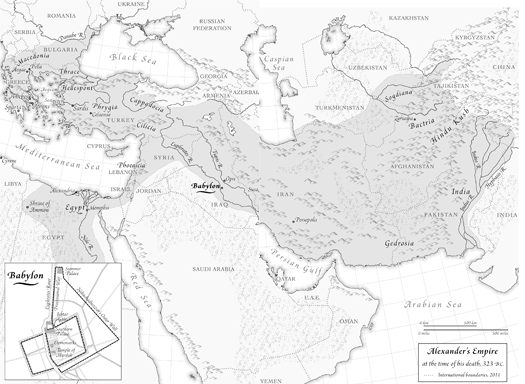

Click to view a larger image.

ALSO BY JAMES ROMM

The Landmark Arrian:

The Campaigns of Alexander (editor)

Herodotus

The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought

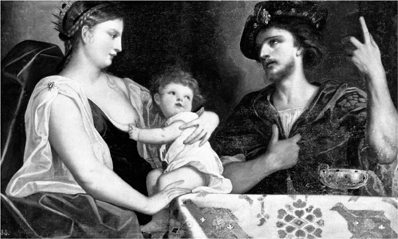

Eumenes the Greek with Alexanders widow and son ()

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by James Romm

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Romm, James S.

Ghost on the throne: the death of Alexander the Great and the war for crown and empire / by James Romm.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-70150-3

1. GreeceHistoryMacedonian Hegemony, 323281 B.C.

2. MacedoniaHistoryDiadochi, 323276 B.C.

3. Alexander, the Great, 356323 B.C.Death and burial. I. Title.

DF 235.4 R 66 2011

938.08dc22

2011008657

Front-of-jacket photograph by Tanya Marcuse | Jacket design by Jason Booher

v3.1

For my mom and stepfather,

Sydney and Victor Reed

The death of Demosthenes on Calauria and of Hyperides near Cleonae made the Athenians feel almost a passion and a longing for the days of Alexander and Philip. Just so, when Antigonus had died, and those who followed in his place had begun to inflict outrages and pains on the people, a farmer was seen digging up the ground in Phrygia. Someone asked him what he was doing. With a groan, he replied: I am looking for Antigonus.

Plutarch Phocion 29.1

Contents

Illustrations

Rhoxane and Eumenes (oil painting by Varotari, early seventeenth century). Getty Images

Alexanders Companions. Andronikos, Vergina: The Royal Tombs, Athens, 1984. 17th Ephorate of Antiquities Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Archaeological Receipts Fund

The facade of Tomb 2. Andronikos, Vergina: The Royal Tombs, Athens, 1984. 17th Ephorate of Antiquities Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Archaeological Receipts Fund

The ancient city of Babylon, digitally reconstructed. Curt-Engelhorn-Stiftung fr die Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen/FaberCourtial

Babylons Ishtar Gate. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

Macedonian infantrymen. Tsibidou-Avloniti, The Macedonian Tombs at Phoinikas and Ayios Athanasios in the Area of Thessaloniki, Athens, 2005, Plate 31. 16th Ephorate of Antiquities Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Archaeological Receipts Fund

A Babylonian clay tablet recording the death of Alexander, June 11, 323 B.C. Trustees of the British Museum

A medallion struck by Alexander depicting an Indian archer. Courtesy Frank Holt

Positions assigned to the leading generals by the Babylon settlement. Beehive Mapping

The speakers platform of the Pnyx, Athens. Wikimedia Commons/A. D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library

Movements of forces, first phase of the Hellenic War. Beehive Mapping

Southern Afghanistan, the kind of landscape that drove many Greeks to flee the East. Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Army

Demosthenes, as depicted in a Roman copy of the commemorative statue by Polyeuctus. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Alexanders funeral cart. Courtesy Stella Miller-Collett

The basic unit of the Macedonian phalanx. akg-images/Peter Connolly.

