DEDICATION

To my nieces

Teresa, Sophia, and Isabel

Contents

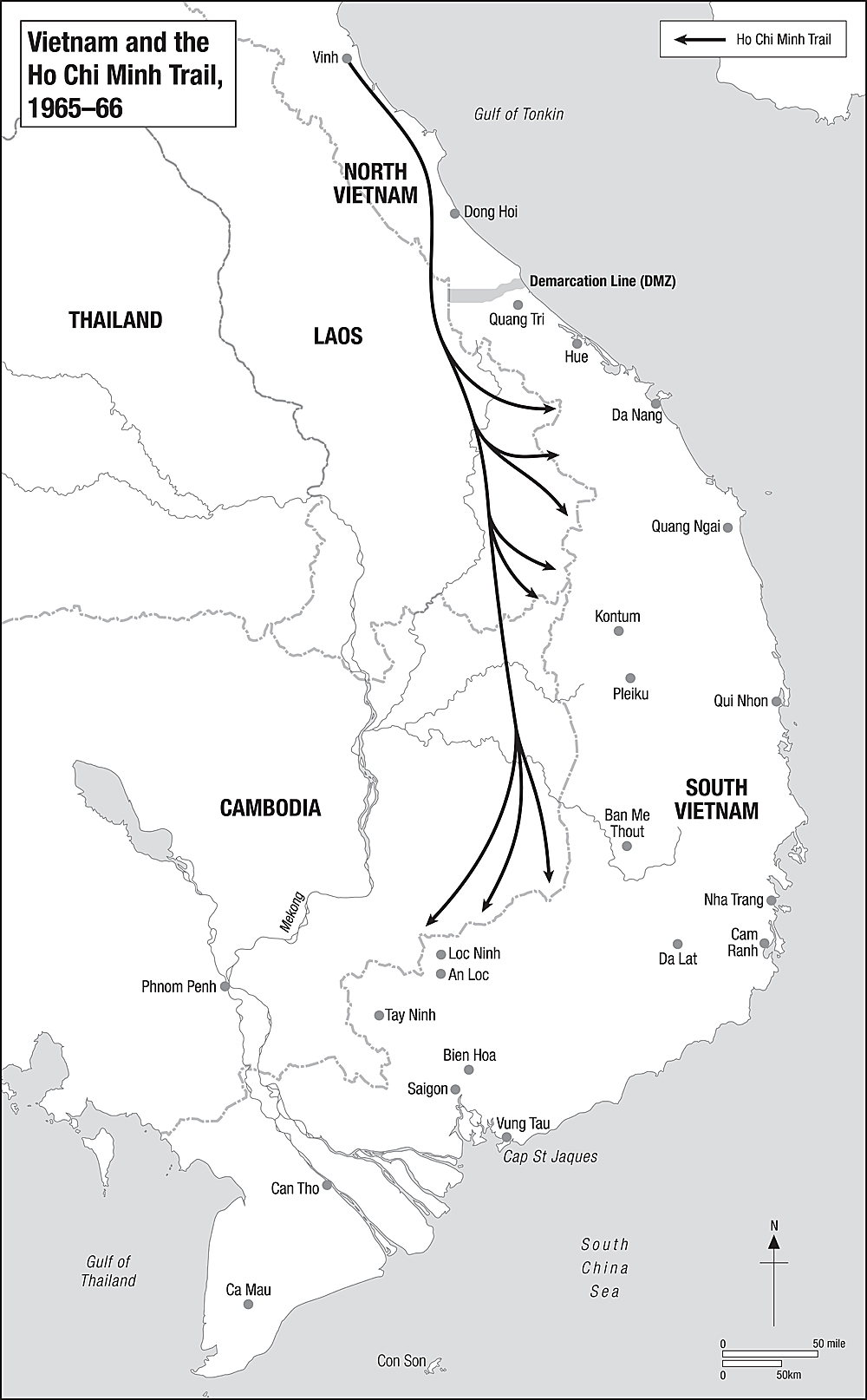

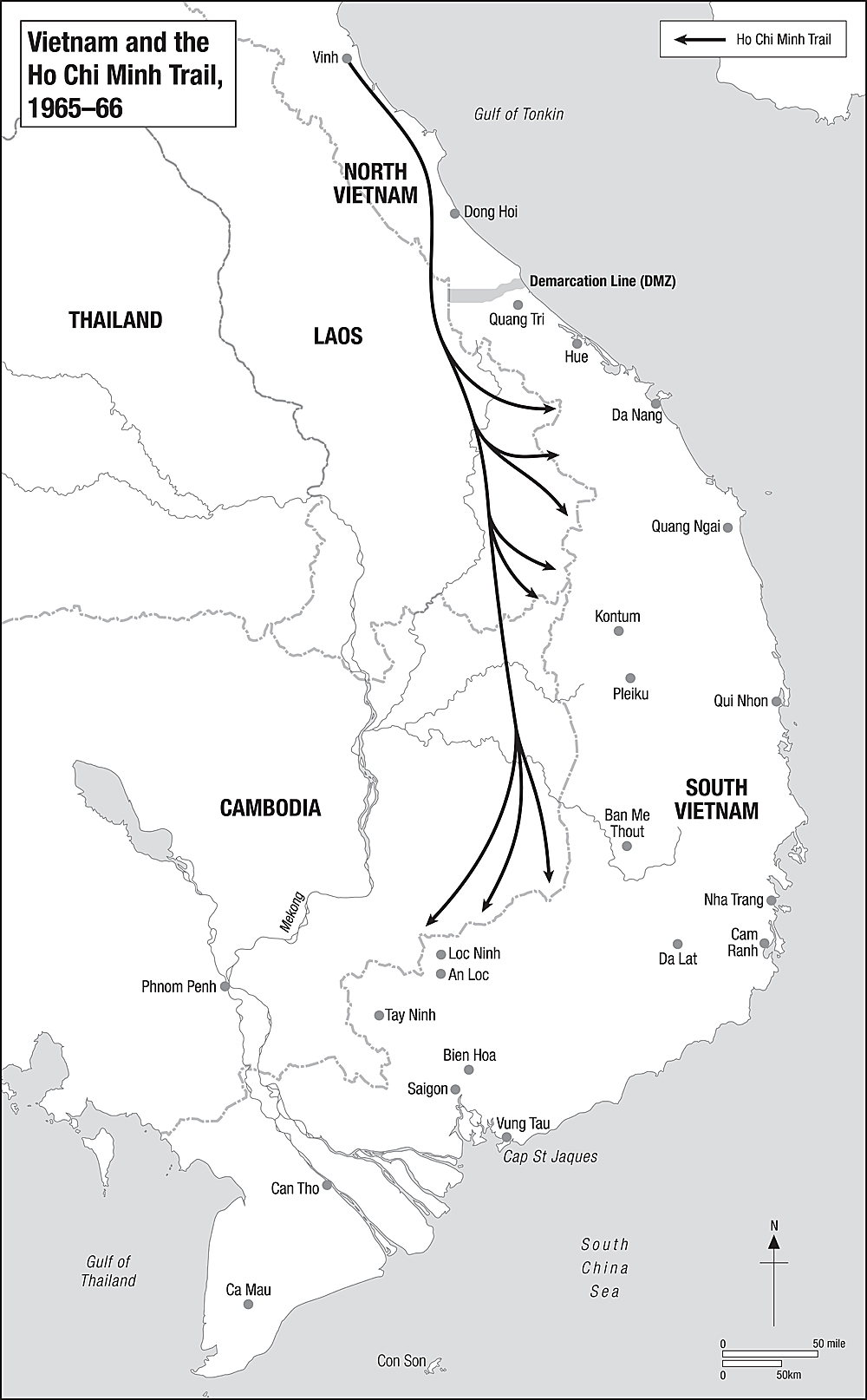

Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, 196566 |

US Corps Tactical Zones (CTZs), 196573 |

Communist Administrative Areas and Fronts |

Plei Me and the Pursuit, October 19November 6, 1965 |

Operation Cedar Falls , January 1967, D-Day and D+1 |

The Tet Offensive, FebruaryMarch 1968 |

Khe Sanh Combat Base and Unit Dispositions, January 1968 |

Lam Son 719 , February 1971 |

The Easter Offensive, MarchMay 1972 |

The Fall of Saigon, April 1975 |

A matter of days following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, a barely known Vietnamese nationalist calling himself Ho Chi Minh declared the independence of Vietnam from colonial French Indochina. The shouts from the heart that accompanied the proclamation were premature. Aided by the British, French troops returned to recover lost possessions and became embroiled in a forlorn-hope guerrilla war against the communist Viet Minh. American policy was divided. A traditional anti-colonialist stance vied with the need to support a weakened ally in the face of the Stalinist menace in Europe. But whatever doubts existed in the White House evaporated when North Korea launched its surprise attack on the South in 1950. Frances war in Indochina became an American cause against global communism.

