Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Advance praise for

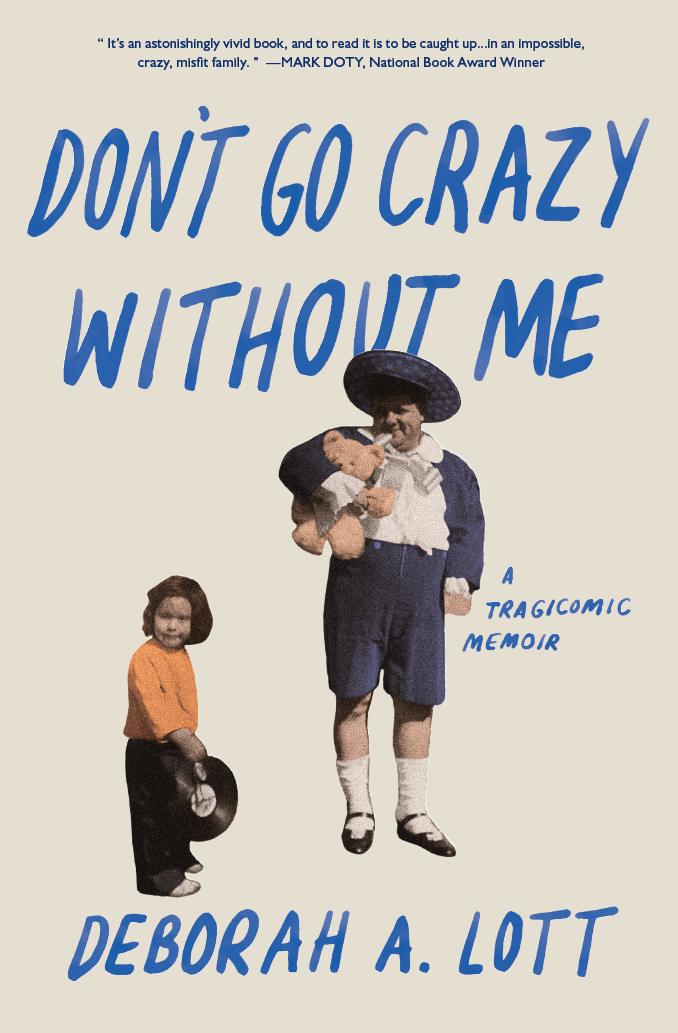

Dont Go Crazy Without Me

Deborah A. Lott writes with an intelligence thats simultaneously hilarious, devastating, and generous. Dont Go Crazy Without Me turns whatever we thought a memoir should do completely on its head and makes something glorious and fresh of the form. It reminds us why we need to laugh, especially in dark times.

PAUL LISICKY, author of The Narrow Door and Later: My Life at the Edge of the World

Sentence by sentence, Deborah A. Lott is one of the finest writers I know. Her keen insights into the dynamics of her quirky, unforgettable family, and into family dynamics in general, make this book bound to be a classic.

HOPE EDELMAN, author of Motherless Daughters

Brilliantly written with grace, generosity, and a highly refined sense of the absurd, Dont Go Crazy Without Me is the harrowing account of a chaotic, bewildering childhood. This reader was enthralled from the get-go, and Deborah A. Lott is now one of my favorite writersI kiss the hem of her garment.

ABIGAIL THOMAS, author of Safekeeping, A Three Dog Life, and What Comes Next and How to Like It

DONT GO CRAZY WITHOUT ME

a memoir

DEBORAH A. LOTT

Red Hen Press | Pasadena, CA

Red Hen Press | Pasadena, CA

Dont Go Crazy Without Me

Copyright 2020 by Deborah A. Lott

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lott, Deborah A., author.

Title: Dont go crazy without me : a memoir / Deborah A. Lott.

Description: First edition. | Pasadena, CA : Red Hen Press, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019055294 | ISBN 9781597098151 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781597098144 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: HypochondriaPatientsUnited StatesBiography. Paranoid schizophrenicsUnited StatesBiography. | HypochondriaPatientsFamily relationship.

Classification: LCC RC552.H8 L68 2020 | DDC 616.85/250092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019055294

The National Endowment for the Arts, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, the Ahmanson Foundation, the Dwight Stuart Youth Fund, the Max Factor Family Foundation, the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Foundation, the Pasadena Arts & Culture Commission and the City of Pasadena Cultural Affairs Division, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, the Audrey & Sydney Irmas Charitable Foundation, the Kinder Morgan Foundation, the Meta & George Rosenberg Foundation, the Allergan Foundation, the Riordan Foundation, Amazon Literary Partnership, and the Mara W. Breech Foundation partially support Red Hen Press.

