Contents

Guide

Gallery Books

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2020 by Helen Fremont

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books hardcover edition February 2020

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Davina Mock-Maniscalco

Jacket design by Regina Starace

Jacket photographs by plainpicture/Virginie Plauchut; Shutterstock

Author photograph by Mikki Ansin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fremont, Helen, author.

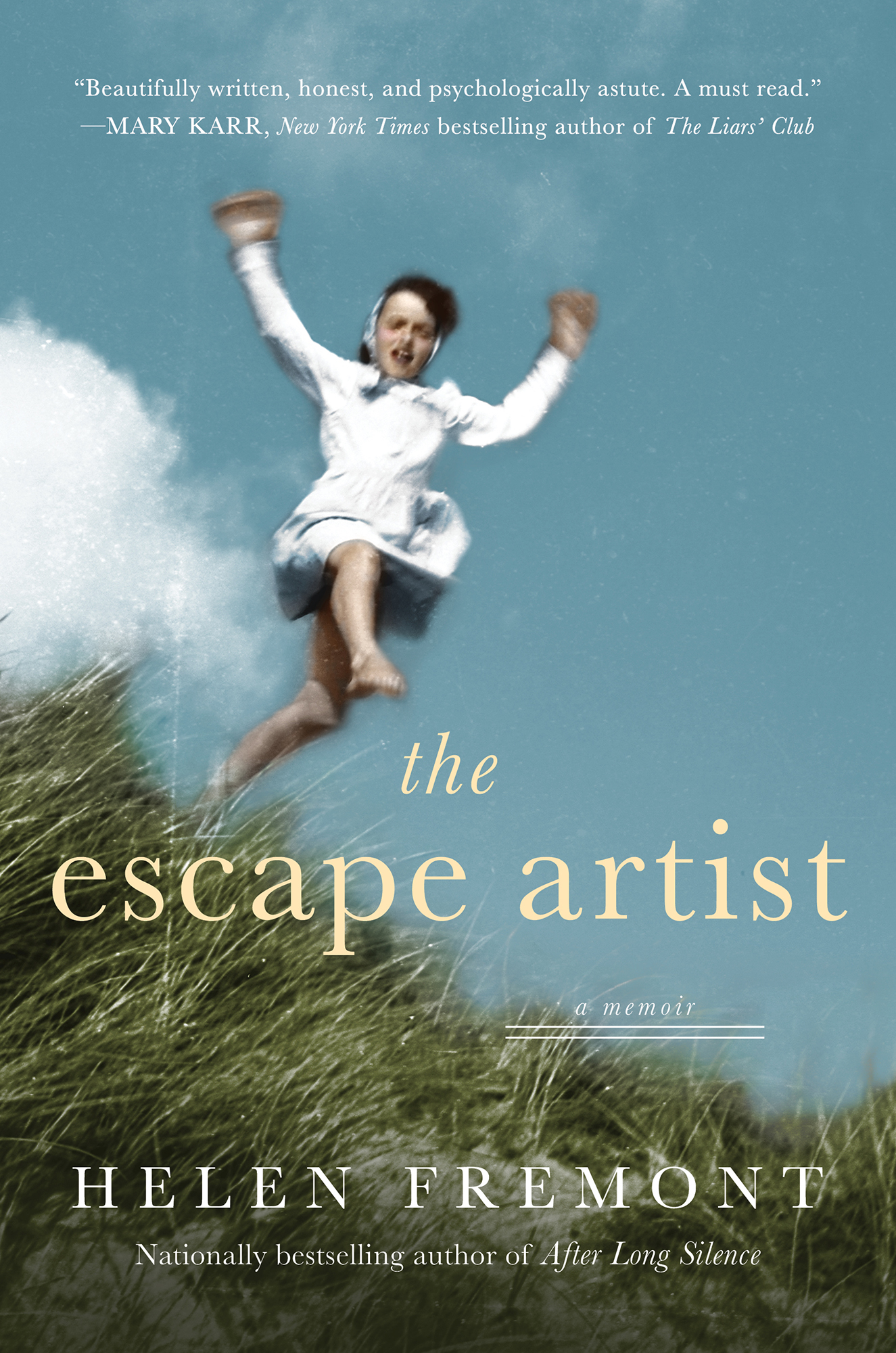

Title: The escape artist / Helen Fremont.

