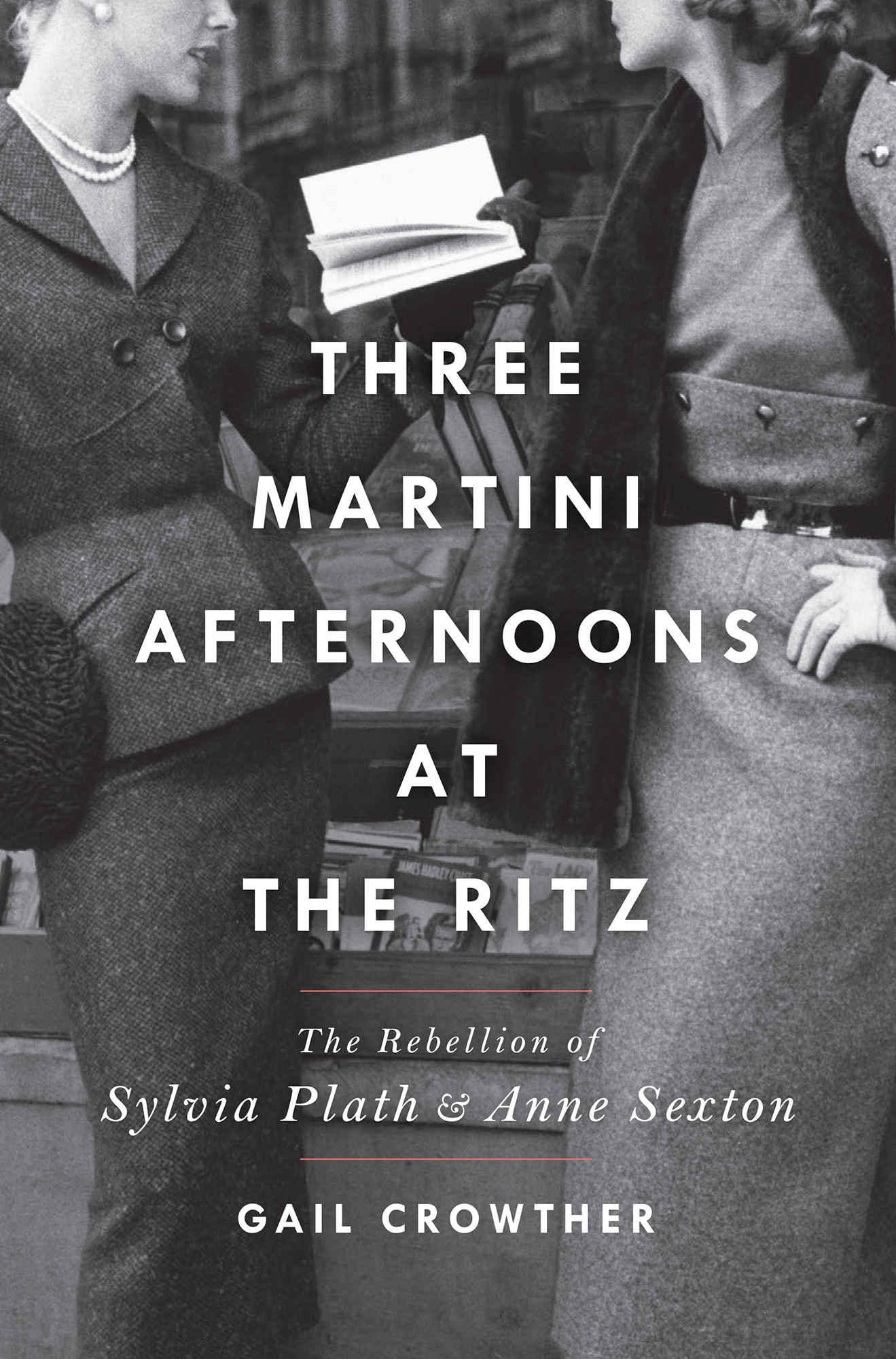

Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz

The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath & Anne Sexton

Gail Crowther

Gallery Books

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Gail Crowther

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books hardcover edition April 2021

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Michelle Marchese

Jacket design by Zoe Norvell

Front jacket photograph by Getty

Author photograph Kevin Cummins

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Crowther, Gail, author.

Title: Three-martini afternoons at the Ritz : the rebellion of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton / by Gail Crowther.

Description: First Gallery Books hardcover edition. | New York : Gallery Books, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020029091 (print) | LCCN 2020029092 (ebook) | ISBN 9781982138394 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982138424 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781982138431 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Plath, Sylvia. | Sexton, Anne, 19281974. | Women poets, American20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PS129 .C76 2021 (print) | LCC PS129 (ebook) | DDC 811/.54 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020029091

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020029092

ISBN 978-1-9821-3839-4

ISBN 978-1-9821-3843-1 (ebook)

For my parents and my sister

INTRODUCTION Kicking at the Door of Fame

I n 1950s America, women were not supposed to be ambitious.