First Edition

Published by Red Hen Press

www.redhen.org

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my fellow writers, many of whom read multiple drafts, offered unconditional moral support, and helped me write what I never thought I could bear to write: Liz Berman, Melissa Cistaro, Sam Dunn, Hope Edelman, Amy Friedman, Gretchen Henkel Clark, Monica Holloway, Mark Krewatch, Sandy Kobrin, Leslie Lehr, Danny Miller, Julia Kress Harrington, Grace Phillips, Mim Eichler Rivas, Sam Robson, Christine Schwab, Kit Stolz, and Amy Wallen.

To Karen Kasaba and Tori Morell, who read my work on a regular basis and encourage me to push it as far as I can take it.

To teachers and mentors: Karen Bender, Bernard Cooper, Mark Doty, Eloise Klein Healy, Paul Lisicky, Sharman Apt Russell, David Ulin.

To editors David Groff and Nomi Isak Kleinholtz.

To my Antioch community.

To my family for love and support and allowing me to write about them: Allan, Bob, Karen, Alison, Rebecca, Justin, Jacob, Brian, Steve and Margaret and Braz.

To everyone at RHP who has brought this book to life: Kate Gale, Mark Cull, Tobi Harper, Monica Fernandez, Natasha McClellan, Madeleine Nakamura, Caitlin Sacks, Rebeccah Sanhueza, Nicolas Nio, Amanda De Vries, and Tansica Sunkamaneevongse, and Vivian Rowe.

To Ron Spatz, founder and editor of the Alaska Quarterly Review, who published my work early on and has continued to champion it throughout the years.

To the girl who saved me in fifth grade and many times since: Linda Weed.

To Gary, whos had to relive the past with me too many times during the course of our adulthood together.

Earlier versions of some chapters appeared originally in the following journals and anthologies:

Alaska Quarterly Review, Fifteen, Trains; Bellingham Review, School Shoes; Cimarron Review, Nature Lessons; Crazyhorse, Migraine; and The Good Men Project, Robert F. Kennedy and Me.

Elephant Girl was anthologized in Open House: Writers Redefine Home, edited by Mark Doty (Graywolf Press, 2003).

Contents

PROLOGUE

Present, UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, Tuesday, 1:00 p.m.

T he three psychiatrists and I sit at the conference room table writing trauma case studies. My job, as the professional writer in the room, is to smooth out the prose, prune the jargon. Were writing about children to whom awfulsometimes unspeakablethings happened. The psychiatrists would say these case histories are factual, but I know they are stories and, like all stories, have inciting events, climaxes, and resolutions. As readers, we all long for epiphanies and revelations, redemption, and happy endings. But shift a few words or reorder paragraphs and epiphanies can evaporate, redemption erode to reveal darker currents.

As I write these childrens stories, I wonder which of them will grow up to be memoirists, compelled to put down their own versions. I also cant help but think about my own story, and all the various ways I could skew it, and what I will inevitably leave out. I cant help but wonder why I feel compelled to tell itas if I could still get it right. As if I could fix my childhood firmly in the past and not feel haunted by it. As if I could achieve clarity.

But the truth is, I dont want only clarity. I also want to slow down and relive the best glimmering moments, to wash the terror out of the bad parts, to get it all backonly better this time. To feel some kind of pure love again.

What I cant tell the psychiatrists is that down the hall from this room lies another room that holds a critical piece of my own story. Though its a clich that people go into this field because of less than idyllic upbringings of their own, these psychiatrists never talk about their own histories, at least not here, not to me. I am the one who knows she is passing.

The renowned head of the center, a brilliant, charismatic man in his sixties, leads the discussion. Strict hierarchies are observed in medicine, still largely patriarchal hierarchies. His colleagues defer to him. I try to appear as if Im deferring to all of them.

The clinicians in this room identify with the doctors in these case studiesprotagonists in these stories. I identify with the children, standing in for them with an empathy that feels a little too raw. Did you hear what the child actually said?

Red Hen Press | Pasadena, CA

Red Hen Press | Pasadena, CA