This was the story told in volume 1 of this two-part history of the Vietnam War, In Good Faith . Four American presidents found themselves drawn deeper into a conflict underwritten by a political theory based on a barroom game: if one domino fell, all the dominoes in Southeast Asia would fall. Successive commanders posted to a newly raised Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) dangled the promise of success with more American trainers and military hardware. Kennedy fretted that America had become godparents of little Vietnam and far-seeing officials warned of a quagmire, but the promise of Camelot ended with an assassins bullet in Dallas, Texas, and by then the South had become a cockpit of squabbling, venal generals.

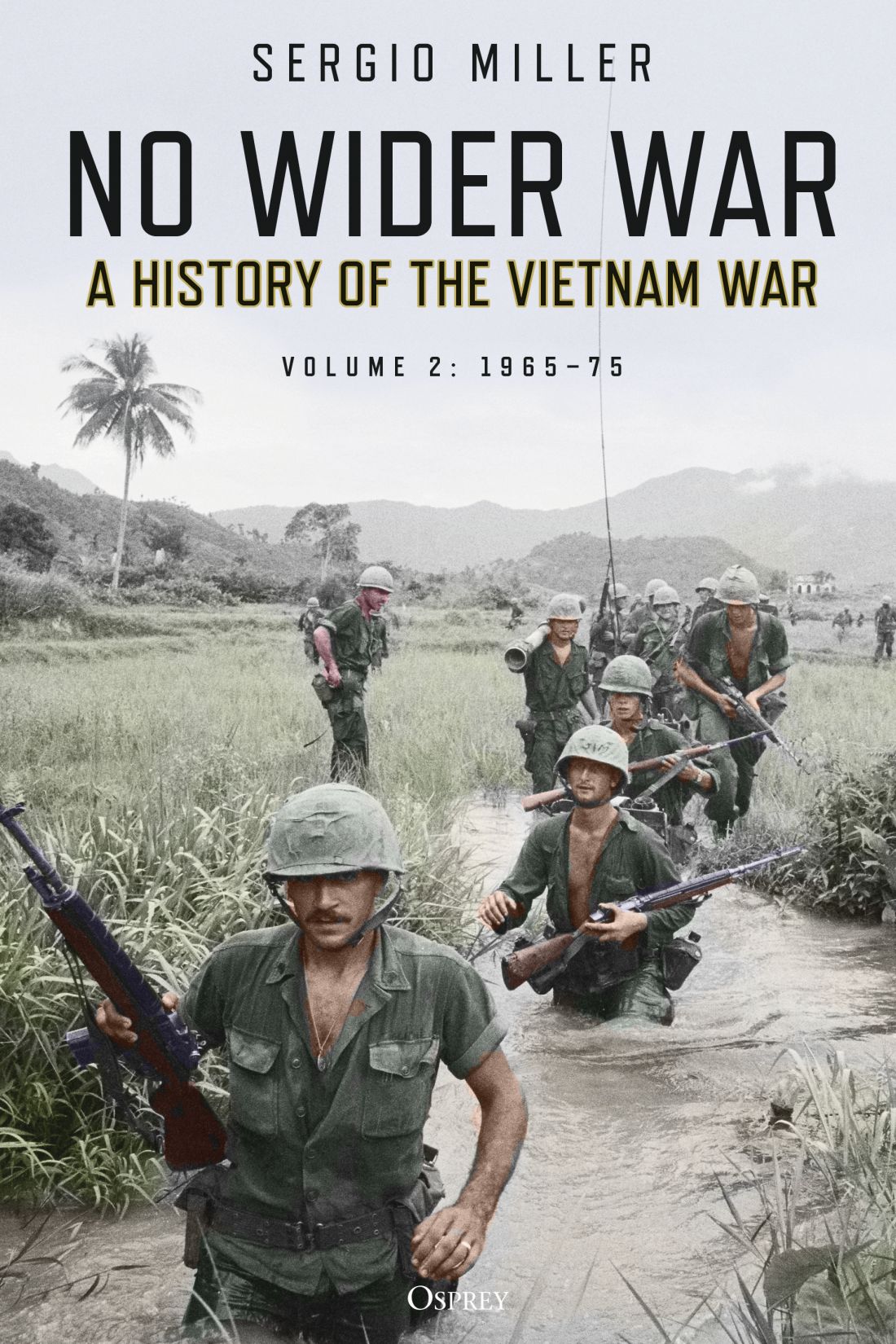

Volume 2, No Wider War , picks up the story from the deployment of the two marine battalion landing teams to Da Nang in March 1965. South Vietnam already hosted over 16,000 American servicemen, but the arrival of the marines marked the symbolic threshold after which the Souths war became Washingtons conflict. For Johnson, the agony of deciding whether to get in or get out was over, but another agony was about to unfold.

The splendid little war barely lasted the summer. No Wider War unpicks the tortuous path of escalation as one troop request inevitably led to further requests for more soldiers. The vanguard arrived with the optimism of all new boys to a war, mounting ambitious, sweeping operations. At Ia Drang American cavalrymen clashed for a first time with Hanois soldiers, leaving several hundred dead and wounded and many unanswered questions.

The numerous operations mounted from 1966 to the Tet Offensive in February 1968 can be brushed over in histories of the war, but No Wider War guides the reader through this multifaceted period of campaigning when Commander MACV General William Westmoreland sincerely believed in the possibility of winning it even though the numbers were beginning to tell a very different story. Tet, of course, changed everything, including a president, and ushered in the great double act of the war: Nixon and Kissinger.

Nixons war was memorably described as backing out of the saloon with both guns firing. By the beginning of the 1970s America had to get out of a conflict that was rending the country apart. But nobody had a monopoly on the anguish, as Kissinger eloquently put it, and Nixon was not a president willing to lose a war. Volume 2 describes how a withdrawing MACV mounted controversial incursions into Laos; backed the Souths incursion into Cambodia; and stepped up the bombing. Even as the war wound down for Americans there were still horrors to face. No Wider War candidly examines My Lai and the wider decline of a 1960s soldiery questioning the point of the war.