Description: First Gallery Books hardcover edition. | New York : Gallery Books, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019022576 (print) | LCCN 2019022577 (ebook) | ISBN 9781982113605 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982113612 (paperback) | ISBN 9781982113629 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Fremont, Helen. | Fremont, HelenFamily. | Children of Holocaust survivorsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E184.37.F74 A4 2020 (print) | LCC E184.37.F74 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/18092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022576

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022577

ISBN 978-1-9821-1360-5

ISBN 978-1-9821-1362-9 (ebook)

For Donna

authors note

T his memoir, as well as its predecessor, After Long Silence, attempts to make sense of the secrets that underlie the family in which I grew up. In both books, I have changed many names, locations, and other identifying details to provide a measure of privacy to my family and others, and to underscore that this is my story. I have been careful in making changes to select settings that are consistent with the actual events described. Because different events are considered in this volume, readers of both works will notice that I have changed the geographic setting and other details from those provided in my first volume to better maintain this consistency with the actual events described in this book.

This book also considers aspects of my relationship with my sister and our personal difficulties that did not appear in my first book. Some events recounted had already occurred; some had not. I turn to them now because I have come to understand the extent to which they inform my story.

I have relied on my journals and memories spanning decades in setting out what I have come to remember, believe, and understand about my life. Like all personal narratives, mine is inherently subjective. However intertwined my life is with the lives of others, I can only speak my own truth; I recognize that their memories may vary from mine, no matter how many experiences we share and how much I love them.

predeceased

T he light started to seep into the foothills of the Berkshires, the outline of trees barely visible against the dark sky. February 2002: I was driving the Mass Pike to Schenectady to meet with an estate lawyer. My dog, who had come along for support, sat in the backseat with his tongue hanging out, filling my rearview mirror with his blocky golden head.

Id grown up in a town near Schenectady and had driven this road hundreds of times, with its old-fashioned tollbooths and Pilgrims hats on green signs. My mother had taken me and my older sister, Lara, to Jiminy Peak on this road when I was barely old enough to hold a ski pole in a mittened fist. Shed taken us to the Clark Art Institute to gape at giant paintings of satyrs and nymphs. Later shed driven me to Williamstown to see Bertolt Brechts Mother Courage and Arturo Ui, and other plays my father refused to see because they were about war and suffering, and he had already seen too much war and suffering. Later still, Id driven the Mass Pike to college and law school in Boston. The road to the Atlantic Ocean always returned home to Schenectady, like a fishing line cast out and reeled back in, over and over.

The last time I had driven this road was in Novemberthree months beforeto attend my fathers funeral. It had seemed, at the time, a transformative reunion. My mother, sister, and I had spent hours talking, crying, laughing, and catching up, and in my little ballroom of wishful thinking, I believed we had regained our footing. But now, heading to the lawyers office, I had trouble figuring out what had really happened.

Just six weeks after Dads funeralthe letter arrived on Christmas EveI found out that I had been disowned by my family. My father had signed a last-minute codicil to his will, declaring me to have predeceased him. Id responded like a dead person: I took to my grave. I made no attempt to contact my mother or sister, and they made no attempt to contact me.

For more than forty years, our family had been closer than fused. My parents and Lara were my cell structure and membrane, my very identity. Yet so much had been hidden from meshadows and illusions that Id never understood. Id spent most of my life trying to decipher the mystery of my family, and I was still at a loss. Perhaps loss was precisely the point of our story.

When I was growing up, my mother said that our family was held together by the great glue of suffering. World War II had shattered my parents, and they had emerged from the charred remains of Europe with pieces missing. Around these holes they had built our family of four. We loved each other like starved people: we always wanted more.

A Sad and Difficult Time for All of Us

On the day I found out I was disowned, I woke before dawn as usual, slipped quietly out of bed, and stepped over my dog who lay on his side like a toppled Sphinx. I pulled on my gym shorts and T-shirt, laced up my sneakers, zipped up my parka, and went down the three flights of stairs. The streets were empty as I walked to the Y. It was the day before Christmas and the students who often made my building feel like a frat house were gone. Boston was between storms, so the sidewalks were clear, and the wind didnt hit me till I crossed Huntington Avenue. It was too early for traffic, a nice time to be out in the city, a little before 5 a.m.

I was forty-four years old and feeling optimistic: there was good reason to think that the three-year rift in my family was starting to heal. In 1999, I had published a memoir revealing my familys true identity and history. The books unexpected success proved catastrophic for my mother, and her distress, of course, wreaked havoc for the rest of us. But now, over the past six weeks since the funeral, my mother had started writing to me again, handwritten letters telling me how she was managing now that Dad had died, and hoping that we could repair our relationship. And I wrote her too, telling her about my own grief, and that I loved her, and that I was so relieved to have her back. It was not the first time my mother had cut me off, but it had been the longest and most searing of our separations, and I felt grateful and relieved and lucky and sad all at the same time. At eighty-six, my father had been suffering from Parkinsons for a dozen years. Although he and I had always been close, Moms refusal to speak to me had meant I was not permitted to see him for the last years of his life when he lived at home with her.

![Gregory Fremont-Barnes - A History of Counterinsurgency [2 volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/74652/thumbs/gregory-fremont-barnes-a-history-of.jpg)