Demetrius

Demetrius

Sacker of Cities

James Romm

ANCIENT LIVES

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2022 by James Romm.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in the Yale typeface designed by Matthew Carter, and Louize, designed by Matthieu Cortat, by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

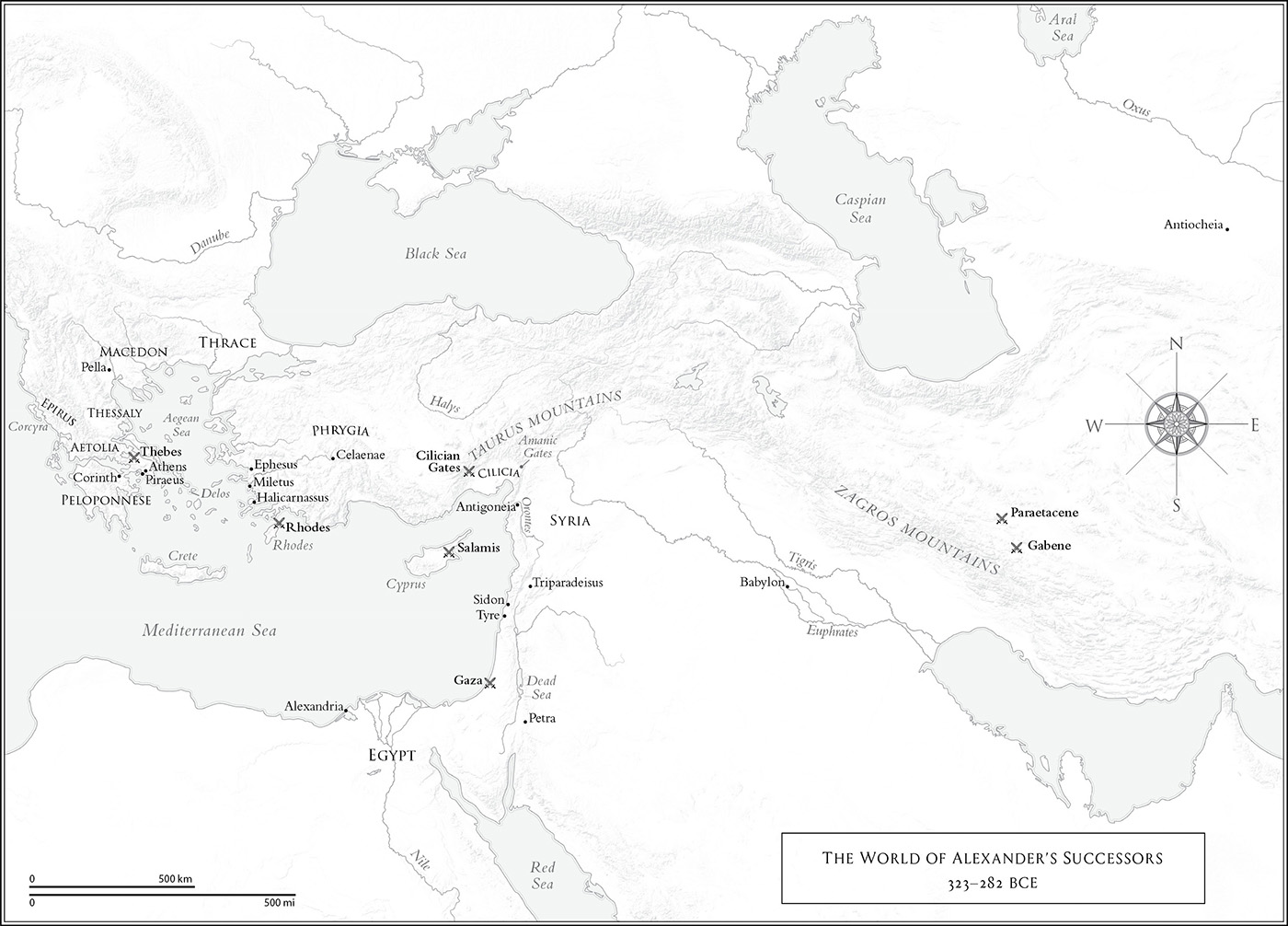

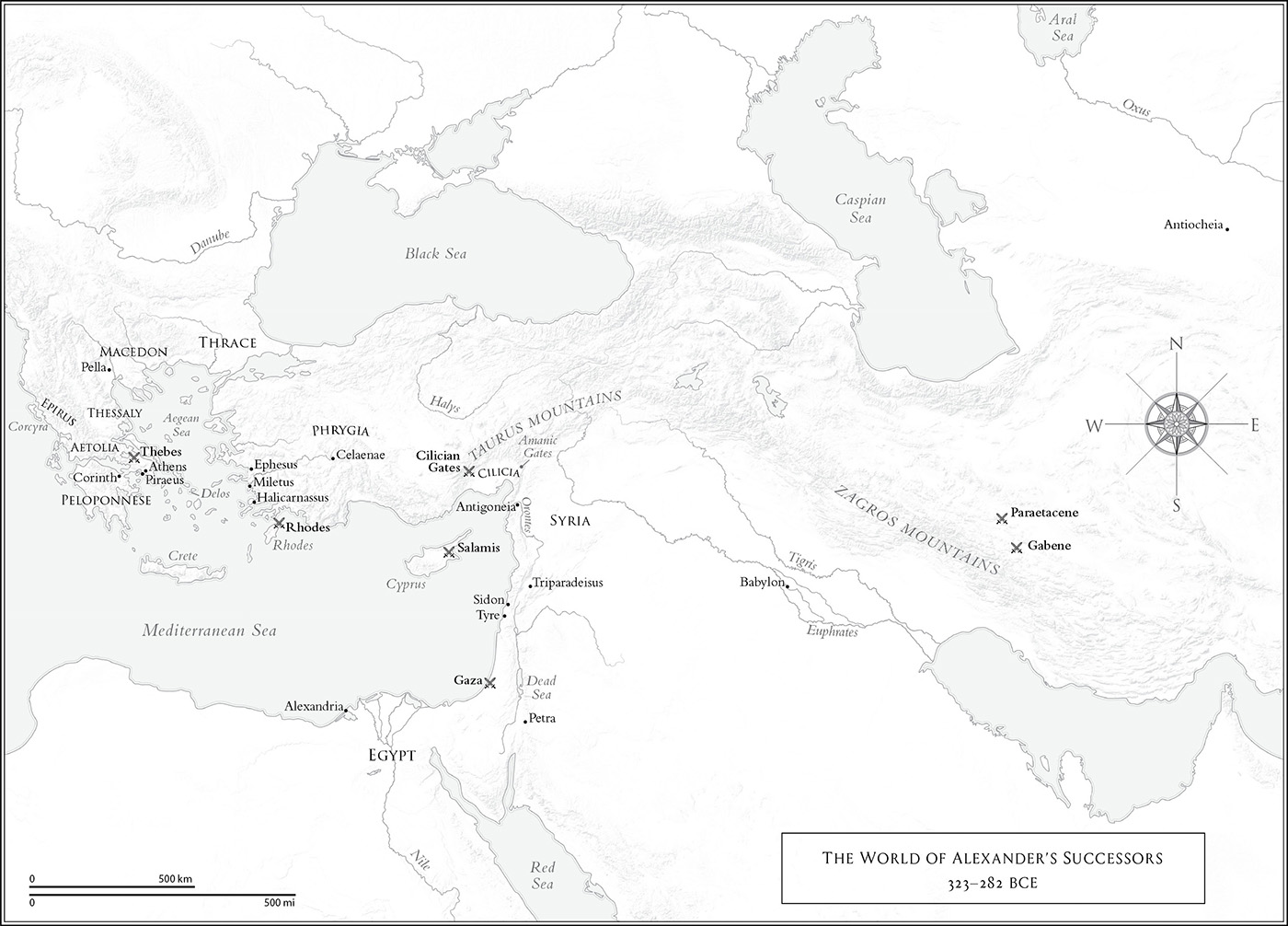

Frontispiece: Beehive Mapping.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022931846

ISBN 978-0-300-25907-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ANCIENT LIVES

Ancient Lives unfolds the stories of thinkers, writers, kings, queens, conquerors, and politicians from all parts of the ancient world. Readers will come to know these figures in fully human dimensions, complete with foibles and flaws, and will see that the issues they facedpolitical conflicts, constraints based in gender or race, tensions between the private and public selfhave changed very little over the course of millennia.

James Romm

Series Editor

Contents

Demetrius

CHAPTER ONE

His Fathers Son