There was, as Kissinger wrote in the margins of a policy paper, a decent interval. But it only lasted two years. Saigons finale is vividly told in No Wider War . Washington could not undo the mistakes of three decades but the manner in which Americans made one last supreme effort to rescue South Vietnamese fleeing the communist onslaught speaks of an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

Washingtons war began in the skies, but it was in the ground war where America had to succeed, or accept the entire venture was doomed. This undertaking began where the first Portuguese explorer Antnio de Faria alighted in Indochina in 1535, and where French imperialism, fueled by the portly Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly, seized its first settlement in 1858 Da Nang. Between these two historical markers, various French, Spanish, American, and British trade missions arrived and departed. None succeeded in establishing a foothold in this harbor town, inhabited by suspicious Dai Viet (Great Viet) who spoke a dialect which has remained distinct to official Hanoi Vietnamese to this day.

The stunning bay at Da Nang, it seems, had always invited human occupation, framed by the Hai Van peninsula to the north and the scenic Monkey Mountain to the south. The earliest occupation dated to the second century AD when the region fell under the sway of the Hindu Champa (founding the original coastal settlement, Da Nak). The Champa were defeated by the Dai Viet Emperor Tran Thanh Tong at the end of the fifteenth century. It would take a further 350 years before this mysterious, and today persecuted minority culture, was finally quashed. In the early 1800s, a visiting British watercolorist depicted a small, idyllic fishing town on the later-named China Beach, one of scores of such settlements along this stretch of the coastline. The French, with imperial insensitivity, renamed the town Tourane. They eventually expanded the settlement away from the beach to the protected lee of Monkey Mountain.

The French had found a town ringed by forts, moats, and earthworks. Vietnamese resistance proved stubborn. Intermittent fighting as well as disease drained manpower. Pacification was never fully achieved beyond the immediate hinterlands. Over the succeeding decades, the better impulses of a French mission civilisatrice added the impediments of Western culture: a commissariat de la Rpublique, a chambre de commerce et dagriculture , a Blaise Pascal school, a hospital, a jardin de la ville , a neo-classical Muse Chams, and many modern conveniences. A European quarter grew with place names recalling the mother country: Rue Verdun, Quai Courbet, and the pleasant Avenue Rivire.