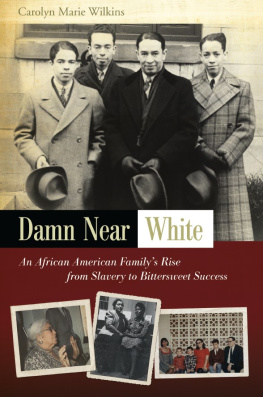

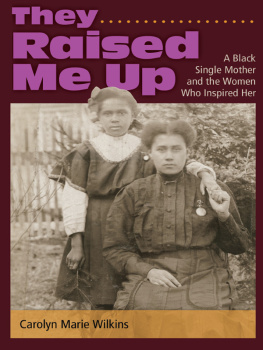

This book is dedicated to my familypast, present and future.

Acknowledgments

The Africans say that it takes a village to raise a child. In creating this book, I am fortunate to have had the assistance of my own village of supporters. Mariah Cooper persisted doggedly until she was able to uncover long-buried family secrets; Lolita Paiewonsky and Christen Enos read my early drafts and helped me find my writing voice; Mr. Clair Willcox, Sara Davis and the rest of the people at the University of Missouri Press provided invaluable editorial support.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Mrs. Laranita Dougas, Reverend Theodore Hesburgh, Judge George N. Leighton, James Montgomery, Esq., Mr. Rocco Siciliano, and Judge Anna Diggs Taylor for taking time out of their busy schedules to share their memories of J. Ernest Wilkins with me.

I would also like to thank the many librarians and archivists who helped me in my quest: Carmen Beck, Lincoln University; Robin Beck, University of Illinois; Diane Black, Tennessee State Library Archives; Frances Bristol, Archives of The United Methodist Church; Robin Charlaw, Harvard University Archives; Jean Church, Howard University; Katherine Collett, Hamilton College Library; Julia Gardner, University of Chicago Library; Fred Gillespie, Pilgrim Baptist Church; Daniel Hartwig, Yale University Archives; Michelle Kopfer, Dwight D. Eisenhower Archives; William J. Maher, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Katie McMahon, Newberry Library; Amber Miranda, Southeastern Missouri State University; Karen Roman, Travis Trokey, Farmington Public Library; Andrea Savoy, Cynthia Weidner, Sigma Pi Phi Archives; Jessie Carney Smith, Fisk University and Linda Stinson at the Department of Labor Archives.

I am grateful for the help of my Farmington friends Bill Matthews, Vonne Phillips, Bob Lewis and Faye Sitzes, and my Oxford friends Hollis Crowder and Joan Bratton at the Skipwith Historical Society, for sharing their files, research acumen and stories with me.

I'd also like to extend a warm thank-you to Dr. James Chris Wright and his family. I am especially grateful for having had the chance to correspond with Mrs. Ethel Porter before she died.

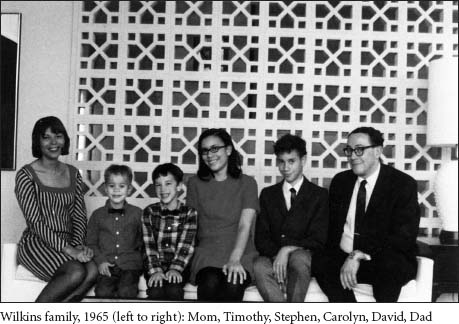

My family has been incredible. Aunt Connie and Mom patiently answered my many questions for hours on end. David, Ann Marie, Timothy, Stephen,Emelda, Sally, Jason, Rebecca and Lance each offered love, ideas, encouragement and support. My daughter Sarah's insightful comments gave me much-needed perspective, while my husband, John, stood by me every step of the way. Without his research expertise, creative input and sustaining love, the book you now hold in your hands would still be a sheaf of pages buried at the bottom of my desk drawer.

Author's Note

Some of the quotations in this book contain misspellings and other grammatical errors. In order to give the reader a feel for the characters in my story and the times in which they lived, I have chosen to reproduce these quotes, mistakes and all, exactly as they originally appeared.