On a long winter night in 322 BCE, a one-eyed man and his teenage son made their way to the coast of what is now Turkey, traveling west from a point far inland. Probably they followed the river Meander, whose winding course has given the English language a word for slow wandering. But their movements were anything but slow or indirect. They hastened toward a fleet of Athenian vessels, a convoy waiting for them at a rendezvous point. Boarding those ships under cover of dark, they set sail for Greecein secret, for their journey was made in defiance of standing orders, an act of insurrection against the ruling regime.

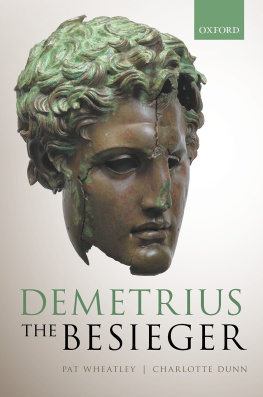

The man was Antigonus One-Eye, otherwise known as Cyclops, so named for his mangled face. He had lost an eye in his younger days, hit by artillery fire while fighting under King Philip of Macedon. A metal bolt from a crossbow-like weapon had lodged in his eye socket, but the big, bearish man had refused to withdraw or seek medical aid until after the battle was won. His son was Demetrius, by now nearly as tall as his father, but very different in looks: unscarred, smooth cheeked, and extraordinarily handsomeso much so that later in life he was followed around in the streets by gawking admirers trying to get a good look.

