Table of Contents

For Leita, at long last,and for Kemp, who endured

What I want back is what I was

Before the bed, before the knife.

SYLVIA PLATH, The Eye-Mote

Acclaim for Carolyn Slaughters

Before the Knife

Searing.... Slaughter balances moments of tranquility with those of devastation, making this brave memoir engrossing.

Vogue

Two lives merge here, one of incredible beauty and one of incredible pain.... Slaughter has succeeded in penning a chilling and compelling exorcism.

Publishers Weekly

Slaughter writes with grace and psychological insight about a bygone era and the tragic circumstances of her childhood.

The Washington Post Book World

Like the best memoirsThe Liars Club, Angelas Ashes, Girl, InterruptedBefore theKnife melds the power of a true story with literary techniques.... Masterfully, she finally gives voice to the scream she describes as lodged in her throat.

Camden Courier-Post

Before the Knife is as sharp as a blade and its spare beautiful prose goes right through your heart. Rarely have I read such an honest memoir, as merciless as the blinding light of the African bush.

Francesca Marciano, author of Rules of the Wild

A classic of African writing, a book that will rank with Doris Lessings The Grass Is Singing as one of the great books about [the] subcontinent, and about the passing of a colonial era whose scares still linger.

Cape Times

Prologue

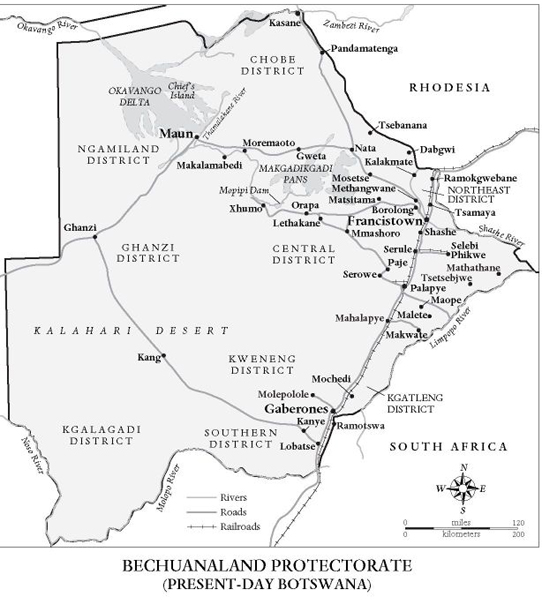

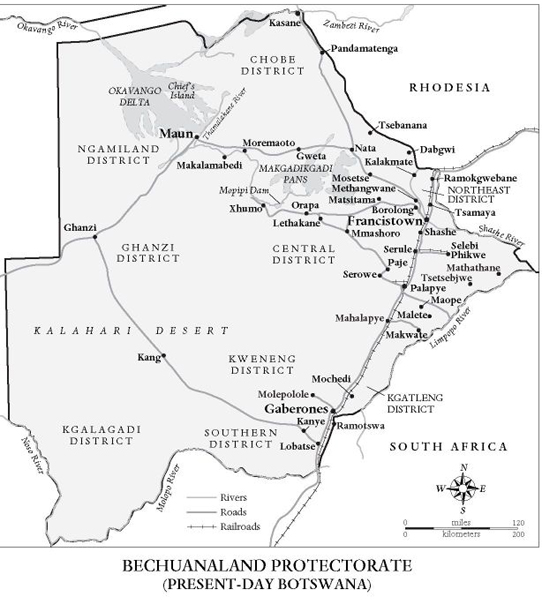

This is a memoir about my childhood in a particular part of Africa called the Kalahari Desert. Its about my mother and father and my two sisters and our lives in a singularly beautiful place, and its about the childhood I happened to have found myself in, within a family that seems, at this distance, to have been as helpless about its fate as I was about my own. What happened to me affected all of usmy mother, my father, my sisters, and me: we all fell apart under the horror of it, and we all tried to pretend that there was no horror. Each of us found our own way of surviving, and each of us got through alone. On the surface of it, we were what we appeared to be: an ordinary English family living in a very remote part of southern Africa during the lingering last years of British colonial rule. Our life was much like the lives of everyone elses around us, and we thought and behaved as the English did at that time. No one questioned our behavior, either in the country we had stolen from its natural owners, or in the quiet, secret rooms of our daily lives. And because everything was so orderly, there was nothing to point to and say, that was the moment it all began to decay.