When Sylvia Plath graduated from Smith College in 1955, her commencement speaker, Adlai Stevenson, praised the female graduates and pronounced the purpose of their education was so they could be entertaining and well-informed wives when their husbands returned home from work. The postwar ideals of domesticity, the nuclear family, and the white middle-class woman who stayed at home dominated American thought until the mid-1960s. For those with enough privilege, a womans place was ensuring that a strong family unit would mean a strong, united society. Women were respected for not pursuing their own careers or ambitions. So, they had a lot to look forward to then.

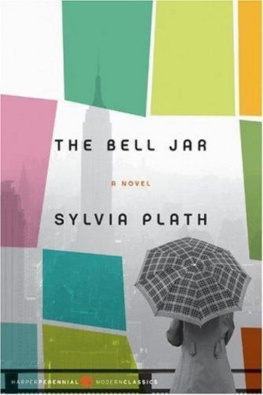

Six years after graduation, when she was writing The Bell Jar, Plath satirized this viewpoint with the memorable lines: What a man is is an arrow into the future, and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from. (Hetero)sexual liberation had its drawbacks.

In 1959, when Anne Sexton won a fellowship to study poetry under the greatly respected American poet Theodore Roethke, she wrote sarcastically to her poet friend Carolyn Kizer that he probably wouldnt like her work and shed be left sobbing in her cave of womanhood. More seriously, though, Sexton described the frustration of kicking at the door of fame that men run and own and wont give us the password for.

But in 1950s America, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton met for the first time. Both were emerging poets, and both were hugely ambitious women in a cultural moment that did not know how to deal with ambitious women. They realized that to pursue their desire to be writers would require determination, energy, and resilience. Operating in a male-dominated discipline was not easy, and their rebellion against the status quo seethed just below the surface.

Curiously, Plath and Sexton both grew up in Wellesley, a suburb of Boston, but never met during their teenage years. When their paths did finally cross, Plath was twenty-six and Sexton was thirty. Their meeting was dramatic and literary, in a writing workshop at Boston University run by the well-known poet Robert Lowell. Throughout the spring of 1959, on a Tuesday afternoon between 2 and 4 p.m., Plath and Sexton shared the same seminar space, room 222 at 236 Bay State Road. This room still exists today: tiny, with creaking wooden floors, a book-lined wall, and three airy windows offering a glimpse of the Charles River. It is a space that seems too small to have housed the personalities of Lowell, Sexton, and Plath. Sexton described it as a dismal room the shape of a shoe box. It was a bleak spot, as if it had been forgotten for years, like the spinning room in Sleeping Beautys castle. Students also observed Lowells moods and manic depression with some alarm, noticing how during certain seminars he simply seemed, in Sextons words, so gracefully insane. Insomuch as he was a brilliant poet-critic, he could be distracted and vague, and would become increasingly obsessed with the same point during his manic phases. He could lash out at students if they said the wrong thing or irritated him. One April afternoon, he was so agitated that they became convinced he was about to throw himself out the window. In fact, immediately after the class, he was admitted to McLean Hospital on the outskirts of Boston, where Plath had already been a patient and Sexton would eventually become one.

Although during these sessions Plath and Sexton tentatively circled each other, Lowell finally paired them up. Perhaps he saw a similarity that neither woman could see. Perhaps he saw thematic connections in their work. Or maybe it was just chance. Whatever it was, the two women were then connected and forced to work together, and from this point on their friendship took a different turn. Plath had a grudging respect for Sexton and was ambivalent in her praise. Her journal notes that Lowell had set me up with Ann [sic] Sexton, an honor, I suppose. Well about time. She has very good things, and they get better, though there is a lot of loose stuff.

As with all small literary circles there was competition and jealousy among the same people applying for the same prizes, fellowships, and publishing opportunities. Literary life in the cobbled streets of the Beacon Hill area of Boston brimmed with poets: Plath, Sexton, Lowell, Starbuck, Ted Hughes, Adrienne Rich, and W. S. Merwin. Plath immediately felt direct competition and rivalry over awards such as the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, an award she coveted (but much to her fury finally went to George Starbuck).

Students who audited Lowells class recalled the polar differences between Sexton and Plath, who each in her own way created an atmosphere of awe. Sexton was often late, all breezy and open, jangling with jewelry, wearing brightly printed dresses and glamorous hairstyles, and chain-smoking. According to Spivack, Sexton was a soft presence in the class, observing keenly with her green eyes behind cigarette smoke. She used her shoe as an ashtray. Her late entrances were dramatic as she stood in the doorway, dropping books and papers and cigarette stubs, while the men in the class jumped to their feet and found her a seat. Her hands shook when she read her poems aloud.