The lands through which the pair traveled were astir with unease and confusion. Alexander the Great had died some months earlier in Babylon, quite suddenly and without a viable heir. The empire he had ruled, stretching from modern Albania to eastern Pakistan and south to Egypttwo million square miles in extentwas up for grabs, and numerous hands seemed to ready to grab it. His empty throne had supposedly been filled, but by two kings, his son and his half-brotherthe former an infant born after his death, the latter a man in his thirties but, due to a disability, mentally unsound. Neither could exercise power of any kind, certainly not the iron-fisted control needed to hold such a vast realm together. Four regents were governing on their behalf, in a complex arrangement that seemed likely to produce discord and invite defiance.

Indeed, it was defiance that had sent Antigonus and his son westward, across the Aegean toward Greece. The chief of the four-man board, a general named Perdiccas, had ordered Antigonus to move east with a contingent of troops to support one of his close alliesa servile task and an affront to dignity. Antigonus had ignored the order, and Perdiccas, incensed, demanded that he stand trial. His demand, along with a piece of alarming news Antigonus had received, had prompted the hasty departure. Perdiccas, it had been learned, though officially just a caretaker for the two kings, was planning to marry Alexanders sister Cleopatraa move that suggested a bid for the throne on his own part.

The time had not yet come when kings could be created ex nihilo from outside the Argead family, the dynasty that had ruled Macedon from its earliest days. Strangely enough it would be Antigonus himself and his son Demetrius who would assert this prerogative, becoming, in modern terms, Antigonus I and Demetrius I, crowned heads of statethough of what state, no one was certain. But that day was as yet more than fifteen years off, after many a battle had been fought, many leaders had fallen, and the empire had fractured and split, with war zones at all of its seams. Amid that carnage, Demetrius would rise high on a surge of humanitys hopes. He would seem likeor would try to becomea new Alexander, restoring wholeness and peace to a broken world.

Perhaps Antigonus had already glimpsed that his fortunes might rest on the tall, athletic boy with exquisite features. Why else did he take his son along on this dangerous journey? His own generation, men in their sixties with bushy beards and battle-scarred faces, was quickly losing ground in the world Alexander had built. Those who now held the reins of the empire, the Babylon clan, were in their forties or even their thirties, clean-shaven after the fashion of Alexander. Smooth cheeks, flowing hair, and a melting, faraway gazethat was how Alexander was always depicted, a portrait he had carefully curated during his life. Even in death, that image held people in thrall. All who sought power over the next centuries would try to conform to the template.

Or perhaps Antigonus meant this midwinter voyage on storm-tossed seas to be an apprenticeship for his son, a lesson in autonomy and pride. If the family had been slightedas clearly it was by the orders Perdiccas issuedthen the family must seek out those who would give it respect. In Europe were men of Antigonuss stamp who shared his mistrust of Perdiccas and the Babylon regime. Chief among these were Antipater, by now nearly eighty years old, guardian of the Macedonian homeland and its Greek vassal states, and Craterus, formerly one of Alexanders officers, now working hand in glove with Antipater and married to his eldest daughter, Phila. With these two as allies, Antigonus and his son need not bow before Perdiccas or stand for his rumored marital power play.

So father and son climbed aboard an Athenian ship, accompanied by a few loyal friends and by soldiers. Their trans-Aegean voyage is the first event recorded in the life of Demetriusa fitting start to his tempestuous career. Over the next four decades, he would cross those seas many times, as the fates drove him from coast to coast and from continent to continent, tossing him down on one shore only to lift him up on another. He would never have peace, nor allow any others to have it, as the crazy zigzags of his life brought turmoil to much of the globe.

The wars of the Successorsthe men who sought to control Alexanders empirehad begun.

Perhaps the teenaged Demetrius still remembered Macedon, the land of his birth, for he spent the first years of his life there in the mid-330s. Those were years of huge change in his homeland. King Philip, father of Alexander, had transformed a small regional power into the lord of all Greece, defeating the two reigning states, Athens and Thebes, and setting up forts and garrisons to smother dissent. With an army he had equipped and trained in new tactics, with siege machines his engineers had invented, Philip had seemed capable of defeating any foe, even the Persian Empire, a massive but aging world state. Indeed he was planning an invasion of that realm when, in 336, an assassin cut him down. Alexander then came to the throne, a young man of twenty, and carried through his fathers plan to conquer the East.

Next page