All my life, Id believed that that moment came for me when my younger sister was born because, with her birth, my shifting and tenuous connection to my mother was broken, and we were never properly attached again. My older sister and I were sent off to boarding school and I had something of a breakdown, but as it turned out, those events were merely a small part of it, because the moment when everything changed only really came the night that my father first raped me. I was six years old. This rape, and the others that were to follow, obliterated in one moment both the innocence of my childhood and the fragile structure of our English family life. We all knew. I showed my mother all the proof she needed, and my older sister was right there in the room with me, in the bed across from mine. But once it had happened, we decided that it had never happened at all. In our privileged and protected world, we chose to bury it, we put it out of sight and memory, never said another word. This silence wasnt disturbed for decades, and though it was a silence that destroyed us, each in our own way, that isnt the story I want to tell.

When I lived in Africa, the great plains and deserts stretched as far as you could see, wild beasts roamed the vast savannas, tracing and retracing their paths across ancient migration trails, moving to and from water, decay, and death. On the grasslands and at the edges of the deserts, the black man lived and reigned as he had for all eternity: tilling his small fields, slaughtering his cattle and goats in times of plenty, starving or dying out when the rains didnt come, or when marauding tribes from over the hill brought his days to an end. Women pounded the maize, stirring black pots over wood fires that sent up small blue columns of smoke that vanished into the clear blue air. Sweet potatoes and fat speckled pumpkins hugged the brown earth, and under mimosa trees with spikes long as a childs finger, they fed their babies and shooed chickens from underfoot, waiting for their men to come back from the bush. When the sun rose in the morning, little boys shook out their limbs and led goats out to graze, trailing sticks in the sand and wandering silently through a shorn landscape dotted with thornbushes, interrupted only by a solitary acacia tree with branches laid flat across a sky as endless and blue as the sea.

But then one day, into this eternity we came marching. We sailed across the Atlantic, tall masts and white sails brilliant in the sunlight, and announced that wed discovered Africa. We took a quick look around and, picking up the four corners of the sleeping continent like a picnic cloth, we shook it up, cut it into pieces, and flung it back down in our own image. White faces radiant in the sun, we brought in our columns of mercenaries, our guns and whips; we spread our diseases and plagues, and toppled the landscape and the languid people whod lived on it since time began. We stayed on for a while, sojourning in Africa the way we had in India, never really intending to stay, dreaming always of England, and those blue remembered hills. But, for all the coming and going of white feet, the snatching of lands and lakes, and all the ivory, gem, gold, and trophy collecting, and the buildings of farms and cities, in the end it was always a short visit: white men coming to make a hurried living along the beautiful acres of the equator that stretch all the way up into the snow-peaked crests of mountains put down a few hundred million years ago. We took what we needed and packed up again, and in no time at all, the life of the white man, so transitory and scattered, so greedy and impatient, would be over: one by one, nation by nation, we pulled up and went back over the sea, and once wed gone it was as if wed never been. We left no memory of ourselves on the still air, no trace of our footsteps on the scorched plains we were goneno more than a handful of bleached bones on the lap of a continent that could remember mans first startled smile.

One

~ I was going to say that my first memory of our life in Africa was at Rileys Hotel in Maun, at the top of Botswana, on the edge of the Okavango Delta. But that isnt so. Its just that I tend to skip over the first place we lived in, as if Im still trying to forget it the way I did then. That way, for a short while, it can seem, just like the first time, somehow not to have happened at all. Old defenses rush to the rescue so that even now, whenever I think of our life in Africa, I go directly to the Kalahari. I blot out the years from three to six, when my mother and I were like the first finger and thumb of a glove that held me safely in place in the world, and gave her a measure of safety that was taken from her just as suddenly and shockingly as it was from me.

Next page