A rock carving found outside a tomb, southern Turkey. Courtesy Andrew Stewart

Athens and its harbor Piraeus. Beehive Mapping

A funerary monument, Athens. Courtesy Olga Palagia

The only known depiction of elephant warfare from Alexanders time. Courtesy Frank Holt

Movements of Antigonus and Eumenes leading up to the battle of Paraetacene. Beehive Mapping

An artists rendering of Tomb 2, Aegae. Andronikos, Vergina: The Royal Tombs, Athens, 1984. 17th Ephorate of Antiquities Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Archaeological Receipts Fund

The silver hydria containing the remains of Alexander IV. Andronikos, Vergina: The Royal Tombs, Athens, 1984. 17th Ephorate of Antiquities Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Archaeological Receipts Fund

Alexander as depicted on Ptolemys coinage, 321 B.C. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Preface

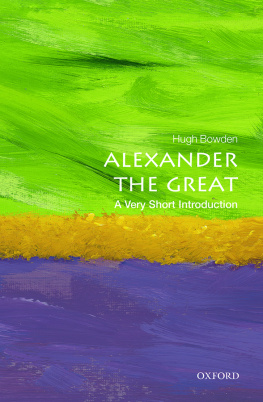

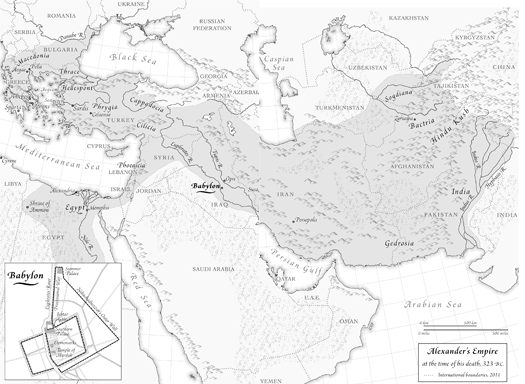

The Macedonian Empire was one of the worlds largest but, without doubt, its most ephemeral. It attained its greatest extent in 325 B.C. with Alexander the Greats invasion of the Indus valley (today eastern Pakistan), at the end of a ten-year campaign of conquest in Europe, Asia, and North Africa. But it began to collapse in 323 following Alexanders sudden and unforeseen death. It existed in a full and relatively stable form for only two years.

The story of Alexanders conquests is known to many readers, but the dramatic and consequential sequel to that story is much less well-known. It is a tale of loss that begins with the greatest loss of all, the death of the king who gave the empire its center. He died just when men most longed for him, writes Arrian, one of the ancient historians who dealt with this era, implying both that Alexanders talents were needed to keep the empire together and that the king had become an object of adoration, even worship, in the last years of his life. The era that followed came to be defined by the absence of one towering individual, just as the previous era had been defined by his presence. It was as though the sun had disappeared from the solar system; planets and moons began spinning crazily in new directions, often crashing into each other with terrifying force.

The brightest celestial bodies in this new, sunless cosmos were Alexanders top military officers, who were also in some cases his closest friends. Modern historians often refer to them as the Successors (or Argeads (members of the Macedonian royal family) who alone had the right to occupy that throne. Hence I refer to those often termed Successors simply as Alexanders generals; they were contestants for military rather than royal supremacy. Many of them would eventually occupy thrones, but only after 308 B.C. , when it became clear that the Argead era was well and truly over.

The conflicts of these generals took place across a huge swath of Alexanders empire, often with clashes occurring simultaneously on two or even three continents. I have used snapshot-like frames, starting in the third chapter, to organize disparate but interconnected events, each headed by a rubric to remind readers of the place, time, and principal characters involved. It should be noted that the dates I have used in the rubrics are contested and may differ by a year from those found elsewhere. Historians are divided over two rival schemes, the so-called high and low chronologies; the dates I have given here belong to the high chronology, endorsed most recently byrecently proposed hybrid that blends elements of the two.