Amortality: The Pleasures and Perils of Living Agelessly

Charles: The Heart of a King

Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: How Gender Equality Can

Save The World!

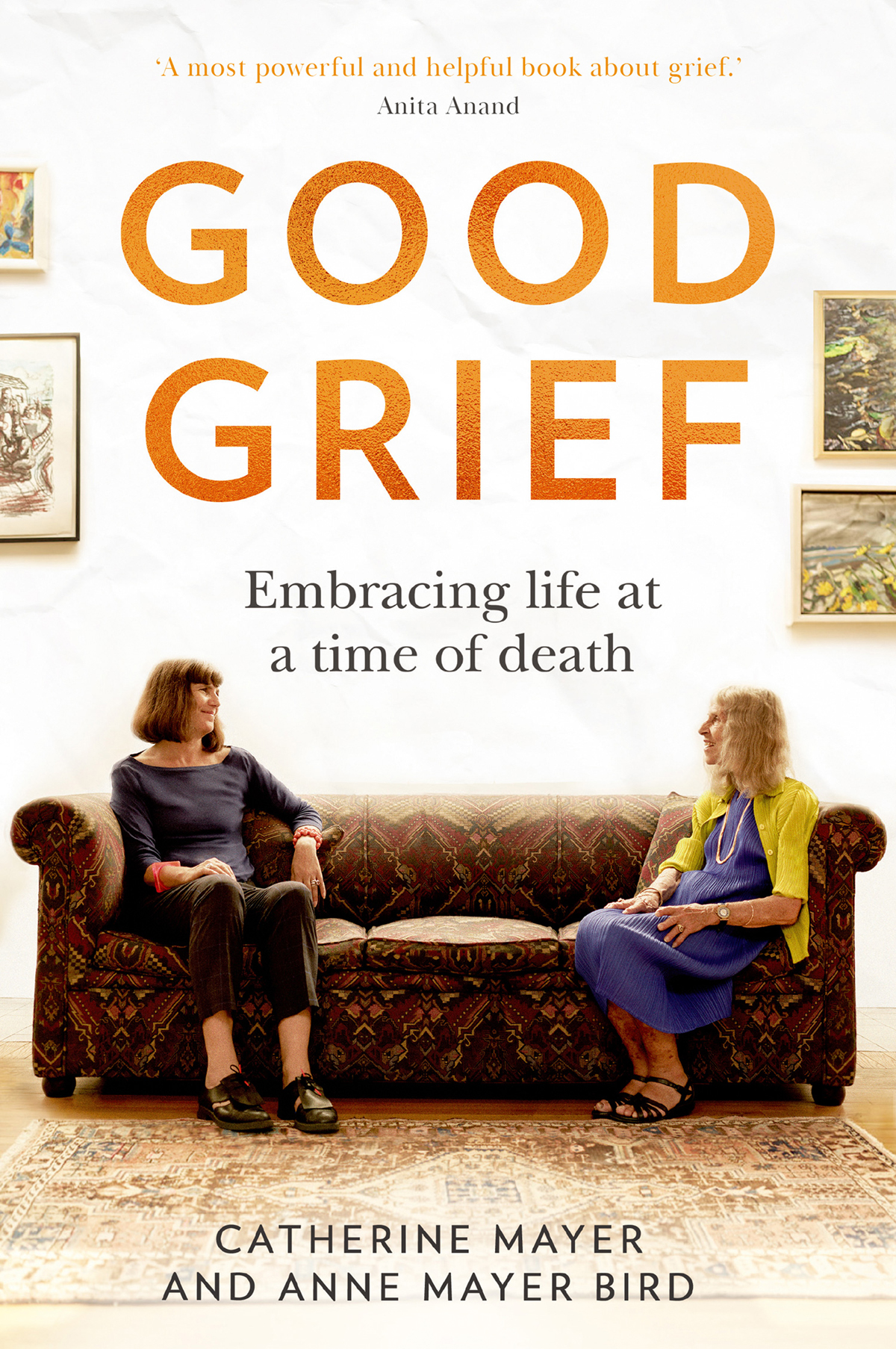

GOOD GRIEF

Embracing life at a time of death

CATHERINE MAYER AND ANNE MAYER BIRD

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2020

Copyright Catherine Mayer and Anne Mayer Bird 2020

Catherine Mayer and Anne Mayer Bird assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition December 2020 ISBN: 9780008436124

Version 2020-10-30

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008436100

To Andy and John, with our undying love

Contents

We are extraordinarily lucky, my mother and I. We have each other and we have this room.

