkins takes time out for a surfing holiday in the remote Mentawai Islands. The oppressive health problems of the local people provokes an epiphany that sees Dr Dave throw in his well-paid medical career in Singapore, mortgage his house, and launch a humanitarian aid agency. Surf Aid International soon attracts the support of the world-wide surfing community, drastically reduces rampant malaria in the Mentawais, and comes to the aid of remote island communities devastated by the 2004 tsunami. In so doing, this tiny group of surfers earns the praise of the World Health Organization, the US Navy, the UN, and established aid agencies like AusAID and NZAID.

In south-west France, wealthy English industrialist Greville Mitchell takes his wife Lisa and surfing son for a seaside holiday, to coincide with the French leg of the pro-surfing tour. He wanders down the beach one afternoon in Lacanau and becomes entranced by the spectacle of pro surfers Luke Egan and Jeff Booth surfing a heat. So mesmerised is Greville by the surfers unearthly grace on the waves, he wades waist deep into the ocean to get a closer look. He returns to his familys holiday apartment wearing soaking trousers and a glazed expression. His wife Lisa claims he has never been the same. Greville soon diverts large chunks of his personal fortune into funding a full-time medical team on tour for the surfers, and propping up the sports cash-strapped world governing body. A chronic workaholic, Greville takes up longboarding and credits surfing with literally saving his life.