Chapter One

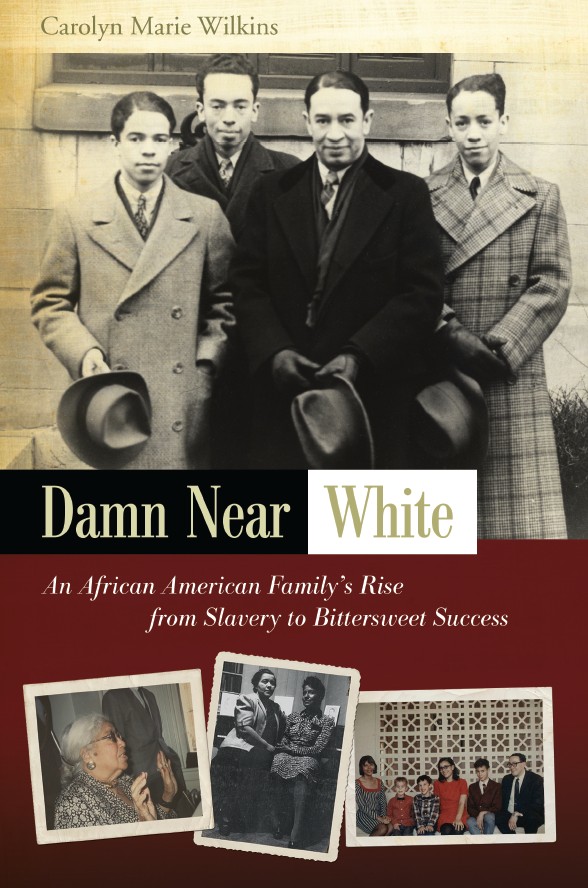

The Black Bourgeois Blues

That girl was staring at me, I could feel it from across the room. Tugging surreptitiously at the hem of my miniskirt, I pushed my way through the crowd and poured myself another drink from the makeshift bar. A second paper cupful of cheap Chianti did little to relieve my anxiety.

I didn't know a soul in the room.

It was September 1969, and I was attending my first-ever party as a college student. I had never lived away from home before, and hard as I was trying to hide it, I had never tasted an alcoholic drink before that night. More than anything, I wanted to be as cool as the other longhaired, blue-jeaned flower children who filled the small apartment.

Jefferson Airplane's music poured from a colossal speaker propped on a milk crate in the corner. Don't you want somebody to love? Don't you need somebody to love? screamed Grace Slick. Yes I did. Desperately.

Clutching my drink, I took a deep breath and headed toward the kitchen. When I turned around, the girl was standing right in front of me. She was staring even harder.

What are you? she said, inspecting me through her granny glasses.

Excuse me?

What are you? You know, what country are you from?

I'm American. I was born in Chicago.

Oh. Clearly unsatisfied, she twirled a lock of strawberry blonde hair between her fingers. You know what I mean. I mean, what ethnicity are you?

Here we go again, I thought. A familiar knot began to tighten in my gut. I looked around for someone else to talk to, but the girl had planted herself directly in my path. There was no escape.

I'm black, I replied, using the terminology of the day.

A wrinkle of irritation creased her face and twisted her thin lips into a pout.

No you're not, she said. Your skin is nowhere near black. You're more like tan. Are you Israeli?

I told you, I'm black. My mother had raised me to be polite to strangers, but this was getting ridiculous. The girl's high twangy voice reverberated across the room, and a small crowd began to gather.

I know. One of your parents must be white, then, an onlooker piped up.

You definitely don't talk like a black person, offered another voice from the back of the room.

Yeah. You don't even have a southern accent.

This was getting way out of hand.

No. I'm black. Both my parents are black. My whole family is black. Excuse me. Abandoning all hope of ever fitting in with this crowd, I pushed past my tormentors and fled into the crisp September night.

In the forty years that have passed since this incident, I have had to explain my racial background to curious strangers on a fairly regular basis. When I was growing up, my parents bypassed the Chicago public school system and placed me in an elite private academy where I studied side by side with the children of University of Chicago professors. My family lived in an integrated neighborhood, and my brothers and I played with white, black, and Asian kids as equals.

Although I now have good friends of all colors, there is no denying that much of my life has been spent straddling the racial divide. Some of the most painful rejections of my blackness have come not from whites, whose ignorance on the subject of racial identity is at least somewhat understandable, but from my fellow blacks. My first serious boyfriend was a dark-skinned black militant from the slums of North Philadelphia. He loved my yellow skin and long hair, in private, but when his friends saw us out walking in the 'hood one day, they thought I was a white girl and taunted him about it later. My boyfriend was horrified. Desperate to please him, I cut my shoulder-length hair into an Afro the very next day, but the damage had been done. He dumped me within a matter of weeks.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.