Frank Ryding - Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor

Here you can read online Frank Ryding - Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Pen & Sword Books, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

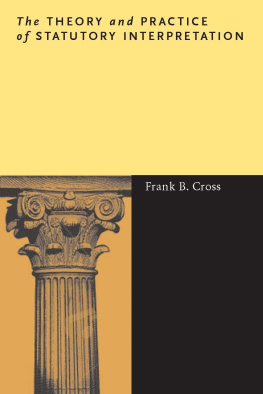

- Book:Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor

- Author:

- Publisher:Pen & Sword Books

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor

Better to Light a Candle

Frank Ryding

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Frank Ryding, 2017

ISBN 9781526716880

eISBN 9781526716903

Mobi ISBN 9781526716897

The right of Frank Ryding to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

This book is a true memoir of the 35 years of work by the author as a doctor for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the British Red Cross

I t was during one of the worst times, one of the seemingly hopeless times. As I was crouching for safety under an operating theatre table in a godforsaken part of Somalia, while shells exploded around us, I seriously questioned why I worked for an aid agency at all and what little use we were with violent death surrounding us. We were helping such a very small number of the victims here. My attention was illogically distracted from the gunfire outside to some graffiti written above an arched doorway in Somali script. A local nurse translated for me:

It is better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness.

It seemed to offer an explanation, some purpose to the years I spent before and after working with the International Red Cross in many of the most horrific wars on earth. Often it was the only motivation I had.

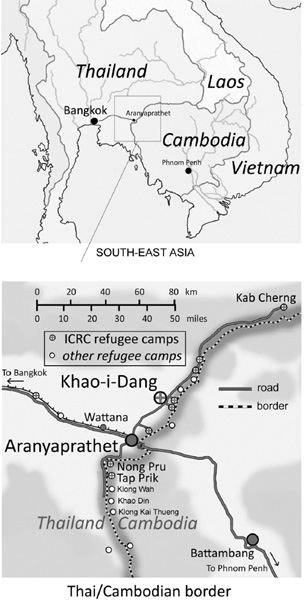

T he forest in Cambodia was noisy with exotic birdsong but the makeshift hospital in a clearing was quiet as always. Peaceful wasnt the right word: the atmosphere was subdued and wary. Already by noon I had seen more than fifty patients with malaria. Some were severely affected and I knew that two of them, despite treatment, would die before tomorrow morning. I hadnt expected that within the next hour I would see five people killed by shell and gun fire.

It could hardly be called a hospital. The wards were just four huge bamboo shelters open at the sides and covered with palm leaves for a roof. It had been built in an isolated part of western Cambodia by refugees fleeing from the chaotic and brutal fighting to the east but it was only 200 metres from the border with Thailand.

The air was hot and humid and I was so used to the incessant rasping of crickets that I hardly heard them now. The constant rhythm was suddenly broken by a deep, booming sound which I thought was thunder, but this was the wrong time of year. Everything stopped in the hospital as people listened; even the birds fell silent. The sound came again, and again. Was it getting closer? Out of the forest from the direction of a refugee village, people were running. Men with armfuls of AK-47 assault rifles were handing them out. Women were carrying babies or small children. Other older children followed them crying. The Cambodian nurse, Chantrea, who was helping me with the patients, pulled me out of the bamboo ward ...

Come with me. Its the Vietcong, she shouted. Theyre attacking the village. Theyre shelling it. Get to the bridge, get into Thailand.

What about the patients? I asked. Most of them were running with us but some, the very ill, were left behind.

Go. This is not safe for you, she said, as she pushed me towards the narrow bamboo bridge over a small ravine which marked the border with Thailand.

As I crossed the bridge with the three other members of the Red Cross team, I expected the Cambodians to follow, but a number of armed Khmer Rouge soldiers, the infamous communist fanatics who, it was said, had murdered over three million of their fellow Cambodians, stood like sentries preventing them from passing. There would be no deserters here. Everyone would have to turn and fight.

I heard shooting from the direction of the village, then distant machine-gun fire. We waited and after twenty minutes there was silence. It was an hour before the tension eased. We tentatively made our way back over the bridge and work was resumed.

Chantrea told me the attack had failed but there had been casualties. Many had been killed and they were bringing the wounded to the hospital. The first was a woman of maybe 25 who had been hit in the chest by shell fragments. It was hard to see the blood which had soaked her black shirt but a tear in the fabric showed where a large piece of metal shrapnel had entered her right lung from the front. I suspected it had hit her aorta or one of the other main blood vessels near her heart; her face was white, her voice was weak and I could hardly feel the rapid, feeble pulse in her neck. There was nothing much I could do. We could only give basic first aid here, but I doubt if even a specialized surgical unit could have saved her. As I crouched over her trying to find a vein to set up an intravenous drip, her breathing stopped, her pulse disappeared and her frightened eyes looking at me became lifeless as she died.

We dealt with ten wounded Cambodians that afternoon and five died. I asked if there had been any Vietcong casualties to deal with. Chantrea seemed surprised at the question but said that some of them had been wounded by the personnel mines that protected the forest trails leading to the village. I asked where they were.

She paused and looked straight at me. There will be no prisoners.

Six weeks before, I had been working in the UK as a junior doctor in anaesthetics and intensive care in Reading. It was September 1980, I was 32 and tired. Junior doctors hours were very long in those days often 90 hours per week, sometimes more. The operating theatres were windowless, lit by harsh fluorescent light. In the coming winter months I would arrive in the dark and leave for home in the dark. It was all becoming stale. I felt I needed and deserved a short break.

I listlessly scanned the advertisements for appointments in the British Medical Journal but saw nothing at all that appealed to me until I glanced at an advertisement by the British Red Cross for general medical officers to go to Thailand for three months. I looked out of the window at the cold, rainy and gloomy dusk outside. I longed for some sun, warmth and fresh air and a short working holiday in Thailand was very appealing.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor»

Look at similar books to Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Memoirs of a Red Cross Doctor and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.