When she and John moved to London, married just three years and still figuring out the shape of their relationship, their new home had not yet established its boundaries either. The room came later. At first the house grew warily, adding a small glass extension at the back with a slippery incline that their ginger cat treated as a slide. The local foxes chose a bigger playing field, barking and tumbling on the flat roof of the builders merchant abutting the property, a comparatively recent arrival to this estate of Victorian townhouses. The neighbourhood had seen wealthier days and would do so again. Nothing stays the same, no matter how solid it appears.

In a portent of gentrification, developers made plans to demolish the commercial unit next door and build, in its stead, a new house made to look old. My mother and stepfather debated what to do. They had more than enough space already. Yet they feared that a new neighbour, sharing a party wall, might prove noisy and, anyway, John wanted somewhere to put a piano and the art that he had started to make and collect. After five decades working in jobs he didnt much enjoy (a lifetime, he said, though it proved to be just three-fifths of his total span), he retired and began to reinvent himself as a painter. They bought the unit and knocked through the party wall, creating for themselves a garage, utility area, extra bathroom, and this, a cavernous second living room.

If truth be told and the conversations my mother and I conduct in this room often worm out truths unknown to either or both of us until the moment of utterance I never until recently warmed to this room. Its industrial proportions make it a perfect place to display paintings or throw big parties. It is less successful as a venue for intimate discussions. Two big armchairs maintain a chilly distance against the far wall, acknowledging each other only with a slight angling that directs the gaze of any occupants towards the centre of the room and, beyond that emptiness, to a Chesterfield at the opposite wall.

This is where my tiny mother usually sits, Thumbelina on the full-sized sofa, during our weekly meetings. After John died and my husband Andy stunned us by following suit forty-one days later, she and I saw each other often but at varying intervals. It was the lockdown against coronavirus, coming seven weeks after Andys death, that enforced on our timetable a form and regularity. New government rules to combat the unfolding pandemic isolated us in our fresh isolation, my mother who had never in her eighty-six years lived on her own and me, alone again after twenty-nine years of coalescence. Only when Andy had gone did I realise how much he and I resembled a sight we often stopped to admire on our weekend walks, a tree and railing merged into a single entity, the tree enfolding, the railing sustaining.

Exposed now and unsupported, I looked for fresh ways to hold myself up. The imperative to help out my mother came not as a burden, but like the small services I performed for others in those early lockdown days supplying food and medicine, posting parcels as a gift. In doing these things, I found the iron necessary to stay upright. More than that, my Sunday visits to my mother, legitimate under the rules as care work, provided the only meaningful face-to-face interactions I would have during that period, even if the lower halves of our faces were masked.

Even now it continues. Every second Sunday I change her duvet. Most weeks I fix (or try to fix) something, an iPad one visit, a recalcitrant filing cabinet the next. Every week I bring meals Ive prepared to her requests (cauliflower cheese was an early favourite; latterly weve been exploring curries). There are often other items to source too: shoes, hanging files, birthday cards. She presents me with a to-do list when I arrive she calls it an agenda and we work through it. Then, at the end of my visit, we allow ourselves to relax, she on the sofa, me in one of the safely distant chairs. And we talk.

Our starting point is usually a piece of news from the past week, whether small and personal or global and transformative. These things are anyway linked in unexpected ways. In the first months, our battles to persuade service providers to transfer household accounts into our names dragged on as the virus and furlough schemes depleted staff numbers. Automated systems failed the easiest of tests. How can I help you today, Andrew? Im Andrews widow. Andrew is dead. Oh dear, Andrew, that doesnt sound good.

For the worst part of the past year, Facebook has shown me advertisements for funeral services, as if the mischance that saw me notifying Johns friends of his death in December, organising his exequies at Golders Green Crematorium in January, Andys cremation at the same venue on Valentines Day and his memorial at the beginning of March, bespeaks a delicious new pastime. The same algorithms that take me for a funeral hobbyist decide which posts are seen by whom, which propaganda to channel to voters. They may have helped install the populist leaders in the US, Brazil and here in the UK who responded to Covid-19 not with life-saving policies but bluster and blarney.

In the big room with its gallery of paintings, the weekly meetings with my mother unfold against another, grim backdrop, both strange and horribly familiar. As the global toll of the virus rises, we cannot help but understand each death not as a statistic but a sequence of events, a body shutting down, the person there and then not there, never again there, the families distraught and numb, embarking on the same path that we already tread.